Chapter 17 The Morally Crucial Features Of Modern

Physics

At last, we’re ready

to tackle the moral challenge head on, to derive ought from is. The

question now is: How should a moral code that is based on the most general

principles of the empirical world work? Where do our best odds lie?

Note again that it’s

the big constants of the universe that we want to resonate with. Our moral

code, if it is well-designed, should match our best worldview, the one we get

from Science. And even when we know what those big constants are, we still have

many ways in which to design a society with strong survival odds. The larger

point is that whatever design we choose, or in the past, social evolution

chose, there are still massive principles which we must accommodate. This

picture is very different than the one we get from moral relativism. It offers no

guidelines at all for us to follow as we design a new code for society.

An analogy with the

biological world fits well here. Life forms are so varied that a life sciences

student can get lost in studying any one of millions of species for the rest of

her/his life. But there are giant constants that are essential for all living

things. For example, respiration, by which all living things get energy. Or

body temperature regulation, since all life forms on our planet can only exist

in a narrow band of temperatures. Then pH, etc.. To understand life, we first seek

the big constants, the ones that govern life for paramecia, parrots, people, and

piranhas. These concepts are basic if we are to understand Biology. Similarly, we

must also grasp the largest principles of physical reality if we wish to see

how Physics should inform our moral values.

For our moral code, the

two most important features of the modern scientific worldview are entropy and

uncertainty.

Understanding entropy

means that we must accept that the universe is heading toward a final state in

which all the sub-atomic particles will be spread across it at a

temperature of absolute zero. We don’t understand numbers that big, but that

doesn’t matter. Physics tells us that the heat death of the universe is

inevitable. (On the other hand, it isn’t due for over five billion

years.)

To humans, who are

energy-concentrated living things, this means that we exist against the natural

flow of the physical universe. The level of disorganization or “burnt-outness” of

the universe is always increasing. This is the first major thing that Physics

has to say to Moral Philosophy.

(credit: Profberger, via Wikimedia Commons)

The second feature of

reality that matters to our new moral code is uncertainty. In order to adapt to

uncertainty, obviously, humans must learn to make provision, ever more

effectively, for the varying probabilities of future events.

Probabilities range

from the likelihood that it will rain this afternoon, to the likelihood that

there's a leopard in the grass nearby, to the likelihood that Germany will

attack Russia given what Hitler said about Germany’s need for living

space. We design our actions and live our lives by odds-making.

Our deep belief that

life is always full of toil is our way of understanding entropy. Our deep

belief that life also contains constant hazards, in addition to the constant hard

work, is our way of understanding uncertainty.

Over thousands of

years and billions of people, values enable the survival of a human society

only if those values reflect the forces underlying physical reality, or to be

more precise, successful values must cause humans to behave in ways that

accommodate adversity and uncertainty, especially for whole societies over the

long term. Successful values, riding in their human carriers, thus go on.

Our values in modern

democracies have been fairly effective at guiding us to survive and spread,

though not always in humane ways. Over millennia, the demands of survival in a

hazardous reality have caused us to work out a set of values, morés, and

behaviors that (mostly) guide us to handle both adversity and uncertainty. If

we and our forebears had not learned and implemented these basic values lessons

at least moderately well, we wouldn’t be here. Having children is hereditary:

if your parents didn’t have any, you won’t have any.

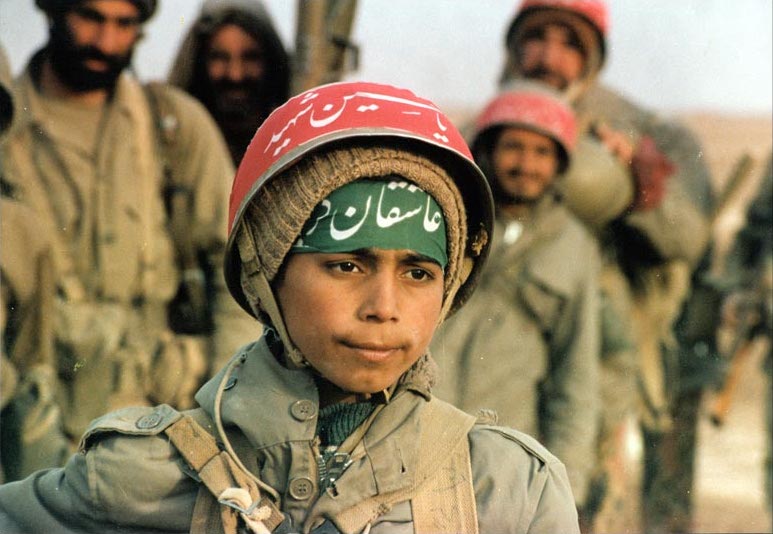

Young

patriot (credit: US Army, via Wikimedia Commons)

Chinese children (PRC) in Young

Pioneers (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Russian children in

Vladimir Lenin Pioneers (1983)

(credit: Yuryi

Abramochkin, via Wikimedia Commons)

Iranian boy soldier during Iran-Iraq War

(1980 – 88)

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

But we don’t yet

comprehend the biggest of these truths in a conscious way.

Most people of every

nationality still see their values as being exempt from analysis because we all

get programmed as children to be deeply, unswervingly loyal to our tribe’s

values. This kind of programming has made the majority of people in most

societies, both historical and modern, into unthinking pawns of their society’s

cultural code. A major purpose of this book is to help thoughtful readers

become aware of values and draw them into consciousness as concepts that they

can analyze and discuss.

Thus, we are now

ready to ask: What are the values that enable humans to respond to the endless,

uphill struggle of life, the main consequence of entropy, the characteristic of

life we call adversity?

A whole array of

values should be taught to young people to enable them and their culture to

deal with adversity over generations and centuries. In order to deal well with

adversity, a society needs large numbers of people willing to face exertion, exhaustion,

struggle, and pain. In fact, a society proves most effective if its citizens

take up the offensive against the relentless decay of the universe. Children

taught to seek challenge become adults who bring new territories (one day,

planets) under their tribe’s control, devise new ways of growing food and making

shelters, use technology to do more work with less human exertion, and, in

general, perform the tasks of survival more and more efficiently.

When we generalize

about what these entropy-driven behavior clusters have in common, we derive two

large, generic values that are found in all cultures; these are courage and wisdom.

In different cultures

all over the world, courage is instilled in the young, which is what we would

expect if it really does work. Bergson spoke of élan, Nietzsche of

the will to power.1 Face adversity, kids. Tackle it

head on.

Japanese samurai

lived by bushido, their code of total discipline, and European

nations lived by a similar code, chivalry, right into modern times.

Beyond the difficulties of translation from culture to culture and era to era,

we see in all these values a common motif: they all direct their disciples to

persevere through challenges of all kinds, even to seek challenge out. In

ancient Greek myth, Achilles chose a brief, hard life of honor over a longer,

easier one of obscurity. For centuries, the ancient Greeks considered him to be

a model of a man, as do some people in nations that have absorbed many of the

values of ancient Greek culture to this day. And many non-Western cultures have

similar heroes.

The Triumph of Achilles (credit: Franz

Matsch, via Wikimedia Commons)

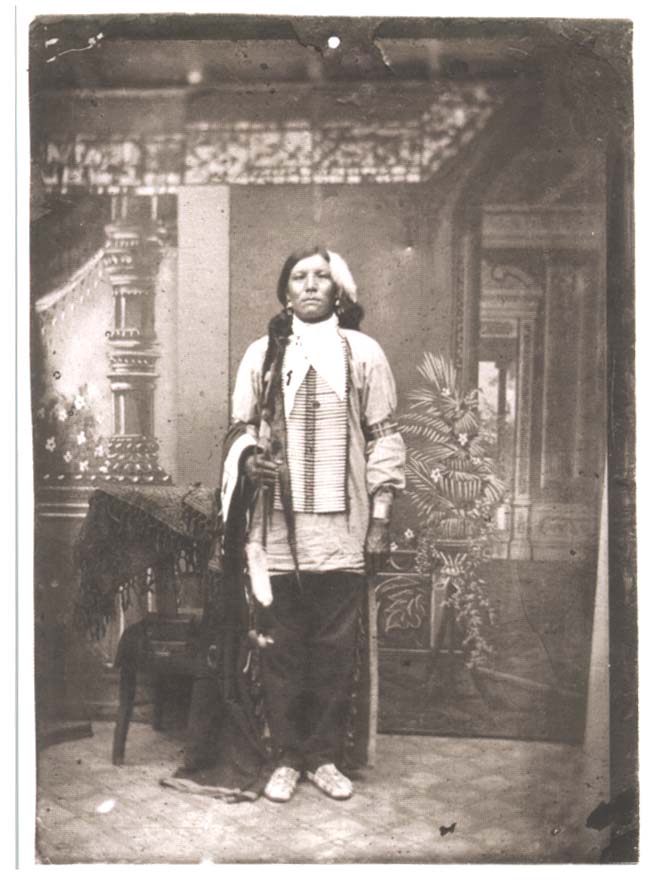

Photo believed

to be of Apache leader Crazy Horse, c. 1877

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Statue of Zulu leader, Shaka

(credit: Jacob

Truedson Demitz, via Wikimedia Commons)

Martial arts master and Chinese hero,

Huo Yuanjia

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

Confucius said that

the superior man thinks always of virtue, while the inferior man thinks always

of comfort. Nineteenth-century English writer K.H. Digby said: “Chivalry is

only a name for that general spirit or state of mind which disposes men to heroic

actions and keeps them conversant with all that is beautiful and sublime in the

intellectual and moral world.”2

The exhortation to

meet and even seek adversity, and to reject easy paths and lifestyles, echoes

through all societies. Young people everywhere are especially encouraged to

face hazards for the defense and promotion of their nations. We can sum up the

gist of all of these values by saying that they are built around the principle

that in English is called courage.

It is familiar and

clichéd to push young people to aspire to courage. But clichés get to be

clichés because they express something true. In the hard background of the

physical universe, life seeks to create stable, growing pockets of order. In

the case of humans, it does so by programming into young people an entire

constellation of values around the prime value called “courage”. Behaviors that

meet and overcome adversity enable those who practice them to move forward. As

a result, societies that believe in courage survive better because of that

belief.

And now we come to a

subtler insight. The value society instills into its young to make them seek

out and conquer adversity must be balanced with a second value that will cause

the energy put into facing challenges to be focused so the individual will deal

with the challenges efficiently. There is nothing to be gained by teaching

young people blind aggression; it will only run amok in its own society and

sometimes other societies. Eager-but-directionless young people end up hurting

themselves in car crashes, daredevil stunts, and street fights, while

accomplishing little or nothing in useful, material terms for their nations.

The courage-tempering

value is usually called wisdom, but knowledge and judgement

are also terms in English for this same value. Wisdom has the effect of focusing

humans actions to achieve objectives by behavior patterns that employ energy

efficiently. It is seen clearly in the medieval code of chivalry and the

samurai warriors’ code of bushido, both of which contain instruction

on how a man may be simultaneously both brave and smart. Warrior and

poet.

Note that the idea of

balance is implied all through my model. Societies, like living species, become

extremely complex, internally and in their dealings with each other. But balance

is an ideal in all cultures (even more so in the Far East than it is in the

cultures of the West).

In ancient Greece,

Aristotle told his followers to seek moderation. For example, in his view, balance

between foolhardiness and cowardice is what makes courage. And stinginess must

be balanced against extravagancy if we are to reach a prudent way of handling

money, and so on for a whole list of virtues.

The religions of the

East, like Taoism and Buddhism, go so far as to say that the whole picture our

minds have of reality as if it were made of separate, opposite traits is illusory.

For Buddha and Lao Tse, reality is an unbroken whole with no seams. Our minds

think they see separate entities like good and evil, life and death, past and

future, rich and poor, but in reality, there are no such things. We get free of

our suffering, they say, when we let all our categories go and become one with

everything. Then, even the most tedious forms of work can be done with dignity

if they are done with mindfulness of their place in the whole picture of

things. Weeding a garden or digging a pit mindfully can be dignified.

Not surprisingly,

there are echoes of this balancing of courage and wisdom embedded in mythology.

Myths were the life-guides for early tribes. The Greek mythic heroes Jason,

Achilles, Perseus, Theseus, and Aeneas all needed Chiron, the wise teacher.

Among the early Britons, Arthur needed Merlin. In modern myths, Luke Skywalker

needs Yoda, Dorothy, Glinda, and Katniss, Haymitch. These pairs all portray courage

tempered with wisdom.

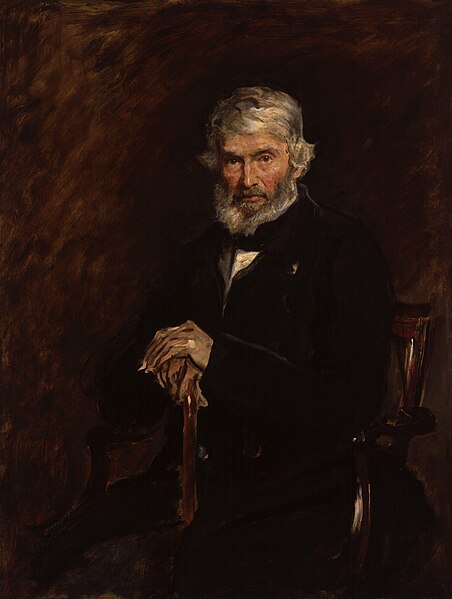

Thomas Carlyle (artist, J.E.

Millais)

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The most familiar

moral value that is a hybrid of courage and wisdom is what we call work. Diligence and

conscientiousness are two of its other names, as most of us are

wearily aware. But the dreary, tedious, clichéd feel of this values cluster

should not discourage us. Clichés, like this one about the nobleness of work,

become clichés because they express something that is universally true.

“I'm a greater believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I

have of it.” (Thomas Jefferson)

“Genius is 1%

inspiration and 99% perspiration.” (Edison)

Courage is good.

Wisdom is good. We learn as children that if we want to achieve great things,

we must learn both courage and wisdom. In practice, the combination of the two

always results in hard work.

Thomas Carlyle distilled the idea well:

“For there is a

perennial nobleness, and even sacredness, in Work. Were he never so benighted,

forgetful of his high calling, there is always hope in a man that actually and

earnestly works: in Idleness alone is there perpetual despair. Work, never so

Mammonish, mean, is in communication with Nature; the real desire to get Work

done will itself lead one more and more to truth, to Nature’s appointments and

regulations, which are truth.” 3

(credit: Chuck

Kennedy, via Wikimedia Commons)

This is the moral

realist view of how the fact of entropy informs the values and behaviors of

human societies. A lot of varied societies can still emerge in real life, but

all that last must teach hard work as a way of life. The giant picture we’re

drawing here leaves plenty of room for variety in human cultures, but they are

not chaotic and random, as moral relativism would have us believe.

But what about the

second big trait of reality, namely quantum uncertainty?

As with courage and

wisdom, a balanced pair of values shapes the behavior of citizens as societies strive

to deal with reality. For a society to maximize its chances of handling the

uncertainty of existence – the unexpected events that keep coming at us – that

society must contain as wide a variety of responses to the challenges of the physical

world as the people in the society can learn to master. In a scary world, if

you’re smart, you try to learn skills that will make you resourceful and

versatile so that you can be ready for (almost) anything.

Encouraging each

individual to aim to be versatile (the Renaissance man concept) helps, but the

really important value a wise society instills into all its members is a love

of freedom: a desire in every child to become her/his best self and to show a

generosity of spirit that encourages others to do the same.

To be equipped to

meet the widest range of futures possible, a society must contain the widest

range of humans possible, with skills and talents of every sort imaginable. If

an unforeseeable crisis threatens a freedom-loving society, that society has a

higher likelihood of containing a small group of people, or even just one

individual, who will be able to react effectively to the situation than a more

homogenous society ever can. Then the effective ones can teach the rest how to

survive the current crisis. The free society just has a lot of kinds of folks

to draw its resources from.

In addition, in more

ordinary times, when a society is maintaining a steady state, the people in a diverse

society pursue a wide range of activities, research a wide range of topics, and

develop a wide range of services and products. Any of these may yield benefits

for the whole society. Against the uncertainty of the universe, free societies

don’t just hedge their bets. They become proactive.

Which

activities will turn out to be more than just hobbies in a decade or two can’t

be known in an uncertain universe. Some of these hobby activities will fit into

the society’ social ecosystem and, in a decade or so, become simply parts of the

division of labour. Others will prove to be silly wastes of time. Still others

will lead to brilliant innovations that will make that society leap forward.

Therefore, a wise

society cultivates diversity and also cultivates its dreamers. Occasionally, an

eccentric invents something that is amazingly useful to all. The presence of

eccentrics in a society is proof that freedom is part of that

society’s moral code. In any society, in the long run, the more uniform its

people are, the lower are that society’s odds of survival. On the other hand,

pluralistic societies, over the long haul, adapt better to new challenges, and

thus, they survive.

To focus this value

called freedom, in the way wisdom balances courage, society must

teach love. Left unbalanced, freedom leads to fissioning. Factions form,

and they gradually become mutually suspicious and hostile. But to balance the

hazards of freedom, we can teach love. Brotherhood. Agape. As courage

plus wisdom yields work, so freedom plus love yields democracy.

A society with a wide

range of behaviors and lifestyles practiced among its citizens must also teach

these same citizens to respect one another’s property and rights. If it

doesn’t, that society will be constantly torn by violence between its various

factions. No matter which wins, some of that society’s versatility will be lost,

a net loss for all. Thus, in all long-enduring societies, some

form of love for one’s fellow citizens has always been taught to each new

generation.

New technology: cannon ca. 1430 (credit: Jan Rehschuh, Wikimedia Commons)

The most basic form

that this love takes is mutual respect, and it is realized in a code of laws.

In a democracy, the laws are drawn up by representatives of the people. (In an

autocracy, the laws are whatever the autocrat says they are, but since he/she

is just one person, the laws tend to be inconsistent and inadequate. This is

why most autocracies need to use repression to keep their people in line.)

Thus, in a democracy,

the citizens must cooperate to build and maintain a legal system that will

enable them to work, do business, raise families, settle disputes, and through

all these activities, just live in community and get along.

But laws can only

work if the people trying to live under them respect not so much the exact

wording of their laws as the spirit or intent behind them. When large numbers

of ordinary citizens begin to see their laws as unjust, they start to seek ways

to circumvent those laws. The justice system become less and less effective.

Then, too many offenses go unpunished, a bad sign for any society.

In our work here as

students of human cultural evolution, one thing to note is that in human

history, causes and their effects can take generations to connect. A decadent

society, whose citizens no longer live by their values, deteriorates gradually

into corruption, rebellions, and anarchy. For students of History, mounds of

irrelevant trivia can obscure their view and keep them from seeing how decay in

a society’s belief system produces effects in the daily lives of its people.

Why did they win this war or lose that one? Did they fall because of this

famine? This plague? The wars, famines, and plagues are not usually the prime

causes of any civilization’s fall. The cause of a civilization’s fall is moral

decay, nearly always. When most of a nation’s people are living by their values,

it handles challenge. When its people’s values, as shown in their actions,

decline below a critical threshold, it will fall to the next hard challenge it

encounters.

But we should not be

surprised at the gradualness of the processes of History. In truth, they only

seem gradual in the limited view of the individual. A thousand years is fifty

human generations. In the terms of biological evolution, fifty generations is

trivial. In genetic evolution, a thousand generations often have to pass before

a new anatomical or physiological feature in a species can prove its usefulness.

On the other hand,

the evidence of History indicates that a new belief, with its morés attached,

even though it looks slow-acting in our eyes, can prove itself much more

rapidly than a new anatomical or physiological trait can. We can see the

workings of human cultural evolution in action if we know what to look for. For

example, Renaissance Science – with its venturesome spirit, its freeing of minds

from the superstitions of the Middle Ages, its belief in the physically-caused

nature underlying events, and its rigorous method of theory-forming and testing

– created better and better guns. For the people in those times, guns changed

everything. In one century, knights in armor were out, guns were in.

Note also that even

when it moves more slowly, the cultural kind of evolution, i.e. the human kind

of evolution, is more efficient than the genetic one used by non-human species:

cultural evolution responds to changes in the environment more quickly and

effectively than does genetic evolution. Since Enlightenment times, in fact,

humans have been getting better and better at altering Nature herself. We don't

wait for Nature to hit us with a challenge anymore; we have begun to go over to

the offense and dominate Nature much faster than we once did. Some drugs cure

diseases, but vaccines are better; they prevent diseases.

In any case, the

cause-effect connection between a human society’s ideals and its customs and

finally its success in the material world is always there for us to see if we

look hard enough. We just have to study a lot of societies and a lot of belief

systems; then we begin to notice the trends and connections between courage,

wisdom, freedom, and love and their consequences in plentiful goods, control of

disease, and military success.

Plagues, famines,

wars, etc. are readily dealt with by a society that has the values of courage,

wisdom, freedom, and love firmly in place. Natural disasters are just the

uncertainty of the universe taking physical form. These too are dealt with by

vigorous, pluralistic societies. To meet universal uncertainty at its

inception, whatever form disaster is about to take, successful societies learn

and practice courage, wisdom, freedom and love. Then the material achievements

– greater harvests, birthrates, territory, etc. – arrive.

It is also worth

pointing out here that some societies in the past even worked out sets of

beliefs and customs that enabled them to live and multiply so well that for

generations, their wealthiest citizens came to believe they had found the

answers to life. These citizens created niches that were insulated from contact

with the uncertainty and adversity of the material world; their belief in their

values deteriorated till they came to regard the values behind their comfortable

customs as quaint, old-fashioned notions.

In reality, nothing

could be further from the truth. In reality, we must deal with reality. It

keeps being hard and unpredictable, demanding courage, wisdom, freedom, and love

of all citizens if their society is going to stay strong. What can confuse an

analysis of History is that when citizens do begin to get lazy about living

their values, the crash of their society may take a while to arrive – and its

cause may be obscured by a lot of irrelevant trivia. But it will arrive.

It is also worth

noting here that the numbers of cultures possible that would qualify as brave,

smart, free, and kind is close to infinite. If we brought together all the

records from all the cultures that have ever existed, this would still give us

only a tiny fraction of the number of cultures possible. We’ll never observe in

History every possible way of adapting to catastrophe or opportunity.

Therefore, we must

search through the records of all human societies for the larger general

principles and try to accumulate what knowledge we can about how they steer our

species as it moves forward through time. Wisdom. The accumulation of knowledge

of what really works has been long, hard, and slow.

But however hard all

that reading, thinking, debating, and writing has been, as much in our own times

as in any past era, it has to be continued. From those mounds of historical

records, our minds must extract the general principles that we need to save

ourselves from ourselves.

University

of Virginia: Modern scholars

(credit:

Mmw3v, via Wikimedia Commons)

Some people in every

era don’t want to thoroughly study the past. Such studies might lead to change.

They resist change as automatically as they breathe. They want to stay with

what they were raised to because it feels secure. But if we don’t learn from

the past, if we don’t constantly strive to grow, change, and adapt to the

evolving nature of reality, then always, reality comes for us.

Change is the one

constant in this universe. This is very scary for many people. So many paths,

so many hazards. We don’t want to be this free. But we have no other

choice.

An implicit

assumption of this book is that we can’t hide from change. Thus, the one

alternative strategy is that we must go at life. Hard. Or go under.

Freedom, as a value

programmed into children, is vital to society. It drives us to develop our

talents and live motivated lives. It pushes us to handle change. But, if it

weren’t complemented with love, freedom would beget cliques, gangs, and

factions, then prejudice, violence, and anarchy.

Brotherly love, as a

widely accepted basic value, solves this dilemma for society. In Roman times,

for example, love seemed so crucial to Jesus that he told his disciples to aim

to place love above all other virtues. He said that it was the one thing he’d taught

them that they must not forget. Implicitly, he was saying all other values –

even courage and wisdom and their benefits – accrue from love.

“A new commandment I

give unto you, that ye love one another as I have loved you. By this shall

all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another.” (John

13: 34-35)

Thus, humans sustain

and spread by practicing lifestyles that may seem paradoxical to anyone who

looks for all phenomena to be reduced to simple parts. Freedom must be balanced

with love because in balancing these values in our daily lives, we mirror the

balance principle of the ecosystem of the earth. Competition and cooperation

are always in some kind of balance in every creature’s life, even for a shark.

He can’t reproduce by voraciousness alone.

This is basic systems

theory. We couldn’t survive long in this uncertain reality, as individuals or

societies, if our lives were otherwise. And the balances are tricky to find and

maintain. But who really expects easy? Freedom is a precious, beautiful thing.

If the price of it is maintaining a loving attitude and standard of respectful conduct

as we deal with our neighbors, there is a deep sense of symmetry to that

picture. A good way of life for an individual or a society takes constant work.

Attention. Adjusting. It is hard sustain. But it’s not impossible.

Therefore, we need

internal tensions in our communities. Pluralism is a sign of a vigorous

society. Monolithic, homogenous societies lack resourcefulness. A democracy may

seem to its critics to be enervated by the energy its people waste in endless

arguing. But over time, in a universe in which we can’t know what hazards may

be coming in the next day or century, diversity and debate make us strong.

Wishing to escape uncertainty and anxiety leads us away from love for our

neighbors, away from pluralism and from freedom. And love is not just “nice”:

it’s vital. It has carried us this far; it is all that may save us.

A basic Buddhist

truth is that life is hard. Another is that only love can drive out hate.

Jesus’s prime command to us all: love one another as I have loved you. These

codes have not survived because a bunch of old men said they should; they have

survived because they enable their carriers to survive. In short, our oldest,

most general values have survived in us because they work.

(by Monsiau) (credit: Wikimedia

Commons)

Now let us sum up

this chapter: courage is the human answer to entropy, the adversity of reality.

Wisdom balances courage. Freedom is the human response to uncertainty. Love

balances freedom. Diligence, responsibility, humility, and many other values

are hybrids of the four prime ones. They are not easy to see in action; they

show their value only on a huge scale as the daily actions of

millions of people over thousands of years keep evolving and keep getting, for

the followers of the best tuned values codes, better and better results.

But values are not

trivial theories or arbitrary preferences, like preferences for certain

flavours of ice cream or brands of perfume. Values are large-scale, crucial human

responses to what is real.

In the next chapter,

we shall strengthen the case for the realness of moral values by showing some

ways in which the cultural model of evolution closely parallels the biological

model of evolution, the one by which we understand life on this planet and how

it grows and changes. At that point, the case for moral realism will be proven.

Then, at last, we are

going to find that understanding how human moral values work, how they drive

behavior, and how behavior is connected to survival – i.e. understanding moral

realism – can lead us on to a form of theism.

Theism is coming,

dear reader. We are drawing near to it now. Hang in there.

Notes

1. Friedrich Wilhelm

Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, Part

XXXIV, “Self-Surpassing” (1883; Project Gutenberg). http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm#link2H_4_0004.

2. Kenelm Henry

Digby, The Broad Stone of Honour; or, The True Sense and Practice of

Chivalry, Vol. 2 (London: B. Quaritch, 1976).

3. Thomas

Carlyle, Past and Present, Chapter 11 (1843; The Literature

Network).

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.