Chapter 14. (continued)

For

a page or so, let’s pursue this line of thought. We know that the matter in the

universe itself at levels of resolution far smaller than the simplest life

forms is pulled into its shapes—in fact, into its existence—by balanced sets of

opposing forces. The earth in its orbit is being pulled toward the sun by

gravity and flung away from the sun by centrifugal force. In this dynamic

state, our planet orbits through a band of space fit for the thing we call life. The nuclear strong force and weak

force alternately work to dissipate matter into nothingness or crush it out of

existence. In balance, they pull the nuclei of the atoms around us into their

shapes. Electrons are held in their orbits by balances of forces, like planets

and stars. As we find ways of balancing courage with wisdom and freedom with

love, humans mirror the universe itself.

We

need internal tensions in our communities. Pluralism is an indicator of a

dynamic, vigorous society. Societies that aim to be monolithic and homogenous

lack resourcefulness and vigor. A democracy may seem to its critics to be

enervated by the energy its people waste in endless arguing. But over time, in

a universe in which we can’t know what hazards may be coming in the next day,

year, or century, diversity and debate are what make us strong. Indulging in

self-deluding, wistful thoughts of ending uncertainty and its attached

anxieties leads us away from real love for our neighbors and from pluralism.

Therefore, love is not merely nice and pleasant: it’s vital. It has brought us

this far, and it is all that may save us.

A

basic Buddhist truth is that life is hard. Another is that only love can drive

out hate. Jesus’s number one command to us all: love one another as I have

loved you. These codes have not survived because a bunch of old men said they

should; they have survived because they enable their human carriers to survive.

In short, our oldest, most general values have survived because they work.

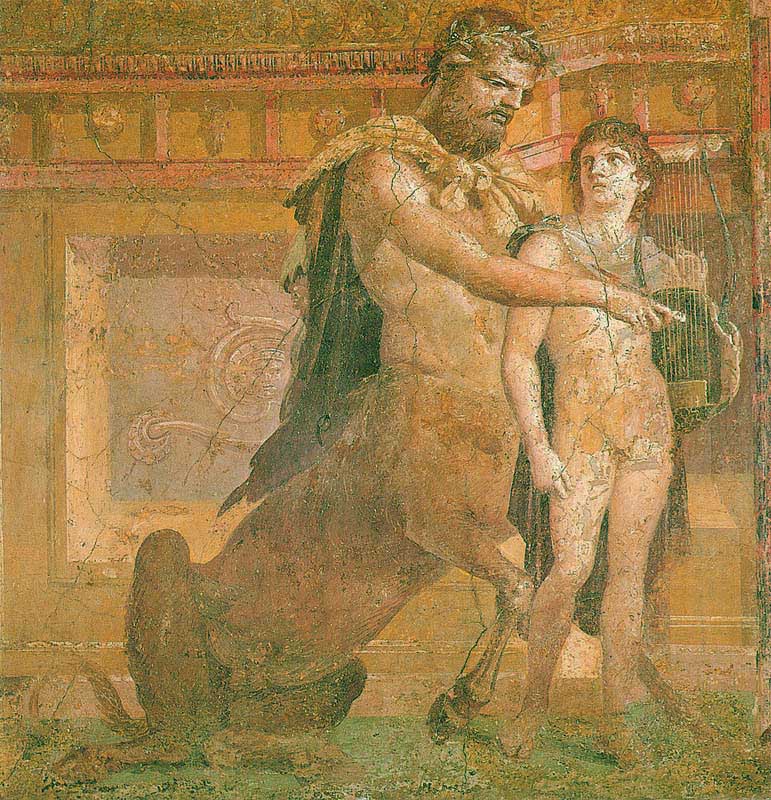

Socrates talking with

an Athenian woman (painting by Monsiau)

Courage

is the human answer to entropy, the adversity of reality. Wisdom tempers

courage. Freedom is the human response to (quantum) uncertainty. Love guides

freedom. Diligence, responsibility, humility, and many other values are hybrids

of the four prime ones. They show their real value only on a huge scale as the daily actions of millions of

people over thousands of years, in societies of increasingly greater internal

dynamism, keep evolving and getting good results. But values are not merely vacuous concepts or trivial preferences, like preferences for specific flavors of

ice cream or brands of perfume. They are large-scale human responses to what

is real.

The largest

purpose of philosophers is to give ordinary folk—by precept and example— such

clarity of understanding that people feel renewed and inspired to keep getting

up and trying again to get it right.

Notes

1.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, Thus Spake

Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, Part XXXIV, “Self-Surpassing” (1883;

Project Gutenberg). http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm#link2H_4_0004.

2. Kenelm

Henry Digby, The Broad Stone of Honour;

or, The True Sense and Practice of Chivalry, Vol. 2 (London: B. Quaritch,

1976). https://archive.org/details/broadstoneofhono02digbiala.

3.

Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present,

Chapter 11 (1843; The Literature Network). http://www.online-literature.com/thomas-carlyle/past-and-present/34/.

4. Melissa

Lane, “Ancient Political Philosophy,” Stanford

Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2014. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancient-political/#SocPla.

.jpg)