Photo of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863

In the United States, the idealism of the American version of the

Romantic revolt attempted to integrate the Enlightenment ideals of reason and

order and the superiority of these Western ways with Romantic ideals that

asserted the value of the individual. This produced painful excesses: genocide

of the native people, enslavement of millions of Africans, and, one of history’s

worst horrors, the US Civil War.

America had to undergo some difficult adjustments before it began

to integrate the Christian belief in the worth of every individual with the respect

for the law that enables individuals to live together in peace. But the slaves

were freed, and the government began to compensate the native tribes (with

reserves of land and with cash) and take them into the American mainstream

(with opportunities for Western-style educations), or rather, to be more accurate,

Americans began moving toward these ideals with more determination, and they continue

to do so into this era. A very slow process, but we must not give up.

Thus, in the larger picture of all of these events, the upheaval

called the Romantic Age wrote into the Western value system a greater

willingness to compromise and a deeper respect for the ways of compromise, resulting

in the institutions of democracy. These guided people toward balance and so kept

their various countries from devolving into chaos. Democracy was, and is, our

best hope for creating institutions by which people use reason and debate

instead of war to find a timely balance in each new generation between the

security-loving conservatism of the establishment and the heated passions of

the reformers.

Lesser sideshows in the swirls of history happen. These are

analogous to similar sideshows that have happened in the biological history of

this planet. Species and subspecies meet, compete, mingle, and then thrive or

die off. But the largest trends are still clearly discernible. The dinosaurs are

long gone, and so it also goes in human history. A viable new species of

society keeps emerging in what can properly be called a synthesis. In a

compromise, two opposing parties each give a bit of what they like in order to

get a bit more of what they want. What happened at the end of the Romantic

upheaval was like what Hegel called a synthesis, a melding between a thesis and

its antithesis, but it was also something more. As conditions changed and old cultural ways became obsolete, the

synthesis that arose was a new species of society: modern representative democracy.

A new life form, vibrant and unique.

Occupy Wall Street protesters, New York, 2011

The idea of democracy evolved until it saw the protecting of the

rights of every individual citizen as the most important reason for its

existence. All of this came about from the melding of Christian respect for the

value of every single human being, Roman respect for order and discipline, and

Greek love of the abstract and of the seer who can question the forces that be,

even those of the material world. Representative democracy based on universal

suffrage was the logical goal of the Renaissance and Enlightenment world views

when they were applied by human societies to themselves. The Romantic Age simply

showed that the adjusting and fine-tuning takes a while. And it continues on.

In

the meantime, what of the Enlightenment world view? Inside the realm of science,

the Enlightenment was still entirely in place and, in fact, was getting stronger.

The Romantic revolt left it untouched, even invigorated. Science came to be

envisioned, by scientists, as the best way to fix the ills of society.

Under

the scientific world view, as both Newton and French scholar Pierre-Simon

Laplace had said, all events were to be seen as results of previous events that

had been their causes, and every single event and object became, in an

inescapable way, like a link in a chain that went back to the start of the universe.

The giant universal machine was ticking down in an almost mechanical way, like

a giant clock.

While

the Romantic revolt ran its radical course, governments, industries,

businesses, armies, schools, and nearly all of society’s other institutions

were quietly being organized along the lines suggested by the Enlightenment

world view. The more workable of the Romantic ideals (e.g., relief for the poor,

protection of children) were absorbed into the Enlightenment worldview as it kept

spreading until it reigned, first in the West, then gradually in more and more of

the world.

Crewe locomotive works,

England, 1848

At

this point, it is important to stress that whether or not political correctness

approves of the obvious conclusion we are heading toward, it is there to be

drawn and so should be stated explicitly. The Enlightenment worldview and the

social system that it spawned got results like no other ever had. It just worked.

European societies that operated under it kept increasing their populations,

their economic output, and, more tellingly, their control of the physical

resources of this planet. However, it is also important to stress that the

Westernizing process very often wasn’t even close to fair or just. Western

domination of this planet did happen, but in the twenty-first century, in most

of the West, we are ready to admit that while it has had good consequences, it

has had plenty of evil excesses as well.

Naval gun factory, Woolwich, England, c. 1897

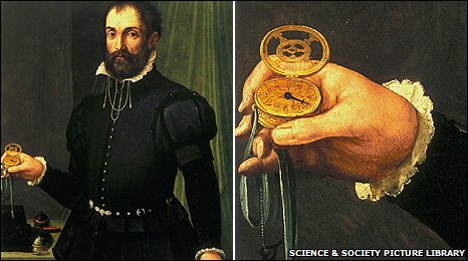

Renaissance pocket watch (from a painting by San Friano)

Renaissance pocket watch (from a painting by San Friano)  Battle of Rocroi, Thirty Years’ War (painting by Ferrer-Dalmau)

Battle of Rocroi, Thirty Years’ War (painting by Ferrer-Dalmau)

T

T