Huckleberry, the Classic

Just

before Christmas. A hopeful, positive view of humanity.

I

am a retired English 11 and 12 teacher up in B.C. who, back a few years ago,

taught a number of American novels and enjoyed several of them thoroughly. “To

Kill A Mockingbird” was a special favorite, but I did also teach one that is

now very controversial in the US itself, namely “Huckleberry Finn”.

This

novel is now controversial in a number of school districts in the US, as I

understand it, because in it, the “n” word for African Americans is used many

times. This is very politically incorrect for many people, and I sympathize

with their feelings, but I think any district or state that bans this novel is

making a big mistake.

I first read HF when I was about 14, but I knew even then how beautiful its outlook on people and the world was.

Why would I say such a thing?

There

is a very simple answer to this question: the novel contains an explicit scene

which shows something basic about humans, at least in Mark Twain’s view, which

may be the most optimistic view of humanity in all of literature.

As

Huck and his negro companion, Jim, are journeying down the Mississippi on a

simple, home-made raft, they are met by a couple of slavecatchers on another

raft. Huck knows well what they want. They want to know whether he has seen any

negroes on any raft or shore during his journey. If they can find and catch

such a person who is a runaway slave, they stand a good chance of getting a

generous reward from the slave’s owner and perhaps from the state government as

well. Jim is hiding in the shack that they have on the raft and the

slavecatchers are foiled by a ploy of Huck’s. But he knows that if he lets Jim

escape pursuit completely, maybe even helps Jim to avoid capture, then Huck himself will

become an accomplice to a very serious felony.

Huck

and most of the people in the South in those times had been raised to think

that a slave is not fully human; he is property. By escaping from his slave

life, Jim is stealing himself from Miss Watson back in Huck’s hometown. As Huck

says, Miss Watson never did anything bad to him, and Jim is a very valuable

piece of property. Huck, by helping Jim to escape, is committing grand larceny.

Huck has been raised to believe that he is about to commit a mortal sin. He is

very scared for a while as he considers his options while Jim sleeps in the

shack.

But

as he considers his choices, Huck is also thinking about all the times that Jim

has taken care of him, and how Jim calls him “Huck honey” with real affection.

Huck’s own father was a drunken, child-beating monster. If ever a kid had

reasons to be bitter, that kid is Huck. But on the positive side, in a very

deep way, Jim is the closest thing to a loving dad that Huck has ever had.

Huck

decides that even if it means he will burn in Hell for all eternity, he can’t

and won’t turn Jim in to the slave catchers or any of the authorities in the

towns they are passing along the river either.

Why

do I value this scene so much and make such grand claims for it?

Because

I believe Twain is showing us something so fundamental about human beings here

that the scene can still sometimes move me to tears.

Nowadays,

I think 95% of the people of the world would say that Huck did the right thing.

Huck’s humanity overcame the conditioning that his culture had put into his

head for all his life so far. Jim is a good man. A good human being. He is a slave

purely by chance, the luck of a draw that he did not set up and cannot change.

The value of one human being – to Huck, Twain, and me – outweighs all the

prejudices that Huck has been taught by his sick culture.

And

make no mistake about it: Huck has been through about as much as any kid could

take and still come out sane. His dad beats him. His dad is such a bad drinker

that he regularly has delirium tremens. His dad is a thief and a liar with no

redeeming features whatsoever. The only reason he had even come back into

Huck’s life was because Huck had come into some money. Old Finn is angling to

get his hands on that dough from the time he comes back into Huck’s life, which

is early in the novel.

But

the decency in Huck’s own character will not be denied.

The

conclusion to be drawn from this scene is very simple: the basic nature of

human beings, for most of them, is very, very good. So much so that even a life

of abuse and brainwashing can’t turn Huck into the kind of monster that his

father is.

There

is more interesting plotting and character development in “Huckleberry Finn”,

but for me, that one scene in the middle is worth the price of the book.

And

let me be even clearer here. I taught kids from 12 to 19 for 33 long years. Did

I ever meet up with a kid like Huck, a kid who turned out well in spite of a

nightmare childhood? You bet I did. Kids who were going home every day to one

or two drunken parents and three younger siblings and who were taking care of

the whole household when they were under 18 years old. For me, based on real

life experience, Twain is right. Most human beings are very good.

So

my American friends, don’t let this book go. If some of the terms in the book

are offensive to some people, that doesn’t matter near as much as the worldview

that it offers to teenagers (in high school) and to us all. And in defense of HF,

Huck and his friends only speak with the terms people in that time used. HF is

largely an accurate reflection of the times that it describes, times we would

do well to keep in mind – so they don’t happen again.

The

offended ones will get over their discomfort if they just have a good English teacher

to study this book with them.

There is hope for any species that contains even small numbers of Huckleberry Finns. Absolutely. We aren’t just bags of meanness and farts. We really do have some humane qualities of incredible beauty and decency.

(Enjoy

your day, lads and lassies. And thank you for visiting my blog.)

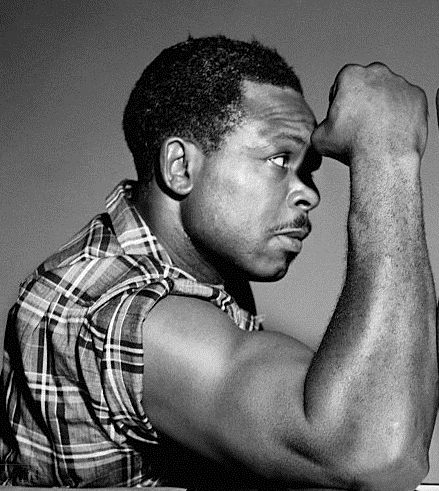

Archie Moore in his prime (credit: Wikimedia Commons)