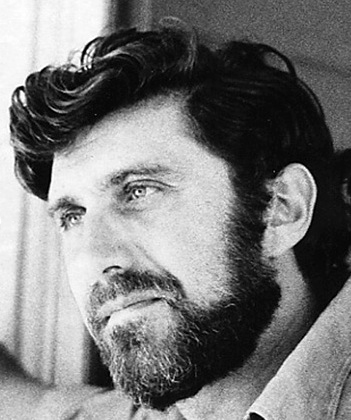

Stephen Jay Gould (credit: wikipedia.org)

There

are many who call themselves “atheists” who find my claim to believing in both

Science and God absurd. The two are incommensurable, they say.

American

writer Stephen Jay Gould who wrote on the problem of reconciling the two

domains, facts and values, called them “non-overlapping magisteria”. Two

entirely separate “domains of teaching authority”. NOMA. The name has stuck.

His

position has been widely accepted as the best that human thinkers can make of

the puzzle. We are driven by arguments from one domain in some situations, and

arguments based in the other domain at other times. We need to keep learning how

the universe works, which is what Science tells us, but then we also need

guidelines which tell us whether we should

use the powers that Science gives us and for what purposes.

Somali boy being vaccinated for polio

(credit: Andrew W. McGalliard, via Wikimedia Commons)

For

example, why do the vast majority of parents in the world today get their

children vaccinated against diseases such as measles, polio, diphtheria, etc.?

The parents make this decision because long experience has shown that vaccines

work.

Children who get vaccinated generally go on in greater numbers to more fulfilling

lives than do unvaccinated children. This is a science-based decision. Parents

who get their kids vaccinated don’t know that those kids will go on to more

complete lives. But they do know they are improving the odds for their kids by

getting them vaccinated. Similarly, to get my car repaired or my computer

cleaned of malware, I don’t seek out a fortune-teller. I go to an expert in the field.

On

the other hand, many of us are making decisions every day about the “rightness”

of actions we could take, like whether or not we should give money to homeless

people or pay more taxes to build housing for them.

Whatever

their stories, even in housing built by the taxes of their fellow citizens,

many of these people will die in a few years. They have higher rates of cancer,

heart-disease, diabetes, etc. than average citizens do. They also use drugs and

alcohol more excessively. Why don’t we just let them die and, as Scrooge says

in A Christmas Carol, get rid of the

excess population and save some money?

But

our moral reasoning tells us this policy is cruel and inhuman. If we can give

them a few more years in relative comfort, then we should do so. All the

world’s major religions exhort us to practice compassion for our fellow human

beings.

The principles underlying compassion are moral, not scientific. Science

can show us more things we could do every year, but it can’t tell us whether we

should do them. Or at least not yet.

The

problems arise when we are in situations in which we can’t decide whether to

consult the moral domain or the scientific one.

We often get very confused and anxious in these exact situations.

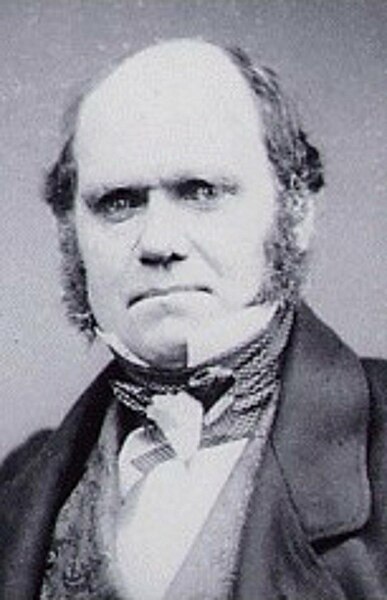

Alfred Nobel (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Should

Alfred Nobel have given his newly-discovered technology to the world? Late in his

life, he was deeply upset at the thought that he might be remembered as the merchant of death. His invention,

dynamite, was being used by hundreds of factories to make mines, shells, etc.

that were far more destructive than any that had existed prior to his time. But

his invention was already out there in the public domain, being used by arms

manufacturers all over the world. All he could do, in the end, was leave most

of his fortune to fund the Nobel Prizes. A small attempt to mitigate the

destruction that his invention was causing. Should he have thought the matter

through more carefully? Should he have kept the formula for dynamite to

himself?

Heroin

was invented in Germany in the 1870’s and it was soon being marketed to doctors

to prescribe to their patients as a safe, non-addictive substitute for morphine.

It, morphine, and cocaine were sold legally in the U.S. until 1920. It took

that long for the U.S. Congress to realize that heroin was not a safe drug. By

then, there were an estimated 200,000 heroin addicts in the U.S. Families of

addicts today can’t be blamed if they wonder whether much real research had

been done when heroin was first approved. By the time heroin had been on the

market a year to two, conscientious research would have shown it was anything

but a safe drug. Surely. But profits beckoned for the drug companies even then.

Were they greedy? Negligent? Such judgements are moral ones, not scientific

ones. Still today, drug representatives whose jobs depend on selling lots of

drugs find rationalizations that exonerate drug companies and criticize anyone

who would find the companies culpable for anything. “Let buyers beware!” they

say.

Do

investment counselors, as they call themselves these days, coax, cajole, and

badger clients into buying stocks, derivatives, or other “instruments”

(whatever that means) that are far riskier than the client has ever been told?

It seems that the answer must be “yes”. Financial crashes have been happening

since stock markets were first formed. Is the real fault in the clients who are

greedy enough to keep wanting something for nothing? Or in the brokers whom

investors are supposed to respect and trust?

When

all is running smoothly, and all clients and brokers are making money, every

person working for the system claims to be responsible for guiding his clients

to building small fortunes on which they may retire in comfort. When a crash

comes, no one is responsible for anything. No one could have foreseen what

happened on the markets. Or so the brokers and CEO’s claim. There is a

hypocrisy in this picture that stuns the mind. And yet they cry out to

authorities for more legal latitude, greater degrees of risk allowed, as they sell

and buy. When people’s pension funds, savings, and lives are ruined, is this due

to fate – like an earthquake – or is someone culpable? Again, the answer to

this question requires a moral judgement, not a scientific one.

Moral

judgements are being made by most adults even in ordinary matters every day. Do

I have a right to a gourmet coffee when my kids are all going to need new shoes

in three months or less? Should I let the driver on my right slip into the

traffic in front of me? She seems anxious to. Should I hire this man who has a

record of petty theft? Should I call that customer back and tell her she forgot

her change? We depend on moral values to guide us in such decisions. They are

not scientific.

When

I put these judgements to my atheist friends, most have little trouble in saying

that parents should get their kids vaccinated, and financiers and brokers

should have to pay out of their own fortunes to at least partly compensate

investors that the financial advisors have “advised” into financial disasters.

Nobel’s case is harder, but we’ll leave it as a problem for readers to ponder.

My

point today is that when atheists are questioned closely on why they make the moral

judgements that they do, their answers are very vague and evasive.

“Empathy is my guide” is no answer at all. We don’t give in to everyone who

looks like she/he needs our “empathy”. We don’t let our children have all the

foods they want even when they look like they’re really suffering from a lack

of candy. We don’t give convicts their freedom simply because they hate being

locked up. We don’t even let ourselves off the hook when we start to feel tired

during a run or a gym workout. Empathy, by itself, is no guide to anything.

A

complete analysis of all the reasoning for all the moral systems that have ever

been presented to the world is much beyond one blogpost. Whole libraries have

been written on the subject.

But

I can confront my atheist, and often postmodernist, friends on the matter much

more quickly than that.

If

you are sure it’s wrong to ignore the homeless, if you think the rest of us should

be doing more to ease their lives – even if some of those lives will end before

they are thirty – then you should be able to say why you think so.

On

the other hand, while we’re waiting, the people who become very evasive at this

point, who can’t really give an answer for why they believe some actions are just

“right”, perhaps deserve some further explanation from me.

I

believe in compassion, honesty, and accountability. Why I believe as I do again

takes more explanation than could ever be put into one post. But it’s in my

book (posts from April 8 to September 13 of last year) for those who are

interested. It’s a matter of doing real things to improve the odds of a vigorous,

healthy future for our descendants. That is why we try to be “good”. And we have

the values and morés we do mostly because our cultures have programmed them into

us. Thus, cultural codes must be updated. They fall out of touch with the facts

of reality every couple of generations. What we must do in this century is

learn to update our cultures without war.

But

these claims are not the point of today’s post. I have made these claims about

cultural codes and probabilities, and defended them, many times.

My

point in today’s post lies in an analysis of my atheist friends’ answer to this

simple question: why do you believe in being empathetic and responsible?

I

think this policy of being honest, compassionate, and so on reveals something embedded

very deep in the thinking of my atheist friends, something they may not care

for my revealing. But here it is.

Atheists,

if you try to live by a set of moral principles similar to the ones I have just

described, what this reveals about you is that (much as you hate the word) you have

a kind of faith. A belief in things not seen.

You

believe that when most citizens do their best to live basically decent lives,

this will lead to better results for all the citizens of your community in

years to come.

But you have not visited those years to come. And you can’t. Not

even in your dreams.

Nevertheless,

you gamble on the better effects that you think will come from you and your

neighbors practicing empathy, responsibility, and honesty.

This

faith in being good and in the healthful effects that your policy will produce –

by simple, unemotional logic – must be somewhere in you. Otherwise, your policy

and your principles would be irrational. Your actions would be no more than the

twitchings of a dying animal. What sort of rational creature would strive to

live up to these standards you are setting for yourself if she/he believed that

the principles, and the behaviors they fostered, would never make any real difference

whatsoever. That belief is the main ingredient in the mental state called “despair”.

And

many people today are suffering from depression. But many more are not. They

keep trying to be decent and hoping for the best. In short, somewhere deep inside

their thinking, they have a kind of faith. The universe works in a way that

generally gives slightly better odds to the good. All may yet be well. What is

at the core of such a belief in the general decency and sense of the universe itself?

If that is not a kind of “theism”, then what term would you prefer?

And

by the way, I believe passionately that, yes, all may yet be well. We just have

to keep working hard and being decent …and one more thing.

We

now must learn how values work, how they make us behave in some ways and

refrain from behaving in others, and how whole codes of values, which are the

key parts in what are usually called our “cultures” – how these codes evolve. Then

we may get control – all or nearly all of us – by consensus, by democratic

means – of our own cultural evolution.

And

end war. Maybe, even go on to glory.

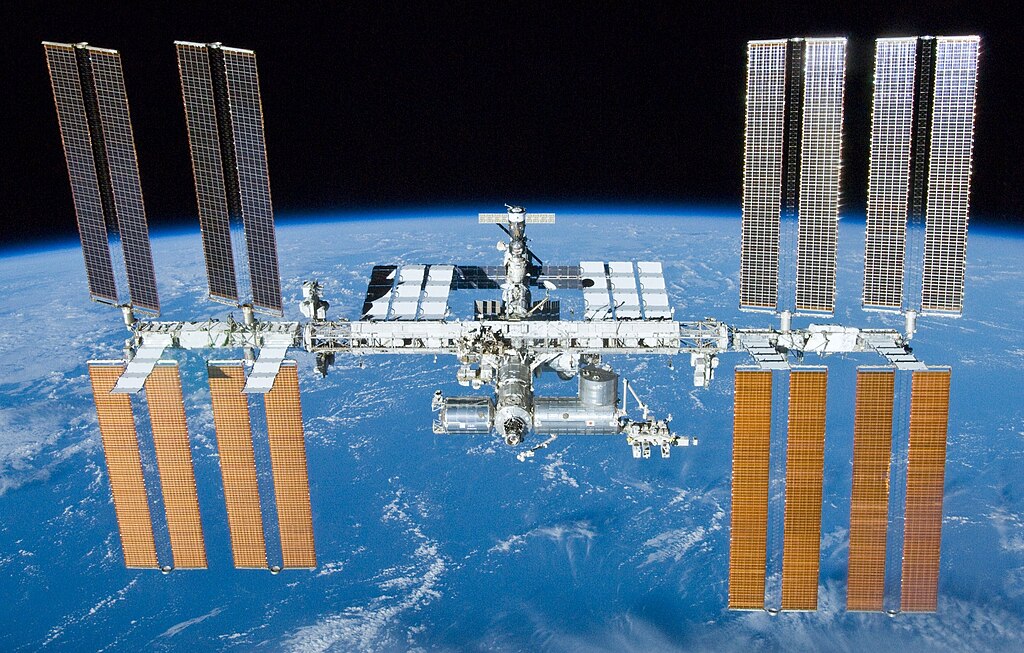

International Space Station (credit: NASA, via Wikimedia Commons)

Hard,

but not impossible. In this twenty-first century, getting easier by the day.

To

start, first, we must have a kind of faith. Life is not meaningless trivia. We

are a team. All seven billion of us. And we are meant for the stars.

In

the shadow of the mushroom cloud, nevertheless, have a hopeful day.