From

the nation to the person, some coherent code must be in place in order for us

to function, even if that code is mostly programmed into the subconscious.

People without any basic operating code in place can’t act at all. They are

called catatonic. The problem today

is that, for millions of people all over the world, the old moral codes that

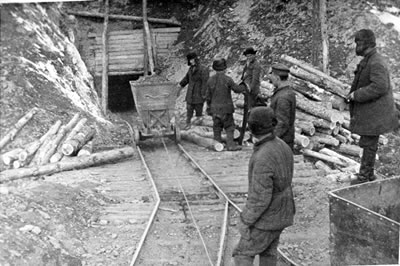

used to guide all human thought and action are fading. World War I was the

first in a series of real-world shocks that have deeply rocked all of our

beliefs—beliefs about the value of our science and, even more deeply, beliefs

about our codes of right and wrong.

So

let me reiterate: the worst fact about our moral dilemma in the twenty-first

century is that collectively, the gurus of Science, though able to achieve

amazing things in the realms of machines, chemicals, etc., have had nothing to

say about how we should or should not be using these technologies. Many of them

even go so far as to claim that should

is a word that has no meaning in Science.

It

seems bitterly unfair that the same science that eroded our moral beliefs

offered nothing to put in their place. But what seems more cruelly ironic is

that at the same time as Science was destroying our religious and moral

beliefs, it was putting into our hands technologies of such destructive power

that the question that arises is whether any individual or group of individuals

could ever be moral enough to handle them responsibly.

We

are living in a time of terrifying uncertainty. We now have the weapons to

scorch our planet in one afternoon—so completely that the chances of our

species surviving in that post-apocalyptic world are effectively zero.

Furthermore,

even if we escape the holocaust of nuclear war, we are steadily polluting our

planet. We’re aware of this, but we can’t seem to stop, even though the vast

majority of the scientists who study the earth and its ecosystems say that the

point of no return is rapidly approaching. To people who have studied the earth

and its systems, the risk of environmental collapse is even more frightening

than that of nuclear war.

Large

numbers of us, in the meantime, “lack all conviction.” Without a moral code to

guide us—one we truly believe is founded in the real world—we are like deer on

the highway, paralyzed in the headlights, seemingly incapable of recognizing

our peril.

Most

reasonable, informed people today know these things. In fact, we are so weary

of hearing what are called the “dire predictions” that we don’t want to think

about them anymore. Or we think, get scared, then go out with our friends to

get inebriated. There seems to be little else one ordinary person or even

clusters of powerful persons can do. The problems are too big and too insidious

for us—individually or collectively. Shut it out. Forget about it. Try to live

decently. Hope for the best.

For

me, none of these answers are good enough. To ignore all of the evidence and

arguments and resign myself to the “inevitable” is to give in to a whole way of

thinking I cannot accept. That way of thinking suggests that the events of

human lives are determined by forces that are beyond human control.

I

disagree. I have to. I believe true philosophers must.

Whether

we are discussing the cynicism of people who focus on events in their personal

lives or the cynicism of people who study human history, or cynicism at any

level in between, I have to tell these cynics bluntly, “If you really thought

that way, we wouldn’t be having this debate because you wouldn’t be here.”

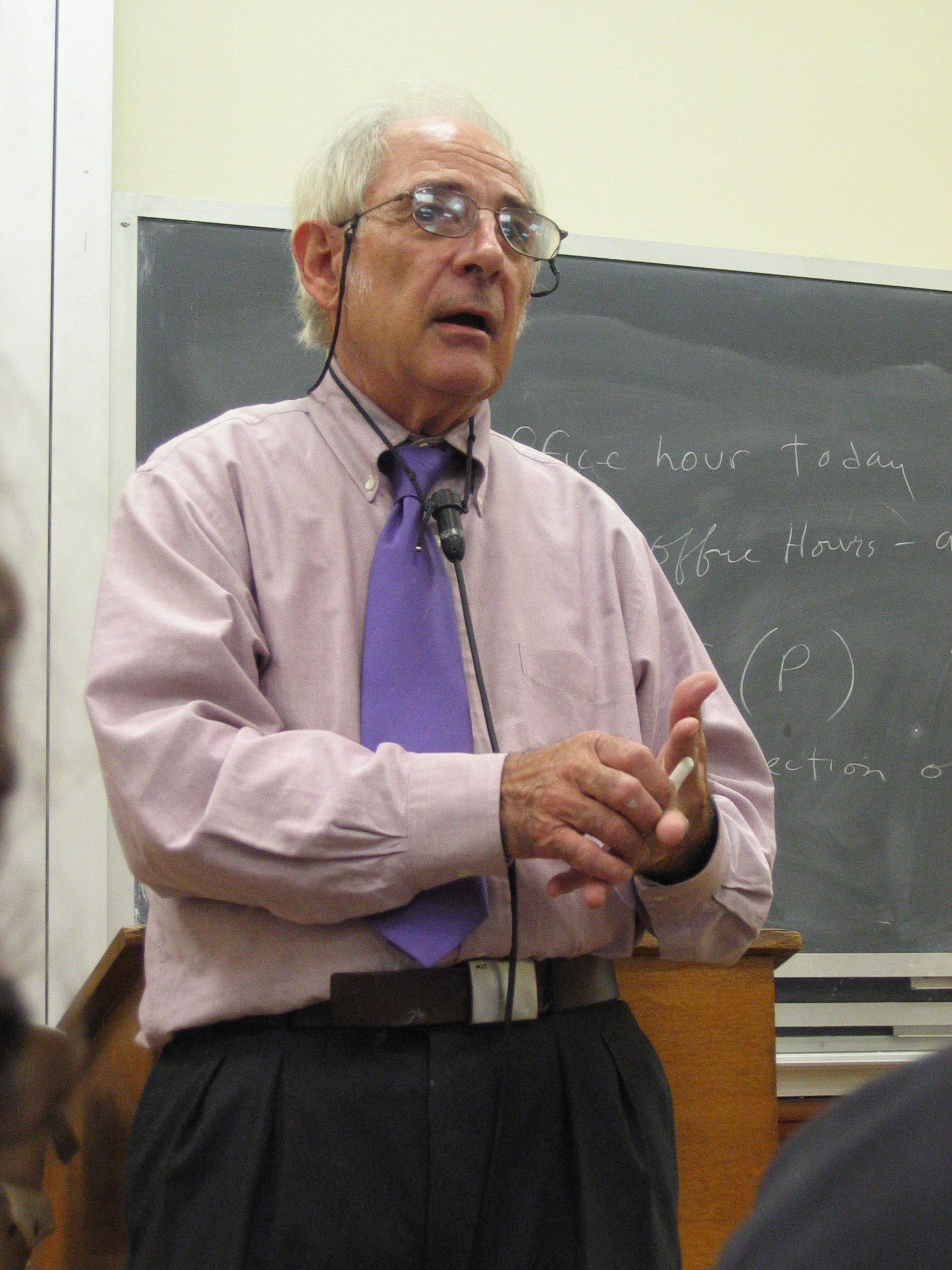

Albert Camus, French philosopher (1913–1960) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

As

Albert Camus sees it, suicide is the sincerest of all acts.6 Its

only equal in sincerity is the living of a genuine life. A genuine person stays

on in this world by conscious choice, not by inertia. A genuine person is still

here because he or she chooses to be. Insincere people may claim to be totally

disillusioned with this world and other people in it, but that simply can’t be

the case if they are still alive and talking. These people are only

partitioning up their minds, for the time being, into the manageable

compartments of cynicism. But the disillusionment they feel now—on any scale,

personal to global—is going to seem minor compared with that which they will one

day feel with themselves, one day when their fragile mental partitions begin to

give way. And it doesn’t have to be that way, as we shall see.

So,

to sum up our case so far, what have we shown? First, that Science has undercut

and eroded the old beliefs in God and the old codes of right and wrong. Second,

that because of our ongoing need just to manage our lives and, even more

importantly, because of our recently acquired and constantly growing need to

manage wisely the physical powers that Science has put into our hands, we must replace

the moral code we no longer believe in with one we do believe in. Perhaps then we

will have a chance to live, go on, and get past our present peril.

If

we can work out a moral code we truly believe in, and if it really is congruent

with physical reality, will it lead us on to a renewed belief in a Supreme Being? That

question is one I will set aside for now, but I will deal with it in the last

chapter of this book. For now, let’s set our sights on trying to begin to build

a new moral code for this era, so that finally we may confront and quell “the

worst” among us. And the worst in us.

Notes

1. Ruth Benedict, “Anthropology and

the Abnormal,” Journal of General

Psychology, 10 (1934). http://www.colorado.edu/philosophy/heathwood/pdf/benedict_relativism.pdf.

2. Thomas Kuhn, The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 3rd ed., 1996).

3. John Searle, Minds,

Brains and Science (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

4. Harold Kincaid, Philosophical

Foundations of the Social Sciences: Analyzing Controversies in Social Research

(New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

5. Marvin Harris, Theories

of Culture in Postmodern Times (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 1999).

6. Albert

Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, trans. Justin O’Brien (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin

Books, 1975), p. 11.