Chapter 6. (continued)

execution by hanging (Canada 1902)

This

Bayesian model of how we think is so radical that at first it eludes us. To

each individual, the idea that she is continually adjusting her entire mindset,

and that no parts of it, not even her deepest ideas of who she is or what

reality is, can ever be fully trusted is disturbing to say the least. Doubting

our most basic ideas is flirting on the edge of mental illness. Even

considering the possibility is upsetting. But this radical Bayesian view is certainly

the one I arrive at when I look back honestly over the changes I have undergone

in my own life. The Bayesian model of how a “self” is formed, and how it

evolves as the organism ages, fits the set of memories that I call “myself”

exactly.

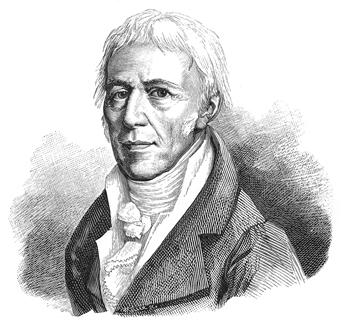

Thomas

Kuhn was the most famous of the philosophers who have examined the processes by

which people adopt a new theory, model, or way of knowing. His works focused

only on how scientists adopt a new scientific model, but his conclusions can be

applied to all human thinking. His most famous book proposes that all our ways

of knowing, even our most cherished ones, are tentative and arbitrary.2

Under his model of how human knowledge grows, humans advance from an obsolete

idea or model to a newer, more comprehensive one by paradigm shifts— that is by

leaps and starts rather than in a steady march of gradually growing

enlightenment. We “get”, and then start to think under, a new model for

organizing our thoughts by a kind of conversion experience, not by a gradual

process of persuasion and growing understanding.

Caution

and vigilance seem to be the only rational attitudes to take under such a view

of the universe and the human place in it. To many people, the idea that all of

the mind’s systems—and its systems for organizing systems and perhaps even its

overriding operating system, its sanity—are tentative and are subject to

constant revision seems even more than disturbing; it seems absurd. But then

again, cognitive dissonance theory would lead us to predict that humans would

quickly dismiss such a scary picture of themselves. We don’t like to see

ourselves as lacking in any unshakeable principles or beliefs. However,

evidence and experience suggest we are indeed almost completely lacking in

fixed concepts or beliefs, and we do nearly always evolve personally in those scary

ways. (Why I say nearly always and almost completely will become clear

shortly.)

Now,

at this point in the discussion, opponents of Bayesianism begin to marshal

their forces. Critics of Bayesianism give several varied reasons for continuing

to disagree with the Bayesian model, but I want to deal with just two of the

most telling—one is practical and evidence-based, and the other, which I’ll

discuss in the next chapter, is purely theoretical.

In

the first place, say the critics, Bayesianism simply can’t be an accurate model

of how humans think because humans violate Bayesian principles of rationality

every day. Every day, we commit acts that are at odds with what both reasoning

and experience have shown us is rational. Some societies still execute criminals.

Men continue to bully and exploit, even beat, women. Some adults still spank

children. We fear people who look different from us on no other grounds than

that they look different from us. We shun them even when we have evidence

showing there are many trustworthy individuals in that other group and many

untrustworthy ones in the group of people who look like us. We do these things

even when research indicates that such behaviour and beliefs are counterproductive.

Over

and over, we act in ways that are illogical by Bayesianism’s own standards. We

stake the best of our human and material resources on ways of behaving that

both reasoning and evidence say are not likely to work. Can Bayesianism account

for these glaring bits of evidence that are inconsistent with its model of

human thinking?