Michel Foucault

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Taking On Postmodernism

I

consider the way of thinking called “Postmodernism” to be a symptom of the spiritual

sickness of our time, the sickness that has left so many today filled with feelings

of dread and meaninglessness. Those feelings occur because we humans must have

a code of behavior by which to live our daily lives. To be without any code of

behavior is to be catatonic. But sadly, many of us today have come to believe

that no reliable, universal code of behavior – essentially a code of right and

wrong – exists, or ever existed, or even can exist. In fact, we don’t trust the

code by which we are running our lives right now. All codes, we have concluded,

are arbitrary and capricious. All our ideas of right and wrong are, and always were,

illusions. And so we run our lives, tentatively, under a cloud of dread.

Postmodernism

didn’t cause this ennui. It was caused by the ovens of Auschwitz and the other

horrors of the past century. Postmodernism is a response to the horror. So many

must have a code, but don’t trust the one they are living their lives by, and

thus, assume an air of fashionable skepticism: postmodernism. Unfortunately, this

numbing elixir, like a charlatan’s snake oil tonic, once it is taken, only

makes the illness worse.

How

could the disciples of tyrants like Stalin, Hitler, and their spiritual cousins

have done the atrocities that they did? That is the burning question of our

age. So far, the only answer that seems to cover all of the evidence is this

cry of pain called “Postmodernism”. It isn’t an answer. Why? Because unfortunately

for its too credulous disciples, it comes with more ailments attached than the

shaky state of health that they had before they ever heard of postmodernism.

In

the view of postmodernism, the study of history leads us to some harsh, but inescapable,

logical conclusions. History, it says, shows us that ideas of right and wrong –

values – change radically from era to era and place to place. But values are

the concepts that guide our choices and actions in our daily lives.

About

all we are able to say with confidence, the postmoderns claim, is that moral

decisions and the actions taken from them occur within a given context, and

they only makes sense within their context. In another era or place, a value

belief always seems absurd.

If

I lived in a country in which girls were routinely subjected to mutilation of

their genitals, I would be obligated, morally, to see to it that my daughters

were all “circumcised” in this way. That would be the morally right thing to do

in that context. If I had lived in the Roman Empire in Jesus’ time, I would

have been morally right to worship the emperor, attend gladiatorial games to

watch men kill each other, and own as many slaves as my means would allow.

Joan of Arc (just before her being burned at the stake)

(credit: Eugene Lenepveu, via Wikimedia Commons)

In

the Middle Ages, I would have been morally obligated to cooperate with my

neighbors to find and seize neighborhood women suspected of being witches, bind

each one to a post, pile firewood around her, light it, and burn her alive.

Moral

values vary from place to place and era to era so radically, and contradict one

another so profoundly, that the only conclusion to draw is that morals are not

based on anything universal. They are about as “right” as fashions or tastes in

shoes or perfumes. You like peppermint ice cream; I like maple walnut. You are

right in your home, and I am right in mine. So, claims postmodernism.

Is

there any system of thought that explains why values and the morés that they

give rise to change in the ways that they do? The postmoderns think they have

found one. The sad part is that the system they see is a very harsh one.

Is

there no model of all the facts about our lives, past and present, that can

reliably guide us toward our getting some kind of control over the events of our

times, so that we can steer ourselves away from the horrors humans have done to

each other in the past and worst yet, the horrors we may yet do to each other?

“Emphatically, no!” the postmoderns say.

But

postmodernism does give its disciples a role in the real world scenario, a way

of acting that is brave and even, in a very primitive way, a kind of moral: we

can, at a minimum, “tell truth to power”.

We

can learn to spot the people who are trying to convince the public of their

warped way of seeing reality – i.e., the power mongers – and we can at least

try to counter the threat that they pose. Such people always have only one

ultimate aim: to put themselves into a position that gives them more and more

power over others. Postmodernism, therefore, recommends that we learn to spot tyranny

right at its inception, and fight it, maybe even stop it, before it ever gets

rolling. We can learn to spot the potential tyrants and oligarchs by their ways

of talking, and we can confront them publicly; we can tell truth to power.

It

is worth mentioning here that we are probably not going to fight each other,

verbally or otherwise, over which flavor of ice cream to have tonight. But over

slavery, we might have some much deeper differences. Even violent ones.

I

have written at length about an alternative to postmodernism and its child, moral

relativism, but I won’t go over all that material today. Today I’ll settle for

talking about why postmodernism is incoherent even in its own terms.

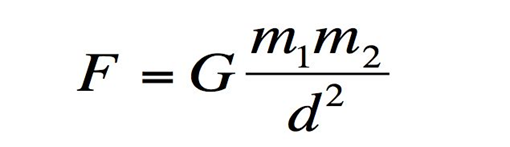

For

today, I’ll begin by saying that every system of thought has to be based on

clear definitions of a set of basic terms that all who are interested in

discussion within that system can agree upon. We have to agree on what we’re

going to talk about before we can begin to talk meaningfully about it. This is

true of Law, Anthropology, Mathematics, Medicine, or any other field we might

name.

The

prince of postmodernism, Michel Foucault, calls all the various fields that

have their own intellectual realms “discourses”. Inside of the discourse called

“Sociology”, for example, there are ways of making a case for a thesis that are

acceptable and others that are not. There are observations of the world that

count as evidence and others that don’t. The same is true of Mathematics, Law, Medicine,

History, and so on.

Unfortunately,

says Foucault, for those who aren’t familiar with a field of study, experts in

the field have already defined its basic terms and accepted rules of argument.

Armed with these weapons, they can convince credulous pilgrims who wander into

their realms that all arguments made against the experts are flawed. This is

because these experts have already cornered the field and defined the terms and

rules in ways that give them the advantage in any debate one might have with

them. They are bound to win because they have already set up the arena and the

rules of the game so that the whole contest favors them.

But

we can still give tyranny a hard run for its money, sometimes even defeat it,

if we understand how experts in any field set up their terms and rules. What is

common in all terms and rules definitions is that they are created by the use

of what Foucault calls “binaries”. Thus it is that people involved with the Law

can only define the term “crime” by contrasting it with its opposite, i.e. “a normal

act”, or in the Law’s terms, “legal” is contrasted with “illegal”. The same

thing is done with “sane” and “insane” in Psychology. In discussions about

sexuality as well, “perverse”, is contrasted with “normal”.

But

what is viewed as “normal” or “sane” varies from country to country and from

era to era, as Foucault subtly points out by writing of the genealogies, the

histories of the evolution of values in various cultures. Then, if you look

closely, you find that the people who control money, armies, courts, and police

forces always define the basic terms of their discourses in ways that enable

them to keep their power and to condemn any who might try to challenge it. Under

their own terms, carefully defined, those with the power can arrest, try,

convict, and lock up anyone who might threaten to take their power from them.

For

Foucault and his followers, the moral thing to do is to “tell truth to power”.

Confront the powerful. Explain the binaries in their discourse. Show, publicly,

that their arguments and terms amount to a rigged game for any who might try to

challenge them. Show that their terms are far more self-serving than self-evident

or logical. By these means, sometimes, one can stop them.

Postmodernism

has its attractions. It seems to bring a sort of order to the whole scattered

array of facts that history tells us about ourselves. And it lets us see

ourselves as heroes. Tell truth to power.

But

I immediately wonder what the postmodernists have to offer to replace the “rigged

games” they see in their societies, the societies into which they are born and

to which they belong, the societies in which they learned about telling truth

to power in the first place.

To

begin with, we should immediately ask whose “truth” is being told in one of

these confrontations? On what grounds does the one doing the confronting claim his

“truth” is true? And how does he know the ones he is confronting are seeking

power? What constitutes a “well-defined” term for postmodernists? Or do they

ever even recognize any terms as being well-defined?

If

Foucault and his followers even try to answer such questions, they inevitably

set themselves up as just one more power elite. They must have some terms in

place in their own discourse about discourses, or they could not make sense to

their listeners, both sympathetic and hostile. And as soon as they attempt to clarify

their own terms, they fall into circular reasoning, defining how to define.

Which will solve nothing. Then, I ask: “Who are you to be telling me anything?”

If they claim that somehow a decent person “just sees” the hypocrisy of those

who seek power, I have to ask them to define “decent”. And so it goes. We end

up with rooms, then universities, then societies full of people screaming at

each other, all claiming they are the ones telling truth to power.

Furthermore,

there are people all over the world who are uninterested in defining “decent”

or any other key term. In such cultures, answers to these queries are given

from holy texts that are already established and accepted in that culture. Experts

in those cultures say there is no need to debate any issue. One of the holy

texts will settle the matter. There are many such cultures that don’t just

differ from us in the West; they differ widely from each other as well.

Under

the postmodern gaze, if these cultures clash, as they inevitably will, how is

the dispute to be settled? Masses of people screaming at each other – which it

seems to me, various pods of postmoderns must become – are little inclined

toward compromise. We arrive, by these degrees, at a scene in which you tell

your truth, I tell mine, and then if we can’t compromise, we settle the matter

with fists or guns. It is then logical for the postmodernists to say that war

is just one more pattern of human group behavior that we must accept as

inevitable.

In

fact, under the postmodern view, why would anyone discuss anything with anyone else

ever? All discussions turn into blather and then belligerence, full of sound

and fury signifying nothing.

Even

in the West, as the last century showed us so vividly, when an old order begins

to break down, social chaos ensues, and then someone who is “strong”, namely

someone who can mesmerize and organize a lot of other people, emerges and takes

over. Hitler. Stalin. Mao. Idi Amin. And so it goes.

But

that picture does not portray how all people inevitably are. People do

communicate. They do arrive at compromises, sometimes even when they begin by

disagreeing bitterly. Some do learn to live together without constant, general

murder and mayhem. Democracy not only can work, it is working, and in many

places, getting stronger.

Therefore,

we can, in both logic and conscience, let postmodernism go. We can even resolve

to find another way of thought for these times. In fact, there are a lot of

people who are sick and tired of cynicism and despair. The Twentieth Century

was full of crimes and horrors and madness, yes. But former enemies have

reconciled. We got through it, as a species, and went on. In that fact

alone, there is much hope.

If

we are to find a better way than that of our forebears, and successfully fend

off a mushroom clouded future, postmodernism has little or nothing to offer us.

In fact, a way of thought riddled with as many contradictions as postmodernism

is can be dropped from our culture's tool kit of ideas. It doesn’t work and it won’t. Ever.

Whatever

else we may say about values, we know that in the realm of Philosophy, postmodernism

is one of the belief systems that is clearly false.