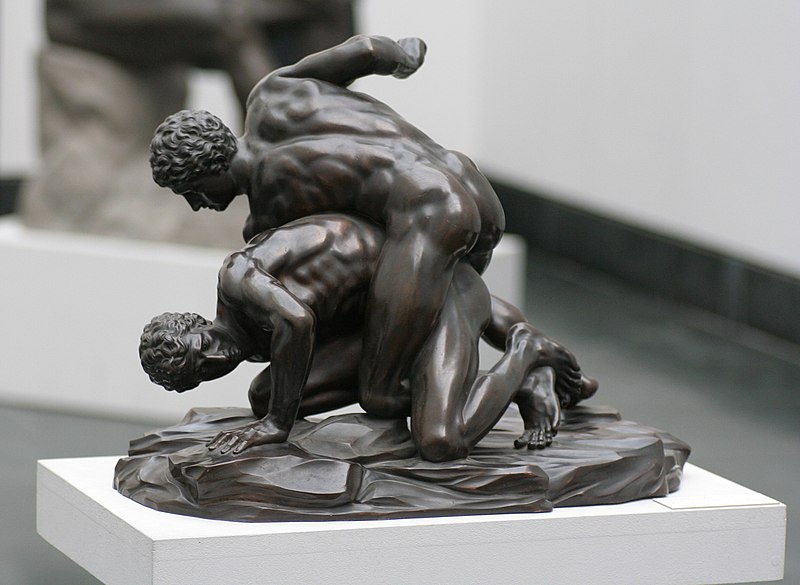

Pankration fighters (from a copy of an ancient Greek statue)

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The

Ethical View Implicit In Sport

Sports

have a great deal to teach us about all aspects of our philosophy of life, not

our claims about our philosophy, but our real philosophy of life, the one that

is implicit in the actions we do every day. And of all the components of our

philosophy, sports reveal our moral philosophy the most deeply.

At

first glance, the whole idea of a 'sport' sounds impractical. If I can win

acclaim from my family, my village, etc. by directing a ball into a goal, why

not pick up the ball and run with it until I am in front of the opposing team’s

goal, then throw it in? The joy of being applauded by my family and friends,

perhaps even my whole town, is appealing. We humans are a social species. We

like praise. So why not get that praise in any way I can? Why worry about

whether I touch that ball with my hands or not? Why care about the rules of

this game?

But

no one will applaud if I score by cheating. In fact, I will bring dishonor to

my family and my village. Cheating, breaking the rules of the game, is said to

be 'unfair'. Clearly, sports activities are programmed by complex social norms. How we play a game is controlled by what we have been taught about how the game is supposed to be played. In short, sports show our moral values in action.

Lance Armstrong, disgraced cyclist and proven cheater

(credit: McSmit, via Wikimedia Commons)

What

is this idea of 'fairness'? Why does it matter to us? We want to score goals and win races, but only in prescribed ways, it seems. Something deep in our natures is being

revealed here.

So

let’s begin by taking a long, careful look at what all sports have in common.

What makes a sport a sport.

A

sport is an activity that involves competition between two human individuals or

groups who are striving, within a set of rules, to achieve opposing objectives. They

want to score goals on us, while preventing us from scoring on them. We want

the opposite.

Each

player or team seeks to achieve their objective, i.e. to win the game, by

exercising greater control over material things than their opponents. Handle

the ball or the puck or the raquet or whatever objects the game involves with

greater skill than their opponents and so score more goals, ace more serves,

land better jumps, etc. than the opposition does, within a fixed span of time.

In

many sports, the physical 'thing' being controlled is a ball of some sort, but

it can be an object of some other kind (e.g. a puck in hockey), and it can even

be one’s body as in boxing or gymnastics or synchronized swimming. The two

parties in the competition must compete within a set of rules of the game made

available in written form to all involved long before the competition begins.

Thus,

it is competition that is not wide-open, but rather competition within a set of

guidelines dictated by the rules of the game, that makes a sport a sport.

Sergio Ramos performing a bicycle kick

(credit: Alejandro Ramos, via Wikimedia Commons)

If

a competitor is playing a sport and acting all the while within the rules, and

she/he is able to demonstrate a greater degree of mastery over things than that

being shown by her/his opponents, by scoring more goals or cleanly landed blows

or triple axels or whatever is the object of the sport, then she/he will

receive the applause of fellow players and fans. Often, a great deal of

applause.

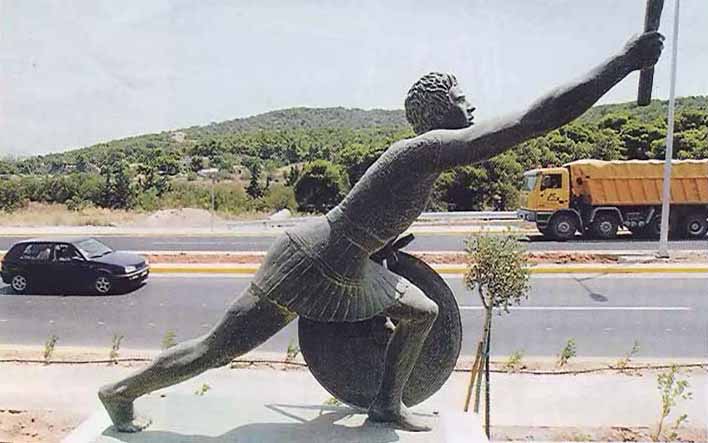

statue of Pheidippides, purported runner who carried news

of Athenian victory on Marathon plain back to Athens

(credit: Hammer of the Gods27, via Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, very

proficient athletes have been raised to hero status since ancient times.

Thousands of years ago, winners of Olympic competitions in ancient Greece were

welcomed as they returned to their home cities with parades and cheering crowds.

Sometimes, a section of the city wall was even knocked down so they could

stride in through the gap like conquerors. (Is sport a substitute for war? What

does the evidence say?)

In

addition, it is worth noting here that athletes who show, by word and action,

respect for other players, coaches, fans, and the customs, morés, and

traditions of the game bring further praise to themselves. This praise – if an

athlete exhibits a personal style that is “sportsmanlike” – will come from her

or his teammates and fans, but also from opposing fans and even opposing

players. Thus, even boxers who knock an opponent unconscious for several

seconds or minutes, can embrace their opponents after the fight. Soccer

players, tennis players, baseball players, etc. also gain praise for

themselves and their team by showing sportsmanship. The greatest of athlete-heroes

draw thousands of fans to the venues where they compete and, from the money

gained by ticket sales, are paid annual salaries ten, twenty, fifty, even a

hundred times the salary of the average fan attending the games. Clearly, people

all over the world love this idea of physical competition within a set of rules.

Sport.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/Z2I77RXLV5K4HLSP7NLFHPQHQQ.jpg)

18 yr. old Canadian soccer star Alphonso Davies

(whose playing rights have been sold for $29 million to Bayern Munich)

(credit: Robyn Beck, via the Globe and Mail)

And

all these monies are paid so that fans may watch for an hour or so as humans

perform what is essentially a frivolous activity. At the end of the game, no

food has been planted or harvested by the athletes, no clothes sewn, no

shelters built, no diseases cured, no injuries healed. In fact, athletes

regularly come out of contests injured far more than they were when the contest

began.

And

still fans applaud. Why? Because they are entertained by a demonstration, under

a set of rules, of mastery over things. Seeing mind dominating matter is exhilarating

to watch.

Now, what does sport tell us about our moral values?

First,

let’s repeat some points made in earlier posts. They can bear repetition.

All

sports assume the truth of some profound philosophical claims, the first of

these being that the reality we see is mostly as we see it. Thus, how humans

play sports reveals our ontology, our philosophy of what reality is. The ball

is real. My body is real. The two can interact in the real, physical world. That

object coming toward me is not an illusion induced by my own wishes or fears.

Secondly,

sport assumes that humans have free will. An athlete can control her body and

can, for example, strike a ball with her foot in such a way that she impels the

ball to fly rapidly toward the opposing team’s goal. So rapidly, in fact, that

the opposing team’s goalkeeper cannot reach out in time to stop the ball from

flying into the goal. Sports let us demonstrate our free will.

Canadian soccer star, Christine Sinclair

(credit: Noah Salzman, via Wikimedia Commons)

Every

person watching believes in human free will. Every viewer believes that the mind

inside that human controlled her foot and, via her foot, the soccer ball. The

ball did not fly into the netting because of the background physical forces in

the universe. The goal was not scored by entropy or quantum probability. She

did it. The 'she' that is most truly herself. She is responsible. And good for

her. Hooray for our team!!

In

the third place, we now arrive at the moral insight of sport. If we can see a

mind at work in a great play, which we can, then we can also see a mind in any action that willfully

causes injury to another player. We can judge – and more especially, trained

officials can judge – when a player intended to injure another. We admit we can’t

tell perfectly. Dirty players can make an elbow hitting an opponent’s nose look

accidental. Sometimes. But the majority of the time, because we know so well how

human bodies move, we know when we see a dirty tackle.

In

other words, we can tell when someone is responsible for an entertaining,

graceful action, and when she is responsible for a mean, vicious action, and we

can then mete out praise or blame, reward or punishment, appropriately. Reward

skill, cooperation, and respect. Punish cheating and viciousness, which are demonstrated

in attempts to surreptitiously violate the rules or to injure or both.

This is moral philosophy in action.

Thus,

we see that sports reveal our implicit belief in human free will, and also that attached inescapably to free will comes responsibility for our

actions. Freedom and responsibility are two sides of the same coin, and both are assumed in sports.

Actions

in sport that demonstrate physical skill combined with keen, winning attitude

all balanced with respect for the rules of the game and sportsmanlike play –

these are the actions we praise most highly. These are the actions that inspire

us to cheer so loudly. Humans demonstrating mastery over stuff while still

respecting the rights and dignity of other humans.

Benatio tripping Aguera in Munich vs. Man City game

(credit: Landov/Press Association Images, via the Daily Mail)

Thus, in sports, actions have consequences. Particularly

sportsmanlike players are paid huge salaries, but also given praise and

trophies for the character shown in their play.

“Fifty goals in fifty games

this hockey season. And the fewest penalty minutes of any player active in the

past year. He doubly deserves all this credit and praise. He has demonstrated

for us all, that, for a while, to an exciting degree, a human mind, via

the body it is attached to, can control ‘things’.”

And

that’s the fascination of sport. For a little while, through our sports heroes,

we rise up and defy gravity, space, matter, energy, time … and even death.

When

we play the game hard, fight a clean fight, give our all for the whole hour, we

celebrate and exult in our sometime mastery over things. And we do it while cooperating

with fellow humans, some from races, creeds, sexual orientations, and so on,

very different from our own. That is moral philosophy in action. Sports reveal

that humans really do have this capacity. We can live together and interact and

still get along.

Sports so closely mirror the human condition that they can even evolve. Coaching philosophies, skills, styles of play, sometimes even

rules – all of these change as morés and technologies change. For example, soccer balls

today are better made and are much lighter than they were fifty years ago. Why

would the governing bodies that control how the sport is played ever allow

these new kinds of balls to come into the game? Where was their respect for the

traditions of soccer?

The

new balls were taken up by the governing body of the game simply because they

made the playing of the game more exciting. The degree of mastery over ‘things’

that players can show with the lighter ball is very gratifying for fans to

watch. FIFA officials could see that, so they chose to make the change. And it

worked. Today, soccer is far and away the world’s most popular sport.

Finally,

then to sum up, I will repeat that I find it entirely reasonable to believe

that humans have free will, that they can be held responsible for their

actions, that it is feasible for other humans to hold them accountable for

those actions, and reward and praise them for skilful and moral actions and

punish them for immoral ones. And then mete out the reward or blame appropriately

nearly every time. Why do I believe these claims? Because evidence from sport supports them.

The

‘realness’ of the reality we see. Our high degree of control over that reality,

at least at our level of resolution. Our resulting capacity to be held

responsible for our actions in the real world. The idea that observed details

can reveal to an outside observer whether an action is moral or immoral. All of

these beliefs are affirmed every time the players take the field.

Sports

don’t prove beyond all possible logical challenge that any of these

philosophical claims are true. But in sports, all these claims are assumed,

provisionally, every day. Then,

those who assume them act on the assumptions.

And

they work.

What makes 'right'? Playing by the rules that you agreed to play by before the contest began. Accepting the outcome, win or lose, gracefully, then moving on.

What makes 'wrong'? Violating the rules by trying to cheat, trying to win by kinds of action that the rules forbid, especially when the violation shows to the large majority of neutral observers that an intent to injure another person, in ways that the rules forbid, was guiding that action.

Ali knocking out Foreman in Zaire, Oct. 30, 1974

(credit: Associated Press, via the Guardian)

Ali knocking out Foreman in Zaire, Oct. 30, 1974

(credit: Associated Press, via the Guardian)

Even boxers, intent on knocking each other senseless, striking each other with all the force they can muster, fight under a set of rules.

And that is what makes 'good'.

In

the shadow of the mushroom cloud, nevertheless, enjoy the game.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.