Chapter

3 Where

Moral Emptiness Leads

World War I, young German soldier

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

By

the early twentieth century, the impacts of the ideas of Darwin and Freud, and

of Science generally, had arrived. Social scientists and philosophers were left

scrambling to understand what new moral code, if any, was implied by this new

way of seeing the world. “What is Science telling us about what’s right?”

people asked. Answers on every side were contradictory and confusing. Then,

following too soon, in a bitter, perhaps inevitable irony, real-world events

broke out of control. In 1914, World War I arrived; it became the major test of

the moral systems of the vigorous, new Science-driven societies of the West.

World War I recruitment poster (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

When

World War I began, in the cities and towns of Europe and of all the other

countries attached to the main belligerents, banners flew, troops marched,

bands played, and crowds of men, women, and children all shouted for joy. A few

sober people raised objections for one set of reasons or another, but they were

drowned out in the din. In every nation involved, people fell easily into

viewing the human race as being made up of "us" and "them",

as people tend to do in wartime, and people easily began to say, even in

ordinary conversation, that the “decent armies and ideals of our way of life

are finally going to sweep aside the barbaric armies and ideals of our nation’s

enemies”.

Exhorted

in speeches by their leaders and by writers in the media to stand up for their

homelands, the men of Germany, Turkey, Austro-Hungary, Russia, France, Britain,

and Italy, along with all their allies, absorbed the jingoistic stories being

told in their theaters and newspapers. Men signed up to fight. Competing

“narratives” about Europe and its history had brought European nations into

head-on confrontation. "They" had their view of how the future should

go. "We" had a different one. Scientists said, "You're both

right.", or more often, "Don't look at us. We don’t get involved in

debates about moral rightness." The only way left to resolve the

dispute was to fight it out.

Anti-German

propaganda poster (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

My

country, Canada, was part of the British Empire in 1914, and Canadians were

just as eager as any of the loyal subjects in London, England. Young men leaped

out of the crowds lining the streets to march in step with the parades of

soldiers going by. Many of them were worried that by the time they got through

their training and over to Europe, the fighting would be done. Girls clustered

around men in uniform who came back to visit their workplaces or colleges or

even high schools before shipping out. Old ladies out shopping, by 1916, would

spit on any young man of military age who was not in uniform.

Long before the horrible

casualties began to mount, World War I was huge in the views of the historians

even from its very beginning because, for the first time in history, modern

scientific weapons and technologies were going to be used to kill men in

assembly-line style. The process was going to be made as efficient as the new

factories. Scientifically-tested technologies, arranged in efficient sequences,

supervised by experts, would be set up to kill human beings. (“To end the war”,

the leaders said.) Now we would see what Science could do.

We saw.

Consider just one telling

statistic: the British Army casualties on the first day of the Battle of the

Somme were 60,000 – 20,000 of whom were killed. Actually, in about five hours.

France, Russia, Germany, Austria, Italy, the U.S., and all other countries

involved eventually suffered similar losses, for four long years.

In the end, nine million

combatants were dead, with three times that many permanently scarred. And those

were just the combatants. How many civilians? No one really knows. Every

country on Earth was touched, or we should say wrenched, either directly or

indirectly. Over six hundred thousand Canadians (from a population of eight

million) enlisted in the armed forces, and out of the four hundred twenty

thousand who actually got into the fighting in Europe, over sixty-five thousand

died.

Commentators writing in

newspapers and magazines in the last months leading up to WWI had discussed in

total seriousness the very likely possibility that the new modern weapons would

be useless because men would simply refuse to use them on other men. Modern

torpedoes, flame throwers, machine guns, poison gas, airplanes – and the

horrors they’d cause! No. No one would really use them.

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

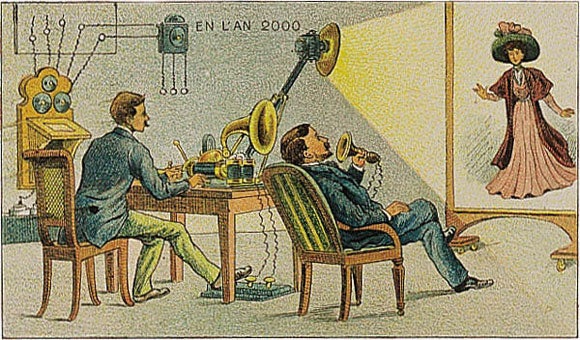

Other writers a few years

before, more hopeful about how Science would affect society, had even been

speaking of a coming Golden Age. Science wasn’t just showing us how to build

horrible weapons. It was also curing diseases, creating labour-saving machines,

improving agriculture, and even inventing new forms of entertainment. Progress

was steadily reaching into the lives of even the humblest citizens. Surely,

goodness and mercy would follow close behind.

The First World War

shattered the optimism of the Golden Age prophets, but it also shattered much

more deeply the confidence of the nations of the West, which had begun to

believe that they had found the answers to life’s riddles. Pre-WWI, people in

the West had come to believe that their wise men were in control: the ways of

the West, with Science to lead them, were taking over the world, and thus the

sufferings of the past would be gradually reduced until they became only dim

memories recorded in books.

There had been wars and

famines and depressions before, but the traditional ideas of God and of right and

wrong, based on the Bible, had retained the loyalties of people in the West

because: first, the damage had been minor compared to that caused by WWI;

second, the ways of the West had, for the most part, seemed to work; and third,

there hadn’t been a serious alternative set of beliefs to consider.

But now, with the rise of

Science, all was changing. As we gained physical power, our ideas about how to

handle all that power began to seem increasingly inadequate. Then, in the

horrors of WWI, the moral systems of the Western societies seemed not just to

fail but to unravel; people’s worst fears came true. The “guys at the top” were

fools. Science was a monster, and it was on the loose.

Science was providing new

communications technologies that were giving the xenophobic, tribalistic forces

and leaders in Western societies more power to mold people’s minds. It was also

arming these forces and leaders with ever bigger and more terrible weapons –

while the moral philosophers and social scientists dithered about what “right”

was and what we “should” be doing. The outcome had a feeling of inevitability

to it. An arms race became normal. Bigger warships, cannons. Weapons ever more

effective. Poison gas. Flame throwers. The odds of the war

starting kept rising. Sooner or later, it had to happen.

Standard

German soldier’s belt buckle (WWI (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Descartes’ method, using

Christian morals to control scientific technologies, wasn’t working. Not only

were Christians doing unthinkable horrors, they were doing those horrors mostly

to one another. Worst of all, in every one of the warring nations, these acts

were being done expressly in the name of their God. Gott mit uns was

embossed on nearly every German soldier’s belt buckle. “Onward Christian Soldiers”

was sung at church services in nearly every English-speaking country in the

world.

In the meantime, by the

end of the fighting, the political, religious, and business leaders in every

sector of society appeared to be out of answers. Most of the victors continued

to spout the platitudes that had got their nations into the horror to begin with.

To thoughtful observers, Western moral systems looked bankrupt. Paralyzing

doubt began to haunt people in every level of society, from the rich and

powerful to the middle classes to the poor.

If the morals of the West

had led to this, people could not help but think, maybe Science was right about

the Bible. Maybe the moral beliefs that it recommended had all been a fraud.

Maybe there were no moral rules at all. Disputes must always be settled by

violence. Darwin’s model of the living world had portrayed “nature red in tooth

and claw.” It seemed to be the final word. Survival of the fittest: wolves kill

deer, spiders kill flies, big fish kill little fish. This seemed to be the only

credible model left. Mere anarchy was loosed upon the world.

For millions, the old

moral code was done. Obsolete. It didn't work. It had led the world to

"this". The only viable alternative people had to look to – Science –

flatly refused to say anything about what right and wrong were.

Before the scientific

revolution began to erode God out of the thinking of the citizens in the West,

even if people hadn’t been able to grasp why bad things sometimes happened in

the world or why bad people sometimes got ahead in spite of, and even because

of, the suffering they inflicted on others, people could still believe God had

reasons and the code of right and wrong still held. God was watching. Matters

would be sorted out in time. The liars, thieves, bullies, and killers would get

their just deserts in time. We just had to be patient and have faith. The

people, in large majority, believed the authorities’ official spiel.

But World War I was just

too big. With the scale of the destruction, the pathetic reasons given to

justify it, and the amorality of Science gnawing at their belief systems,

people began to suspect and fear that, just as Science had said, there was no

God, the Bible was a set of myths, their leaders were a bunch of deluded

incompetents, and the old moral system was a sham. And then, things got worse.

British

bulldozer burying bodies at Belsen (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

British soldiers forcing German concentration camp guards to load bodies

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

Following the First

World War, to exacerbate the moral confusion and despair, the man-made horrors

of the twentieth century began to mount. They are many and ugly. The Russian

Revolution and Civil War. Many other smaller wars. The worldwide Depression.

World War II, six times as destructive as World War I. Hitler’s camps. Stalin’s

camps. But we don’t need to describe any more. The point is that these were the

actions of a species that, by its science, had gained great physical power at

the same time as it lost its moral compass.

The big question,

“What’s right?” keeps echoing, and the big fears that go with it keep growing.

Where will the code that we need to guide our behavior in business,

international affairs, or even everyday life come from now?

Of course, there are

the cynics, the ones who say that they don’t know or care whether we ever find

a way to set up universal standards of right and wrong. They see the pursuit of

a universal moral code as a futile waste of time.

But

whether they focus on daily human lives or on History’s big trends, or their

focus is somewhere in between those limits, I tell these cynics, “If you really

thought that way, we wouldn’t be having this debate. You wouldn’t be here.”

Albert

Camus, French philosopher (1913–1960)

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

As

Albert Camus sees it, suicide is the sincerest of all acts.1 Its

only equal in sincerity is the living of a genuine life. A genuine person stays

on in this world by conscious choice, not by inertia. A genuine person has

created a vision of the world and how she/he can live with purpose and meaning

in it, and so is still here because she chooses to be, even when, especially

when, she knows the life she will live will be full of hardship. The sincere

have guts.

Insincere people may claim to be alienated from this world and the other people in it, but that simply can’t be the case if they are still alive and talking. These people are only partitioning up their minds, for the time being, into manageable compartments of cynicism. But the disillusionment they feel now – on any matter, personal to global – is going to seem minor compared with that which they will one day feel for themselves, one day when their mental partitions begin to give way. And it doesn’t have to be that way, as we shall see.

So,

to sum up our case so far, what have we shown?

First,

that Science has severely eroded the old beliefs in God and, thus, the old

moral codes. And it continues to do so.

Second,

that Science has refused, and continues to refuse, to take responsibility for

the gap it has made. It has insisted adamantly for decades that it has

nothing to tell us about which of our actions are right or wrong.

But,

thirdly, due to our ongoing need just to manage our lives and, more

importantly, the power Science has put into our hands, we must replace

the moral code we no longer believe in with one we do believe

in. Perhaps then we will have a chance to get past our present peril.

In

short, Science’s refusal to tell us anything about what our moral code ought to

say is not good enough. Period. We have to find a code of behavior that will

give us a way of life, one that makes “right” consistent with “real”.

If

we can work out a moral code that we truly believe in, because we see solid

reasons and objective, replicable evidence that show it is congruent with

reality, will it lead us on to belief in a Supreme Being? Or, in short, can a

case based in Science lead us to a new code of decency that then leads us on to

belief in God?

That

question I will set aside for now. Let’s aim first to find a moral code that’s

based in physical reality. A scientifically sound model of what “right” is.

As

promised, I will deal with the Supreme Being question in the last chapters of

this book. But for now, let us try to confront and quell “the worst” among us.

Notes

(Harmondsworth,

UK: Penguin Books, 1975), p. 11.