What

is this ineffable thing we are trying to grasp? Does God have a consciousness

vaguely like ours? The evidence of modern science suggests such a consciousness

would have to be as much beyond our kind of consciousness as the universe is

beyond us in size. Infinite. Trying to grasp this concept—more now, in the Age

of Science than in any previous era—strikes us numb.

The

belief is no longer trivial in more personal ways as well. If I truly believe

in the axiom on which my model of science rests—that is, the constancy of

natural laws—and also in the relevant models of reality that science has led me

to—that is, the “aware” nature of the universe and the values-driven, cultural

model of human evolution—then to maintain my claim to being rational, in my own

eyes, I must live my life in a moral way.

I must choose to act in a way that

views my own actions as rational, not as the mere wanderings of a deluded,

self-aware, absurd animal. That absurd world view, truly believed and lived, would

inevitably lead to madness or suicide.

And

the theistic view, when it is widely accepted in society, has large

implications for the activity called science. A general adherence in society to

the theistic way of thinking is what makes sub-communities of scientists doing

science possible. Consciously and individually, every scientist should value

wisdom and freedom, for reasons that are uplifting, but even more because they

are logical. Scientists know that figuring out how the events in reality work

is personally gratifying. But much more importantly, each scientist should see

that this work is done most effectively in a freely interacting community of

scientists supported within a larger democratic society.

Most

of us in the West have become emotionally attached to our belief in science. We

feel that attachment because we’ve been programmed to feel it. Tribally, we

have learned that our modern wise men—our scientists—doing research and sharing

findings with one another is helpful to the continuing survival of the human

race. Of all of the subcultures within democracy that we might point to, none

is more dependent on the basic values of democracy than is science.

Scientists

have to have courage. Courage to think in unorthodox ways, to outlast derision

and neglect, to work, sometimes for decades, with levels of determination and

dedication that people in most walks of life would find difficult to believe.

Scientists need the most sincere form of wisdom. Wisdom that counsels them to

listen to analysis and criticism from their peers without allowing egos to

become involved, and to sift through what is said for insights that may be used

to refine their methods and try again. Scientists require freedom. Freedom to

pursue truth where she leads, no matter whether the truths discovered are

startling, unpopular, or threatening to the status quo. And, finally,

scientists must practice love. Yes, love. Love that causes them to treat every

human being as an individual whose experience and thought may prove valuable to

their own.

Scientists

recognize implicitly that no single human mind can hold more than a tiny

fraction of all there is to know. They have to share and peer-review ideas,

research, and data in order to grow, individually and collectively.

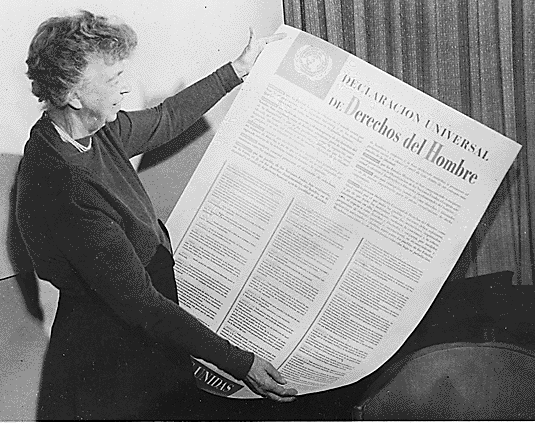

pluralistic group

at a climate change conference

Scientists

do their best work in a community of thinkers who value and

respect one another, who love one another, so much as a matter of course that

they cease to notice another person’s race, religion, sexual orientation, or

gender. Under the values-driven, cultural model of human evolution, one can

even argue that creating a social environment in which science can arise and

flourish is the goal toward which democracy has always been striving.

However,

the main implication of this complex but consistent way of thinking is more

general and profound, so let’s now to return to it.

The

universe is consistent, aware, and compassionate. Belief in each of

these qualities of reality is a choice, a separate, free choice in each case.

Modern atheists have long insisted that more evidence and weight of argument by

far exists for the first than for the second or third. My contention is that

this is no longer so. Once we see how values connect us to reality, the choice,

though it still remains a choice, becomes an existential one. It defines who we

are.

Therefore,

belief in God emerges out of an epistemological choice, the same kind of choice

we make when we choose to believe that the laws of the universe obtain.

Choosing to believe, first, in the laws of science, second, in the findings of

the various branches of science, notably the self-aware universe implied by

quantum theory, and third, in the realness of the moral values that enable

democratic living (and science itself) entails a further belief in a steadfast,

aware, and compassionate universal consciousness.

Belief

in God follows logically from my choosing a specific way of viewing this

universe and my integral role in it: the scientific way.

The

problem for stubborn atheists who refuse to make this choice is that they, like

every other human being, have to choose to believe in something. We have to

have a foundational set of beliefs in place in order to function effectively

enough to just move through the day. The Bayesian model rules all that I claim

to know. I have to gamble on some general set of axiomatic assumptions in order

to move through life. The only real question is: “What shall I gamble on?”

Reason points to the theistic gamble as being not the only choice, but the

wisest, of the epistemological choices before us.

The

best gamble, in this gambling life, is theism. Reaching that conclusion grows

out of analyzing the evidence. Following this realization up with the building

of a personal relationship with God, one that makes sense to you as it also

makes you a good, eternal friend—that, dear reader, is up to you.

* * *

And

now, to close, I would like to present a scene in a sidewalk café in Vancouver,

Canada, where two characters meet and begin a Socratic dialogue. A University

of British Columbia graduate student, Flavius, known to his friends as Flux, is

having coffee and relaxing in the spring sunshine. Serendipitously, his friend,

Evo, another grad student, strolls past. Flux recognizes him and calls out.

Flux: Evo! Evo, you subversive element! Over here!

Evo: (Drawing

near.) Well, well. The quarry you see when you don’t have a gun. What

mischief are you plotting now? Wait—I’ll get a coffee. (Goes to counter to order.)

Flux: (Muttering

to himself.) Hmm. Just the guy I wanted to see. I think.

Evo: (Approaching

with his coffee in hand and sitting.) So, what’s up?

Flux: The truth is … I’ve been getting more and

more obsessed in the last few weeks with the whole debate over the existence of

God. And over moral relativism, and whether we need to believe in God to be

good. Whether people in general do, I mean. Not you and me. We’re so good we’re

excellent. That’s an axiom. (Laughs

awkwardly.)

Evo: (Glancing

at a girl going by.) I can resist anything but temptation. But seriously,

folks.

Flux: (Looking

glum.) It is serious, actually,

this moral thing. These days, I can’t seem to think of anything else. Almost

everyone I talk to at UBC despises religion, but none of them have a way of

deciding what right and wrong are. It’s all relative, they say. Then I say they’re

committing humanity to permanent warfare, probably annihilation, when they make

remarks like that. They shrug and tell me to grow up. We’re doomed, my friend.

Humanity is doomed, even if it is a nice day. (Laughs darkly.)

Evo: Are you sure you want to start this

conversation? I have a lot to say on the subject, you know. And, after all, I’m

older and wiser than you are. (Laughs.)

Flux: Ah, be serious. You’re six months older than

I am. But … yeah, I know you’ve thought about this one. Which makes me ask—if

you’re okay with talking about it—do you still believe in God?

Evo: I do.

Flux: When we talked about this before, your

answers didn’t really work for me. But you’re saying you still believe?

Evo: Yes. (Pauses.)

I don’t buy most of the world’s religions, or priests, or holy books. But the

answer is, basically, yes.

Flux: Still.

Evo: More than ever. When did we last talk about

this stuff? At that party at the lake?

Flux: Yeah. That was it. And you haven’t changed

your mind? At all?

Evo: No. (Pauses.)

The short answer is no.

Flux: What’s the long answer?

Evo: How much time do you have?

Flux: It’s Friday afternoon. I have no place I have

to be till Monday morning. Come on. Seriously. The whole issue is weighing me

down.

Evo: Well, how about you ask questions, and I’ll

try to answer them.

Flux: All right. So do you really believe in God,

in your most private heart of hearts?

Evo: Yes.

Flux: What was the crucial moment or crucial

logical step, or whatever you call it, for you?

Evo: No one moment. No one step. No epiphanies. I

came to it gradually for a lot for reasons, backed by solid logic and evidence.

Later, it did get personal. It’s in my “heart of hearts,” as you put it. I call

my own kind of religion theism, which

isn’t a very original term. But I need to be clear that I think every person

has to work out his own way of conceiving of God and relate to that personally

in his own good time. I came to believe moral beliefs can be based on what

science is based on—the facts of empirical reality. That’s moral realism, and

it led me gradually to think we have to design a moral code that’s acceptable

for all people, and then live by it, and learn to live together. Gotta do these

things if we’re going to survive. So I got motivated to think very hard for a

while. I arrived at two conclusions. First, that moral values do name things

that are real, and second, that the core belief in the moral code that’ll

enable us to survive is theism. In other words, moral realism logically involves, or entails, theism.

Flux: All right, wait a minute. Realism? I’m not

gambling on whether my coffee is in my hand right now. It’s there, it’s real. I’m

certain of it.

Evo: No, actually—that statement isn’t a certainty,

even if you think you’re certain of it. Human senses can be fooled. That’s what

the movie The Matrix is about.

Flux: Okay. I take your point.

Evo: Every belief is a gamble, even our belief in

science and the scientific method. The smartest of smart gambles is theism.

Believing in God. Not so I can improve my odds of getting into some dimly

imagined afterlife, but so I and my kind can survive here on earth. So we can

handle what the future’s going to throw at us. Navigate the hazards. Once I

proved my version of a universal moral code to my own satisfaction, from there

it was a series of small steps to the core belief in God.

Flux: But you must have periods of doubt? Surely.

Evo: I used to. But they’ve almost gone. Mostly

because I keep answering the doubts inside my own thinking. Over and over. I’ve

seen all the doubters’ moves. I can whip ’em. (Laughs.)

Flux: So … what, then? Your belief, in your head,

your theism, is constantly fighting for its life?

Evo: Pretty much. All beliefs in all heads have to

fight to survive.

Flux: But you don’t worry that one day the theism

in your head is going to lose?

Evo: I don’t know for sure that I’ll never lose my

faith, but the signs are that it’s pretty durable.

Flux: And yet you love science?

Evo: Absolutely. Science is God’s way for us. For

humans in general, I mean.

Flux: Were you ever an atheist?

Evo: Oh, sure. I look back on it now as a phase I

had to go through. Everyone does. Some don’t ever get out to the other side,

that’s all. Other side of that atheist phase, I mean.

Flux: You don’t worry that what you see in the real

world is … only what you want to see?

Evo: I see science and the theories of science,

Flux. Testable. Replicable. They and all the experimental evidence that

supports them keep telling me, more and more, that God is there. Real.

Flux: But you did have periods of doubt?

Evo: Oh, yes. For fifteen years. And then I only

came around a few years ago to believing I ought to believe in God. That it was

a smart gamble. And that everything in life is a gamble in the end. Even the

most basic things you trust—not just science, but even believing your hands are

at the end of your arms because you see them and feel them there. Sense data—things

you sense. But for a long time, that smart theistic gamble wasn’t personal. Not

personal like you love Marie or your mom and dad. It was only cerebral. I

believed in believing in God, but I didn’t believe primally, if you get my

meaning.

Flux: Yeah, I get your meaning. So what changed?

Evo: I started meditating. Every day. Half hour or

so. Sometimes, twice a day.

Flux: Did you take a course?

Evo: Yes.

Flux: Which one?

Evo: It doesn’t matter. Check around. Find one that

works for you. Then it’ll feel like it’s yours.

Flux: That’s fair. And then what? God just arrived?

Evo: Basically, yes. I realized one day that I was

hearing an inner voice. Not a great way of putting it, but close enough. During

the time when I was trying to control every detail in my life, I was going

nuts. Then I learned to accept handling just the details my conscience—God’s

voice in my head—told me were mine to handle, my responsibility. It was like, I

became “response-able”—able to

respond—and then I got good solutions just as I was coming out of my

meditation, or right after. It was a way of thinking about God that made sense

to me. Let God—the universe, if you like—talk to me. Then I’d get some quiet,

excellent answers. Like a presence was hovering by me and nurturing me. That’s

not very dramatic. But it’s how I experience my personal sense of God. Like I

love my kids. Or my dad. Personal. First, for large, evidence-backed reasons,

and only then, second, for constant, internally felt ones.

Flux: (Studying

his friend closely.) And it still seems like a rational decision to you?

Evo: More than that, Flux. I think as a species we’re

all going to have to come to some form of moral realism, then theism, if we’re

going to get past the crises that are coming. Getting rid of nukes. Fixing the

environment. Moral realism is the only option that has any chance of working.

Nobody trusts the so-called sacred texts or the priests anymore. Most don’t

trust personal epiphanies either, no matter how intense the events feel. We

know it’s too easy to see what you want to see. First, we want models that fit

our observations of empirical evidence, over and over. And moral realism, for

me, is that kind of true. It’s a model of reality that fits the facts of

history and of daily life.

Flux: You think science proves that God exists? I

know people who’d laugh out loud at that.

Evo: They don’t see history or anthropology as

sciences, Flux. And they don’t examine the basic foundational assumptions of

science. If they did, they’d reconsider their opinions.

Flux: So tell me. For you, what are the moral

values that are grounded in empirical reality?

Evo: Humans have gradually evolved responses to

entropy, over billions of people and thousands of generations. The cultures

that emerge may vary from era to era and place to place, but every one of them

is a balance of courage and wisdom. Those values are our big-scale responses to

entropy, the “uphillness” of life. Other balanced systems of ideas and morés

built around freedom and love are our responses to quantum uncertainty. All

four values—courage, wisdom, freedom, and love—(checks them off on his fingers)—inform the software of all nations

that survive because they shape how people in a nation behave. And that

connects them to survival. And those basic qualities of adversity and

uncertainty, remember, are built into our universe right down to the atoms and

quarks. Those qualities are everywhere, all the time. We’ve learned to respond

to them, not as individuals, but as tribes, over centuries, with societies

built on those four prime values.

Flux: Those are some pretty large and vague moral

principles to build a culture around. A lot of radically different societies

could be constructed that all claimed they were brave, wise, and so on.

Evo: Which is only to say how free we are, Flux.

But notice my system is way different than saying that moral values are just

arbitrary tastes, like a preference for vanilla shakes over chocolate.

Flux: I think I see where you’re going with this

line of thought. We could build an ideal society or something pretty close to

it, couldn’t we?

Evo: We’ve been working our way toward that

realization for, arguably, two million years.

Flux: These moral values, the way you describe

them, must have been worked out over a long time, and also with a lot of pain

then, right?

Evo: Pain and more importantly, death. Which is why

we’re taught to respect values so much. Our accumulated wisdom keeps telling us

we don’t really want to revisit some of our really bad mistakes.

Flux: Here’s a mental leap coming at you. How would

the kind of ideal society you envision — brave, wise, free, tolerant — evolve,

without war or revolution? How would it resolve an internal argument over some

major social issue?

Evo: Like capital punishment, say?

Flux: Whoa! Quick answer. But, yeah. Not the one I

had in mind, but a good example, actually.

Evo: Reasoning and evidence. Gradual

consensus-building. Scientific studies. Calm persuasion. The facts say it doesn’t

work, you know. Capital punishment. I mean.

Flux: How so? It seems to me that it solves a

problem permanently.

Evo: Countries that get rid of it see their murder

rates go down, not up. It doesn’t deter potential killers. Just the opposite.

It makes them determined to leave no witnesses. To any crime. And then capital

trials drag on and on ’cause juries don’t want to make a mistake. In the end,

it costs more to execute an accused killer than to lock him up for thirty

years. Long-term studies say so.

Flux: What if he lives a really long time?

Evo: In my system, barring exceptional

circumstances, he’d still stay locked up. But most of them die in under twenty

years. They’re the kind of people who live unhealthy lifestyles. Fattening

foods. No exercise. Booze. Drugs. Cigarettes. Fights. They don’t last in prison

or out.

Flux: But even if, say for the sake of argument, they

only last twenty years in prison, that’s a long time. Guards to pay, meals,

medical supplies, entertainment … it’s gotta add up.

Evo: Not as much as killing him does by, like,

nearly three times as much. The studies say so. On average, the killers only

live about seventeen years after going into prison.

Flux: I’ll look it up when I get home. But back to

our point. You think we can solve everything by debate and compromise?

Evo: Based on reasoning and evidence, the answer is

yes. And endurance, sometimes. Just not war. The Soviet Union went from being a

seemingly unstoppable superpower to gone in my lifetime. With no global

conflict. I’ll never doubt the transformative power of endurance again.

Flux: I think I’m beginning to see your point a

bit. You see moral guidelines as being grounded in the physical facts of

reality?

Evo: I’ve made that case for myself and some others

many times over. Entropy and quantum uncertainty are built into the fabric of

reality. As long as I’m in a universe that is hard and scary, then courage,

wisdom, freedom, and love will be virtues. That picture—for me, anyway—is more

reliable than my senses. It’s eternal. I’m 99.999 percent sure.

Flux: And that proves for you that God exists?

Evo: That and a couple of other main points. Even

assuming the universe stays consistent from place to place and era to era is an

act of faith. No one can prove the future will go like the past. But we take it

as a given that the universe has that kind of consistency. Science wouldn’t

make any sense under any other first assumption. Then, I get direction from

today’s cutting-edge science—quantum physics. All the particles in the universe

are what physicists call entangled,

you know. Which just means that the universe has its own kind of awareness.

Flux: What, like I’m aware?

Evo: As far beyond your and my awareness as the

universe is beyond us in size. Yeah, that’s a hell of a statement. I know full

well what I’m saying. But look at the evidence. Let me say it all at once, as

plainly as I can. The first step to theism is believing in the consistency of

the universe. The second is believing in the awareness of the universe. The

third is moral realism, which means believing that courage, wisdom, freedom,

and brotherly love—the Greek word agape—steer

us into harmony with the particles of matter, from quarks to quasars. Those

three big beliefs—in universal constancy, universal awareness, and universal

moral truth—when they’re added together, tell me this universe is a single,

aware, caring entity. This aware universe is “God,” if you like that term. If

not, that’s okay. Call it by whatever name works for you.

Flux: Cold sort of caring, don’t you think? There

are a lot of cruel things in life.

Evo: No, it just looks that way to us sometimes.

But it’s unreasonable and unfair for me to ask God to pardon me from getting

cancer or meningitis or whatever if the dice roll that way. God loves it all,

all the time. God loves the avalanche that buries the careless skier who skis

out of bounds. God loves malignant cells and meningococcal bacteria just as

much as God loves me. We may learn how to change the odds, to cure meningitis

or prevent cancer, but in a universe that is balanced and free, those

scientific advances are up to us. Our brains evolved to solve puzzles exactly

like those ones.

Flux: You know there are people who get the

consistency-of-the-laws-of-science assumption, even the quantum-entanglement-awareness

one, but leave you right at that moral realism step.

Evo: Oh, I know. They keep trying to find some

other way to extract principles of good and bad from the natural world. A lot

of people don’t want God. They want to be in charge. (Laughs.)

Flux: Other species—chimps, squirrels, and so on—find

altruism on their own, you know. Sometimes, one of them will do something for

the good of the community and get killed because of it.

Evo: Then the next thing to ask is: What kind of a

universe rewards those animals’ finding and practicing altruism? People finding

altruism in nature and saying that means they don’t need to believe in God in

order to be decent …that dodge is no dodge at all. It only delays answering the

moral question. Why is being altruistic – what they call “good” – a desirable

way to be? So the tribe survives? Well, if that’s the case, then we have to ask

again: what is that telling us about the basic nature of reality?

Flux: All right, I see why you say that. Your moral

values would seem moral to aliens in other worlds. Do you dislike people who

keep, as you say, “dodging” the moral realism question?

Evo: Not at all. As long as I can see that they’re

trying to live lives of courage, wisdom, freedom, and love, I love them. They

may get old and die and never say that they believe in anything like God, but I

don’t care a bit. I still love them. Hey, if they try hard to live decent

lives, for me that’s enough. But believe in God? By the evidence that shows on

the outside of them—which, by the way, is all science cares about—they actually

do. Do believe, I mean. They just sentence themselves to a lonely existence

inside. Which is their choice, of course. But I still love them.

Flux: They’d tell you that viewpoint is pretty

condescending.

Evo: They have, many times. It’s still okay. We can

live together in peace. And still make progress and survive. That’s all that

really matters. (Pauses.) But we must

choose to live. Surviving’s not a given. So we need a system of ethics in order

just to decide even simple things, minute by minute, day in and day out, about

every object and event we meet up with. Good or bad? Important or trivial? Take

action or not? What are my action choices? Which one looks like the best gamble

in this situation? The most efficient

moral code will be the one that’s laid out so our decisions are quick,

efficient, and accurate. Consistent with the facts, short and long term. A

central organizing concept—a belief in God – is just efficient. At least to

start with. It’s only after a lot of work in yourself that it becomes personal.

But it’s first of all just … efficient. It gets results.

Flux: Your picture isn’t very comforting, you know,

Evo. The mental space it offers is pretty bare.

Evo: I know, I know. I’d be a liar if I offered you

easy grace. You first have to choose to be responsible for your own life. Then

so many other challenges come. But they’d come anyway. It’s just that if you

choose to bow your head and take the beatings fate dishes out, without trying

to figure things out and improve your odds of happiness, your life will be even

worse. You have to choose to choose, and even then life is going to be rough.

God’s a hard case. But I’m okay with seeing God as a pretty hard case. To make

something out of nothing, he has to be. A balance of forces makes something out

of nothing. And in that picture, God made us free, Flux. Whether we choose to

rise to the challenge, to live bravely and creatively, is up to us. Out of the

labor, we make ourselves – and then our society – good, and if we’re really

good, we teach our kids to do the same. Hopefully, even better.

Flux: You don’t believe in miracles, do you?

Evo: “Only in a way” would be my answer there. I

think events that look miraculous happen. Things that look like exceptions to

the laws of science. But later they turn out to have scientific explanations.

For me, everything I see around me all the time is the miracle. What’s it doing

here? Why isn’t there just nothing? And then the living things in the world are

much more miraculous, and then … a baby’s smile … you know what they say. It

doesn’t get any better than that.

Flux: Is there a church you could belong to? Are

you pulled to any of them?

Evo: Unitarians, maybe? Nah, that’s another

question that you need to answer for yourself.

Flux: Any you hate?

Evo: Honestly? Nearly all of them. Priests make up

mumbo-jumbo to take away people’s ability to think for themselves. It’s easy

with most people because they want security. But there’s no such thing. Not in

this lifetime. That one I’m sure of. Maybe they don’t consciously make it up,

but they do make it up. The priests, I mean. It gets them a slack lifestyle so

they gravitate to rationalizing ways to protect that. Over generations, the

lies just keep getting worse. No, I’m not big on organized religion.

Flux: Would you call yourself a dreamer? A

starry-eyed optimist?

Evo: I seem that way to some people, I’m sure. My

view of myself is that I look at the long haul. I’m most interested in that.

Then, what energy I have left over I can give to the small, confusing ups and

downs of everyday matters. I guess some would call me a dreamer. But cynics are

cowards to me. It’s the dreamers who have courage. And once in a while they

turn out to be right, you know. (Laughs.)

Flux: I better let you go, Evo. I’ve kept you long

enough. I was just feeling … down … you know.

Evo: You’re not keeping me from anything that

matters as much as this talk does, bro.

Flux: Alright. I’ll take that as being sincere.

Actually, knowing you as long as I have, I know it is. Thank you. I’m feeling …

I don’t know … hopeful, somehow, right now. (Pauses.) Actually … I think I get it.

Evo: Welcome home, Flavius, my friend. Welcome

home.

Here the Great River Now

empties into the sea;

Here the babbles and

roars of Duality cease;

Every echoing gorge,

every swirling façade,

Is dissolved in the infinite

ocean of God.

(Author unknown)

Notes

1.

Nicholas Maxwell, Is Science Neurotic? (London,

UK: Imperial College Press, 2004).

2. “History of

Science in Early Cultures,” Wikipedia,

the Free Encyclopedia.

Accessed May 2, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_in_early_cultures.

4. “Pawnee

Mythology,” Wikipedia,

the Free Encyclopedia.

Accessed May 2, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pawnee_mythology.

5. “Quantum

Entanglement,” Wikipedia,

the Free Encyclopedia.

Accessed May 2, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_entanglement.

6.

Jonathan Allday, Quantum Reality: Theory

and Philosophy (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2009), p. 376.

7. “Quantum

Flapdoodle,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May 2, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_mysticism#.22Quantum_flapdoodle.22.

8. “Occam’s

Razor,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Accessed May 4, 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor.