Castle Bravo thermo-nuclear test (Bikini Atoll, 1954)

(credit: United States Department of Energy, via Wikimedia Commons)

A

major plank in the structure that supports moral realism comes to us from the

study of History. Just how desperate the peril of our current situation is may not

be clear to casual observers, but if we are human and we are like our forebears

in our basic natures, then yes, desperate

peril is not too strong a term. There is a pattern in History, and we must

see it and work to stay out of it quite simply because this time, we truly must

not repeat it.

Sky burial, Tibet

(credit: FishOil, via Wikimedia Commons)

History

can be fascinating to study and we can easily get lost in its territories. There

are many variations in how humans form communities and nations, so many that we

can easily, as the saying goes in English, fail to see the forest for the trees.

For example, how different societies handle death can vary in fascinating ways.

Some cultures insist that burial of their dead in the earth, with certain

prescribed rites accompanying the burial, is the only way to deal with death

respectfully (the West). Others insist that burning of the corpse is the right

way to deal with death (India). Others feed the corpses of their dead to birds

of prey (Tibet). Still others ceremoniously eat the corpses of their dead and

are revolted by the very thought of burying them (ancient Callatiae).

We

can also get lost in the legal records of trials during the reign of Louis XIV

or the 1936 membership lists of the Nazi party in Frankfort or the names of the

commissars in 1941 Sevastopol or the ministers in the cabinet of some Chinese emperor

of the Song dynasty. And on and on.

But

these kinds of side-trips are tiring, frivolous distractions. They are not what

the study of History should be about.

So

what should the study of History be about?

We

must try to understand why humans in large

groups – tribes and nations – do the things they do, not just look at what they

do. Our intention in these times must be to comprehend how human societies evolve,

with our ultimate aim being to detour around the worst kinds of group behavior

and so to keep our species from annihilating itself.

An

encouraging thing to note is that if we study enough History from all over the

world and in all eras, we really can draw some fairly confident conclusions.

The first is this: while the cosmetic details of societies may differ a great

deal, all societies have a core program of concepts, values, beliefs, customs,

etc. that enables them to survive. The point is that a society’s beliefs and

morés are not just arbitrary. The large majority of citizens in every society is

programmed with concepts, customs, etc. that steer them into patterns of

behavior which enable them to live together, get food, build shelters, find

mates, have children, nurture/raise them, fight off invaders, and thus to survive

as a culture/nation.

Every society – via its parenting styles, schools, churches,

media, etc. – aims and acts to extend itself forward in time.

bust of ancient historian, Herodotus

(credit: Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, via Wikimedia Commons)

Next,

about human societies, we can also say that in all of them, the citizens

generally get so used to their society’s beliefs, morés, customs, etc. that

they see their way of life as being just human and “normal”. Herodotus found

over 2400 years ago, that all human beings tend to see the customs they grew up

with in this way. (“Custom is king.”)

It

is worth noting here that in the real world of hard facts, there is no single “right”

way of life, even in a given location and a specific era. Many ways of life can

work in any location to give their citizens full, healthy lives along with a

capacity to breed and pass their ways of behaving on to their children. Even in

one specific locale, where the ecosystem contains resources that are obvious

and easy to exploit, many different ways of life with many different

technologies for using the resources can arise. Central Europe has contained

many varied tribes, each with its own customs for literally millennia, often

living side by side (and too often in the past hating each other).

There

is no single “right” way for humans anywhere ever, but in theory, it is

possible that under a larger, global system of ideas and customs, all of the world’s cultures/nations could coexist and get along.

This

brings us to an even more important insight into History: human tribes in all

parts of the world for millennia have shown discomfort when they met a different

tribe. Then hostility, then violence. And it isn’t that two tribes can never

work out agreements under which they may live side-by-side in peace, even

trading to their mutual benefit. But it has been easier for neighboring tribes,

even formerly friendly ones, to slip into hostility and war. Humans in their

groups have made war on each other as naturally as the sun rises and sets, all

over the world for a very long time. Right back to the Australopithecines.

My

first intention today, then, is to say again that we can’t do war anymore, no

matter how “natural” that way has been for us in the past. We have nuclear

weapons now. The way of the past – if we slip into it – will finish us. But

also I want to say today that I think there is a way out. It is a long, slow,

arduous, tedious one, but I don’t see any other, and once we know there is but one path to our survival, we must set out on it. Determinedly.

We

are going to have to overtly, explicitly teach the kids – all the kids – to

live together and get along. Teach them over decades, even generations if

necessary. No one tribe's stories or mores or traditions matter anything like as much as this larger objective.

What

we must not do is rely on our old belief systems that tell us to acquiesce in

our current ways of life. That has been the course adopted by billions of

decent people all over the world in the past. Adopted because acquiescence and vaguely

defined hopes were the paths commended to them by their leaders.

We

must do better. We must fix our sights on doable social change and begin to

employ the practical means that we have to create that change.

It

is worth going off on a tangent for a moment here. We must not be surprised

that the leaders of the past – religious, secular, military, political, etc. –

in all parts of the world – told their followers to trust in them and in their

tribe’s beliefs and customs. Cognitive dissonance theory predicts that is what

leaders will do because that is how they justify, and keep, their jobs. But in

the nuclear age, we are going to have to become a population worthy of democracy

– all the adult citizens of the nation involved in the nation’s affairs as a

given of daily life. We are going to need all of that wisdom to stay out of the

patterns that have been the normal human way for centuries. Democracy is the

one way by which we may be able to stop the unthinkable from occurring. We must

not trust our leaders in the blind way that our forebears did. We must all get into

the game.

The

subtlest lesson we can glean from studying History is that people hanging on to

what is familiar, hoping for the best, and letting events take their course is

a recipe for disaster. We must grow neither cynical nor resigned. People have

before. We can see what it got them. We can do better in this time. We have the

means in our hands. No more vague hoping, no more cynical ennui.

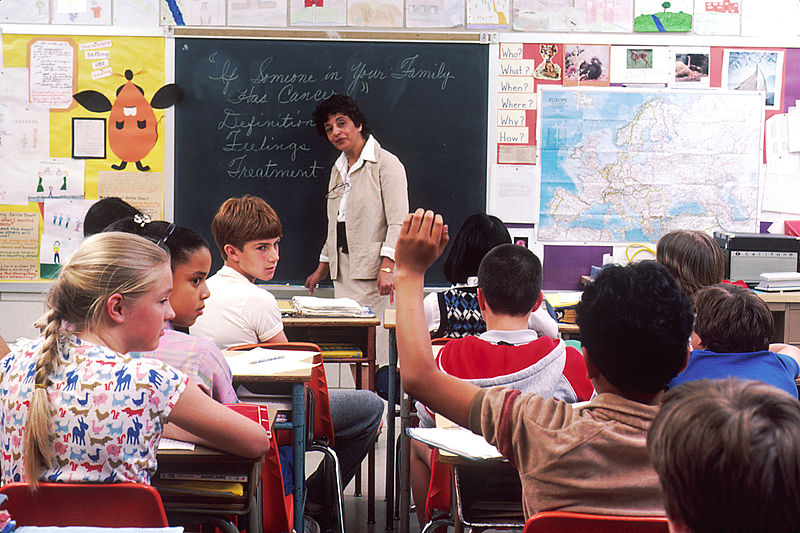

pupil and teacher (Mauritius, 2007)

(credit: Avinash Meetoo, via Wikimedia Commons)

We

can do better now because we know that the education of the kids is the future.

As we shape the twigs, for the most part, so the branches will grow. As we

educate the kids, so the future will be programmed. If we teach them distrust

and suspicion of other cultures, those traits will characterize their adult lives.

If we teach them responsibility and compassion, those traits will come to the

fore.

pupils and teacher (U.S., 2013)

(credit: Michael Anderson, via Wikimedia Commons)

We

can’t educate kids out of some things, of course. They will have to work and eat.

They will need to have and raise their own kids. And so on. Some traits of

humans are unalterable.

But

we can train them in the skills of citizenship in a democracy. To spot and

neutralize the bullies of the world as those bullies vie for power. To mediate

disputes among them by peaceful means. To compete in peaceful ways – sports,

the market, academia. And to reach out to folk in other nations. To talk, work,

and live together, and get along.

The records of the many

and varied nations of the past show that we will not escape the war-fate of our

forefathers if we don’t work specifically, with focus and drive, toward peace

in our societies all over the world. The one obvious, practical means by

which we can do that is in the schools. Teach the kids to build peace.

No

more docility. The trusting folk of the twentieth century got ground up. WWI.

WWII. Next time, if we let it come, will be much worse.

So

let me close by getting even more specific.

My

suggestion? We need a Social Studies course and a World Literature course all students

in the world can take. U.N. developed and recommended. The Discipline and Practice

of World Peace. World Lit. for the World.

Radical?

Yes. But my final, emphatic point today is this: I believe we have no other

choice but to re-design the kids’ studies and then teach those new courses to them.

There is no other practical way to shape

the future of our species, and there is no one else to do this work but us.

We

must work via the means we have toward the prime objective: a population in the

next generation who live together, all over the world, in basic, daily

confluence. The subtle lesson of History is that trusting in our old,

familiar ways is the essence of tribalism, and tribalistic complacence, over

and over, everywhere, is what has made human history so bloody for tribe after

tribe in place after place. We must learn to change by choice instead of by

pain.

Perhaps,

war kept us strong in the past. Hitler thought so. But our Science has made war obsolete. All that is needed for peace to come is for us to truly see that.

The

lesson of History so far is that all through history, people haven’t learned

from History. They have grown weary of politics and consigned their fates over

to elites. The vague, effete cynicism of the postmoderns today is just a version

of this same indolent naivete, but with a bigger vocabulary.

Democracy

asks of us the best we have, yes. But it does not fail us. We fail it.

Teach

the kids – articulately and with openly avowed intention – what world peace will

look like and, step by step, how it will be achieved. Training in conflict

resolution. Competition. It’s human for us to need it. But competition carefully

balanced with respect for the rules and the spirit of the game. Grace in

victory and in defeat. Love of a game played well by sportsmanlike players. Love

of learning, in classrooms where some are always going to shine more than

others, but where it is considered rude to flaunt that cleverness. Knowledge

of the signs of tyranny jockeying for power. Knowledge of the democratic

machinery in our systems of governance that enables us to stop those tyrants

while they are small.

The

measures that can be taken – the things we could teach – are known to us. Now

we must teach them.

Michelle Obama with Quantico high school graduates (2011)

(credit: Linda Hosek, via Wikimedia Commons)

Our

weapons have grown up. Now, so must we.

In

the shadow of the mushroom cloud, nevertheless, have a determined, willful,

youth-oriented day.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.