Chapter 2 – The Moral Emptiness

Of Science

William Butler Yeats (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Things fall apart; the

centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed

upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is

loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence

is drowned;

The best lack all

conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate

intensity.

—from “The Second Coming”

by W.B. Yeats, 1919

When our idea of God

began to erode, so did our ideas of right and wrong, and when those ideas began

to erode, we became the society that Yeats described in his great poem “The

Second Coming”. We live in a time in which some of the most immoral of citizens

are filled with “passionate intensity”: fraudsters claim they are daring entrepreneurs;

Mafia thugs claim that they are just soldiers in one more kind of war;

warmonger generals tout their own indispensability. In short, these people see

themselves as moral, even heroic, beings.

In the meantime, some of

what should be society’s most moral citizens “lack all conviction.” For

example, it would seem logical that people looking for moral direction in the

Science-driven countries of the West would turn to their gurus, i.e.

scientists. Especially those who study human societies and the moral beliefs they

run by. In the West, these experts are our anthropologists and sociologists.

Trained to make astute, Science-based judgments about human societies and

their “ways of life”, social scientists should be our most morally gifted

citizens.

But social scientists in

the West have no moral directions to offer their fellow citizens. In their

writings, they flatly deny that moral values refer to anything real at all. American

anthropologist Ruth Benedict put it succinctly: “Morality differs in every

society and is a convenient term for socially approved habits.”1 Thus,

as moral guides, Science and scientists – social scientists, in particular –

appear to be pretty close to useless.

How can this be? How can

highly intelligent people who set as their life purpose a full comprehension of

why humans in groups behave in the ways that they do – and who engage in years

of study and research intended to bring them to that goal – how can they then

tell us that the moral codes all people learn as children, and consult to guide

their behavior, their choices, and actions every day, are all hollow, devoid of

content? This picture defies sense. If social scientists aren’t working to

understand why groups of humans act as they do, what are they doing? If

humans’ stated moral codes are unrelated to their actions, even though they say

those codes are what guide their actions, then why do all those people – observed

and observers – talk about their moral sentiments at all? Is it all verbal

“grooming behavior” that does nothing but fill idle time?

But in response to

questions about what moral codes are, and how they relate to humans’ real

actions, most social scientists, as noted above, say their studies have led

them to conclude that moral codes have no grounding in the real world. Moral

claims are just expressions of tastes, like a preference for one brand of

perfume or flavor of ice cream over its competitors. Statements about “right”

and “wrong” are just ways of venting emotion. “Right” and “wrong” are empty

concepts, unrelated to any empirical facts. These experts then challenge their opponents

to prove otherwise.

Many even go over to the

offence and ask what it is that all Science is seeking. Are scientists seeking

truth about reality? That, by pure Logic, is unattainable. But, if not truth,

sociologists ask, then what is Science seeking? The answers to these questions

are parts of a fight going on in universities worldwide right now.

Thomas Kuhn’s The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions is arguably the most influential work on

this topic. In it, he casts a dark shadow over Science’s view of itself.

He argues that in reality all branches of Science move forward via processes that are not rational. The

scientific method is driven by intuition, not logic. Science does not progress

by a steady march of improving knowledge; it moves from less useful pictures of

reality to more useful ones by unpredictable leaps that he calls paradigm

shifts.

A paradigm shift occurs in

a branch of Science when many individuals in that branch, separately, each have

a moment of insight and then experience a leap of understanding so profound that

it makes them literally see reality in a new way. But they cannot tell you

after their cognitive leap has occurred how it came to pass, and they then came

to grasp this new picture of the world.

Scientists who grasp a

paradigm shift do indeed come to “see” the world in a totally new way because

their minds then have been reprogrammed to see different patterns in the details

around them. That’s how profoundly the new model, once they learn it, affects

them. Each scientist who “gets it” experiences a kind of “conversion” that

steers her/him into a community of fellow believers.

In all branches of

Science, Kuhn claims, old ways of thinking are dropped, and new models become

accepted ones via this process that appears to be driven at least as much by non-rational

mental processes as by rational steps like theorize, test, and repeat.

Clearly, the modes of thinking that enable Science to evolve run deeper than

reasoning and evidence can explain. Kuhn gives many examples from the History

of Science to support his case. His work has evoked many responses, pro and con,

but there is no doubt that he has shone a troubling light on the reliability of

all of Science.2 In short, Science is not done scientifically.

In the meantime, counterattacks

aimed back at the social sciences are made by critics like philosopher John

Searle. He admires the physical sciences because, he claims, they can be logically

rigorous. Physical sciences describe their theories and the studies designed to

test them using unambiguous terms. (One calorie heats one gram of water one

Celsius degree.) But the social sciences use models that are too vague to

support rigorous reasoning. (In Anthropology, what makes a “big man”?) Thus, conclusions

reached in social science are not reliable.3 (Critics of social

science are well countered in Harold Kincaid’s Philosophical Foundations of

the Social Sciences.4)

Clash of cultures: skulls of buffalo shot

by U.S. government hunters, 1880’s

(credit: Wikimedia

Commons)

In response to the

criticisms of the “unscientificness” of their discipline, some social

scientists have tried hard to be more rigorous in their work. However, many

have admitted Searle is at least partly right. For example, studies done in Anthropology

are usually difficult to replicate for a whole array of reasons. Thus, careful

checking and re-testing theories in social science is not possible.

Here let’s recall that,

in order to qualify as “scientific”, a model or theory must be testable in the

real world, and the tests must be replicable. If the tests can’t be replicated,

the theory is not Science. Tell me how you test your theory. Then, I can check

it by doing those tests myself. Easy to do in Physics and Chemistry where

materials and pieces of apparatus are standardized. All but impossible in Sociology

and Anthropology.

Many factors other than its

vague terms make social science’s studies hard to replicate.

First, background

conditions of studies in social science often can’t be reset. Socially relevant

facts keep changing. For example, how could a tribe return to living as fishers

if the species they once caught off their coasts are gone?

In social science, we also

accept implicitly that, even when conditions in the world can be “reset”, that no

custom should ever be forced on a tribe. For example, trying to get a tribe to

go back to living naked once they have chosen to wear clothes would be

unethical. Tribes in the Amazon, once they join a society where clothes are

worn, don’t want to live naked anymore. Cultural anthropologists would not try

to make these people go back to living naked, as they had been living just a

few years before. The anthropologists’ own moral code tells them that trying to

“guide” changes in a tribe’s way of life to aid research – or for any other

purpose – is wrong. Social scientists are ethically bound to observe societies

as they live, but never to interfere in their changes.

In addition, a

researcher’s own biases influence what she looks for and how she sees it. These

biases are impossible to avoid, no matter how carefully the studies are

designed. People of the Amazon see trails of peccary or cayman in

crushed grasses. But Western anthropologists see details they have been

programmed to notice (e.g. flowers, insects). An anthropologist living with an

Amazon tribe needs years of training before she can learn to track peccaries.

Finally, a social

scientist’s watching a tribe of people also changes what is being watched,

namely the morés of those people. For example, an anthropologist in the field usually

can’t work without shoes. Often in only weeks, the folk she’s living with and

studying, if they have been living barefoot, start to want shoes.

For all of these reasons

then, social scientists admit they often must settle for what is really a

single occurrence of the social phenomenon they wish to study. One that can’t

be replicated. But no generalizations can be drawn from a single, unrepeatable

instance of anything. That’s a direct contradiction of what the word “generalize”

means.

These difficulties with social

science research put us in a logical quandary.

Societies vary widely in

their beliefs and morés, and those morés keep changing even while

scientists are studying them. There are many human tribes to study, and each contains

many customs that are changing all the time. Social scientists will never adequately

document all the societies of the world as they are now.

Thus, we’ll never arrive

at any useful conclusions in social science unless we can first propose larger,

more generic theories of how human societies work.

In fact, social

scientists see that kind of plan as being immoral from its outset because it

amounts to Europeans imposing their ways on other cultures. In the meantime, critics

of social science say such a grand theory can’t be formulated. They insist

absolutely that social science is too vague, from its terms on up, to ever

enable its practitioners to create a general theory of how societies work.

If such a theory ever were

articulated, it would give direction and focus to all social science work. Under

it, social scientists could propose and test specific hypotheses. But until

social science has a comprehensive theory to guide its research, it will remain

what Ernest Rutherford dismissively called “stamp collecting”: people recording

data but making no attempt to explain them.

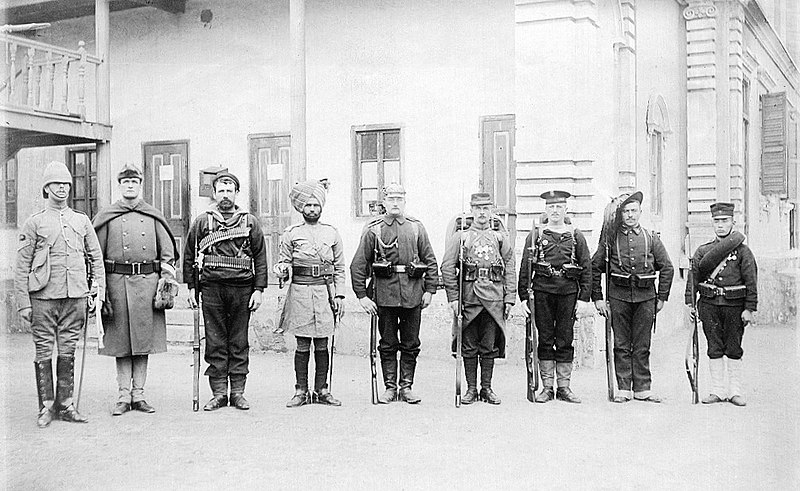

Cooperation of cultures:

soldiers of the 8 nations alliance during

the Boxer Rebellion in China, 1900

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

At this point, some social

scientists’ respond to their critics with further, more aggressive counterattacks

of their own. They argue that no science, not Physics itself, is “objective”.

Culturally-slanted biases shape all human thinking – even the thinking of

physicists. For example, over a century ago Western physicists postulated, and went

looking for, what they called “atoms”, because early in Western history, a

philosopher named “Democritus” had postulated the idea of that the world is

made of atoms. Once instruments capable of reaching into very tiny levels of

matter became available, Westerners had already available the concept that

enabled them to imagine and set up experiments at that level. It had been

planted there during the educations they acquired in their cultures. But Democritus

did not derive the idea of the atom from observations of any “atoms”. The idea

was purely a product of his speculative imagination.

Thus, these social scientists

argue that the overarching view called relativism is the only

logical one to adopt when we study the body of social science research (or all

research in all fields, for that matter). We can try to observe human societies

and the belief systems they instill in their members (Western science being

just one example of a belief system), but we can’t pretend to do the work

objectively. We come to it with eyes already programmed to notice in the

details around us the patterns we consider “significant”. We see as we do

because of the beliefs we absorbed as children. Every scientist’s model of what

the world is lies deeper than her/his ability to articulate thoughts or

even just observe. Cultural biases can’t be suspended; they prefigure our

ability to think at all.

The whole of reality is

much more detailed and complex than the set of sights, sounds, etc. any one of

us is paying attention to. Other folk from other cultures notice different

details and construct their own pictures of reality, some of them radically

different from ours, but still quite workable.

In short, any human view of

the world, and especially any culture-wide model believed and used by any human

society, is inherently biased. This is the stance taken by the most adamant of

social scientists: even Physics is made of opinions.

Some social scientists go

so far as to claim there aren’t really any “facts” in any of our descriptions of

past events or even of events happening around us. There are only various sets

of details noticed by some of us; these are filtered by values and concepts we

learned as children. Within each culture, people group these details to form a “narrative”.

But as we go from culture to culture, we see that any one of these various

narratives is as valid as any other.

So, at the level of large

generalizations about what “right” and “wrong” are, social scientists not only

have nothing to say, they insist that nothing objectively true can be

said. “Science” is just a Euro-based set of theories that seem to work most of

the time. For now.

Scientists in the

sciences other than the social ones continue to assert there is an empirical,

material reality out there that is common for us all and Science is the most

reliable way we have to understand that reality. But in all branches of Science,

scientists admit that they can’t give a very good explanation or model of what

“right” and “wrong” are – if such things can even be said to exist.

In a further rebuttal of

relativism, however, scientists in the hard sciences and life sciences assert

that the idea that Science can’t give us any reliable insights into how any parts of the world work is nonsense.

Science works. Its successes have been so large and so many that no sane person

can doubt that claim.

In this complex picture

lies the dilemma of the West in modern times. Back and forth, these arguments

called the Science Wars continue

to rage. I’ve touched on a few of them, but there’s not enough space here to go

into even five percent of the whole controversy.

So what’s the bottom

line? The point of all the discussion so far in this chapter?

The point is that Yeats

was right: the best really can lack all conviction. They can even reject the

whole idea of anyone having any “moral convictions” ever. Thus, many social

scientists can read about customs like honor killings and remark, “Well,

that’s their culture.” In fact, for many thinkers today in the universities,

all convictions are temporary and local. (A more sensible compromise position

is taken by Harris in Theories of Culture in Postmodern Times.5)

This has been the

scariest consequence of the rise of Science: moral confusion and indecision in

first, our intellectual elites, then, the whole of Western society. This

confusion began to become serious in the West in the nineteenth century, after

Darwin and the granddaddy of all relativists, Nietzsche. But here we are in the

twenty-first century, and the crisis of moral confidence is getting worse. No educated

person in the West wants to say what “right” is anymore.

Now, all of this

still may sound far removed from the lives of ordinary folk, but the truth is that

relativism’s effect on ordinary people’s lives is crucial. When a society’s

sages can’t guide its people, the people look elsewhere for moral leaders. When

the wise respond to their fellow citizens’ queries about morality with jargon

and equivocation, others – some very unwise – move in to fill the demand in the

ideas marketplace.

So, now we must ask:

how has this moral paralysis since Darwin and Freud affected ordinary folk? How

has the eroding of our old moral codes affected real people’s lives? What consequences

did people who lived in the morally emptiness of the last hundred years have to

endure?

Notes

1. Ruth

Benedict, “Anthropology and the Abnormal,” Journal of General

Psychology, 10 (1934).

2. Thomas Kuhn, The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 3rd ed., 1996).

3. John Searle, Minds,

Brains and Science (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984).

4. Harold

Kincaid, Philosophical Foundations of the Social Sciences: Analyzing

Controversies in Social Research, (New York, NY: Cambridge University

Press, 1996).

5. Marvin

Harris, Theories of Culture in Postmodern Times (Walnut Creek,

CA: AltaMira Press, 1999).

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.