Chapter 20 The Theistic Bottom Line

The three large

principles summed up in the previous chapter are enough: the universe is coherent, conscious, and compassionate. Having established

them, we have enough to conclude that a higher power or consciousness exists in

our material universe. Or rather, as was promised in the introduction, we have

enough to conclude that belief in God is a rational choice for an informed

modern human being to make, a rational gamble to take.

And that is the

point. Belief in God is a choice. It is simply a more rational choice than its

alternatives, and it arises naturally once we understand all branches of Science and then see that moral values are integral parts of the overall worldview of Science. Our values are grounded in observable, empirical reality. That trait of any claim makes it into what we call "Science". Seeing that values are real is the key step that enables us to cross the line from agnosticism to theism.

But now in this chapter we begin to examine many pieces of supporting argument and evidence that give this case for theism a sense of both universality - it fits the facts of reality in so many subtle ways - and immediacy - it speaks to every one of us in ways that feel personal. Heartfelt, as a belief must if it is to endure. Each of its carriers must care about it if it is to be transmitted to the next generation.

But now in this chapter we begin to examine many pieces of supporting argument and evidence that give this case for theism a sense of both universality - it fits the facts of reality in so many subtle ways - and immediacy - it speaks to every one of us in ways that feel personal. Heartfelt, as a belief must if it is to endure. Each of its carriers must care about it if it is to be transmitted to the next generation.

At this stage of our discussion, it is also worth

reiterating two points made earlier: first, we must have a moral

program in our heads to function at all; second, the one we’ve inherited from

the past is dangerously out-of-date.

But all of this chapter so far has just summed up the case we have already made.

But all of this chapter so far has just summed up the case we have already made.

I can now give a more informal explanation of the pieces of argument we have assembled,

then add some more pieces whose special significance in this discussion will

be explained as we go along. We will make the case personal and also try to answer some of the most likely

reactions to the whole book.

Let's get more deeply into this last chapter

by revisiting, in a more personal way, a vexing problem in Philosophy mentioned

in Chapter 4, a problem that is nearly three hundred years old. The solution to

this problem drives home our first main point on the final stretch of the

thinking that leads to theism. Even though it is a gamble to believe

the universe is a single conscious system, it is a rational gamble.

Many scientists claim

that Science, unlike all the branches of human knowledge that came before the

rise of Science, does not have any basic assumptions at its foundation and that

it is instead built from the ground up on merely observing reality, forming

theories, designing research, doing experiments, checking the results against one’s

theories, and then doing more hypothesizing, research, and so on. Under this

view, Science has no need of foundational assumptions in the way that, say,

Philosophy or Euclidean Geometry do. Science is founded only on hard,

observable facts, they claim.

But in this claim, as

has been pointed out by thinkers like Nicholas Maxwell, the scientists are

wrong.1 Science rests on some assumptions that are extremely basic,

ones that may seem indisputably obvious, but that are still assumptions.

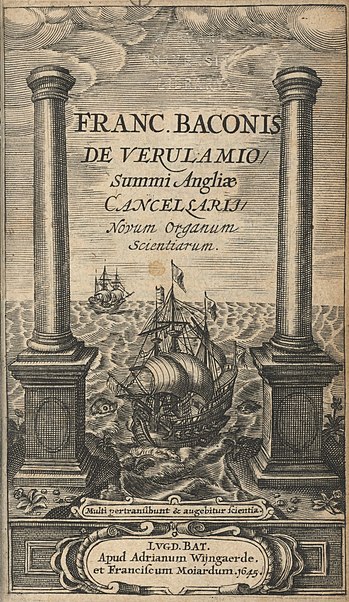

The book that told the world how Science should work:

Cover of early copy of Novum Organum

Cover of early copy of Novum Organum

(credit: John P.

McCaskey, via Wikimedia Commons)

The heart of the

matter, then, is the inductive method normally associated with Science. The way

in which scientists can come upon a phenomenon they cannot explain by any of

their current theories, devise a new theory that tries to explain the

phenomenon, test the theory by doing experiments in the real world, and keep

going back and forth from theory to experiment, adjusting and refining – this

is the way of gaining knowledge called the scientific method. It

has led us to many powerful insights and technologies.

But as David Hume

famously proved, the logic this method is built on is not perfect. Any natural

law we try to state as a way of describing our observations of reality is a

gamble, one that may seem to summarize and bring order to whole files of experiences, but a gamble, nonetheless.

A natural law

statement is a scientist’s claim about what he thinks is going to happen in

specific future circumstances. But every natural law proposed is taking for

granted a deep first assumption about the real world. Every natural law

statement rests on the assumption that events in the future will continue to

steadily follow the patterns we have been able to spot in the events in the

past. But we simply can’t know whether this assumption is true. We haven’t been

to the future. Thus, we must allow for the possibility that at any time, we may

come on new data that stymie our best theories. Thus, we must accept that

every natural law statement, no matter how well it seems to fit real data, is a gamble. It gambles on the belief that the

future will go like the past.

Albert Michelson (credit: Bunzil,

via Wikimedia Commons)

Edward Morley

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Science is

open to making mistakes. For scientists themselves, a shocking example of such

a mistake was a mistake in Physics. Newton’s model of how gravity and

acceleration work was excellent, but it wasn’t telling the full story of what

goes on in the universe. After two centuries of taking Newton’s equations as

their gospel, physicists were stunned by the experiment done by Albert

Michelson and Edward Morley in 1887. In essence, it showed that Newton’s laws

were not adequate to explain all of what was really going on, especially at

very high speeds with very large masses.

Einstein’s pondering

these new data is what led him to the Theory of Relativity. But first came

Michelson and Morley’s experiment, which showed that the scientific method, and

Newton, were not infallible.

Newton was not proved

totally wrong, but his laws were shown to be only approximations, accurate only

for smaller masses at slow speeds. As the masses and speeds become very large,

Newton’s laws become less useful for predicting what is going to happen next.

Nevertheless, it was

a scientist, Einstein, doing science who found the limitations of the theories

and models specified by an earlier scientist. Newton was not amended by a

clergyman or a hermit or a reading from an ancient holy text.

Thus, from the

personal standpoint, I have always believed, I still believe, and I’m confident

I always will believe that the universe is consistent, that it runs by laws

that will be the same in 2525 as they are now, even though we don’t understand

all of them yet. Yes, the future, not in every detail, but in the big ways, will

go like the past. My choice to gamble on Science is a good Bayesian gamble, preferable to any

of the superstitious alternatives.

As a believer in

Science, I also choose to gamble on the power of human minds, sometimes alone,

sometimes in cooperation with other minds, to see through the layers of

irrelevant, trivial events and spot the patterns that underlie the larger patterns in very large sets of data. We can figure this place out and gradually get more and more

power to move about in it without getting hurt or killed.

The alternative to

believing in the power of human minds – individually or in cooperating groups –

to figure out the laws which underlie reality is to abandon reason and instead

gamble on forming our beliefs around something other than observations of

facts. Once again, we have the evidence of centuries of history to look back

on. All the evidence we have about what life was like for the cowed, superstitious

tribes of the past suggests that their lives were – as Hobbes puts it – poor,

nasty, brutish, and short. People who were willing to think about the real world they could observe, experiment with it, and

learn from it made the society we enjoy today. Even the most obstinate of Luddite

cynics who claim to despise modernity don’t like to go two days without a shower.

My first point on this path to a personal kind of theism, then, is that belief in the consistency

of Science – i.e. of the laws of the universe and the power of human minds to

figure them out – amounts to a kind of faith. Yes, faith. Belief in ideas that

are so basic that they cannot be proved by some other more basic ideas. For

Science, there are no ideas more basic than the ones that say the

universe is a single, coherent system and that we humans can figure out how

that system works. The rest of Science rests on those assumptions.

Atheists say these

beliefs can’t be called “faith” at all. They certainly don't lead to a belief

in God. They just enable atheists and theists alike to keep doing Science. To share ideas, theories, models, and research in their branch of Science with

anyone else who is interested. But I insist they are beliefs in the long-term

consistency of concepts that can’t be seen. And that is a kind of faith.

Now let’s add some

other powerful ideas to this personal case for theism.

If we truly believe

in Science, then we are committed to integrating into our thinking all

well-supported theories in any of the branches of Science. In the twenty-first

century, that means we must try to integrate uncertainty, quantum and

non-quantum, into our world view.

Earlier we saw that extrapolating from the quantum model led us to conclude that the values we call freedom and love are real in the sense that our believing in these values leads to observable changes in our patterns of behavior. When we believe in freedom and love, the evidence says, we act in ways that improve the odds of the long-term survival of our way of life.

Earlier we saw that extrapolating from the quantum model led us to conclude that the values we call freedom and love are real in the sense that our believing in these values leads to observable changes in our patterns of behavior. When we believe in freedom and love, the evidence says, we act in ways that improve the odds of the long-term survival of our way of life.

Our ancestors lived

by the values implicit in the quantum worldview, the free will view of reality,

centuries before there was ever any scientific research to show us that the

universe is founded on probabilities, rather than on Newtonian chains of cause

and effect. But we now have a model supported by scientific research, namely

the quantum model, to fit together with our long-standing moral code that recommends

brotherly love. From Physics, we get quantum uncertainty, and from Moral

Science, freedom and love. Quantum Theory supports Moral Science, the view that

freedom and love are real, and vice versa; the concepts fit together; they

fit human minds and cultures into physical reality as Science shows it to us. Both separately and taken together, they make up a sensible gamble.

Erwin Schrodinger (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

However, the quantum worldview,

if we choose to believe in it and follow it, comes with some startling

corollaries. Quantum entanglement theory (and experiment) has shown us that particles all over the universe are in communication with each other, instantly, all of the time. This model implies that the universe feels itself, all

over, all at once.

The universe is not, as pre-quantum science pictured it, totally Newtonian and local. It is capable of what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance,”; in fact, it works that way all the time.5 Quantum physicist Erwin Schrodinger said: “There seems to be no way of stopping [entanglement] until the whole universe is part of a stupendous entanglement state.”6

The universe is not, as pre-quantum science pictured it, totally Newtonian and local. It is capable of what Einstein called “spooky action at a distance,”; in fact, it works that way all the time.5 Quantum physicist Erwin Schrodinger said: “There seems to be no way of stopping [entanglement] until the whole universe is part of a stupendous entanglement state.”6

Why does the quantum view matter so much to our case for theism? Because if we think distant parts of an entity are in touch with one another (in the case of the universe, instantly), it is entirely reasonable to further postulate that there must be an entity of some kind connecting the stimulus spin-change of one particle to the response spin-change of another particle in a distant location.

The universe is a single, coherent entity that -- apparently -- feels.

This way of seeing

the universe as having a kind of awareness is my second big idea in the final, personal stage of my argument. It is well known to scientists, theist and atheist alike.

They admit that understanding entanglement does move us a bit closer to

believing that some sort of a God may exist.

Murray Gell-Mann, Nobel Prize–winning physicist

(credit: Wikipedia)

But according to science-minded

atheists, these ideas -- about how the universe is a single consistent entity and

how it seems to have a kind of awareness -- even taken together, only add up to a

trivial belief. A proposal we can consider, but then drop because there is too little evidence to support it and, in addition, it leads

nowhere. It does not enable human minds to imagine any new models of reality, nor to any useful ways of real-world testing to see whether such new models are even, in any way, possible. Murray Gell-Mann, another modern physicist, went so far as to derisively call this whole way of thinking “quantum flapdoodle.”7

In other words, we

may have deep feelings of wonder when we see how vast and intricate the

universe is – far more amazing, by the way, than any religion of past societies

made it seem. Our intuition may even suggest that for information to go

instantaneously from one particle in one part of the universe to another

particle in another vastly separated part, a controlling consciousness of some

kind must be joining the two. But these feelings, the atheists say, don’t

change anything. The God that theists describe -- according to all the evidence -- doesn’t answer prayer, doesn’t grant us another existence after we die, doesn’t

perform miracles, and doesn’t care a hoot about us or how we behave.

Pierre-Simon de Laplace

(credit: James Posselwhite, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the atheist view,

believing in such a God is simply excess baggage. It is a belief that we might

enjoy clinging to as children, but it is extra, unjustified weight that only

encumbers the active thinking and living we need to practice if we wish to keep

expanding our knowledge and living in society as responsible adults. Theism,

the atheists say, hobbles both Science and common sense. Or as Laplace famously

told Napoleon, “Monsieur, I have no need of that hypothesis.”

William of Occam, English

philosopher and theologian

(credit: Andrea di Bonaiuto,

via Wikimedia Commons)

Centuries ago,

William of Occam said the best explanation for any phenomenon is the simplest

one that will do the job. Newton reiterated the point: “We are to admit no more

causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain

their appearances.”8 If we can explain a phenomenon by using

two basic concepts instead of three or four, we should choose the two-pronged

tool.

According to

atheists, belief in God – or at least in a God that might or might not exist in

this coherent, entangled, apparently self-aware, material universe – is a piece of

unneeded, dead weight. In our time, under the worldview of modern Science, the

idea has no useful content. It can and should be dropped. Or as the sternest atheists

put it, it is time that humanity grew up.

Starry Night at La Silla

Observatory, Chile

(credit: ESO/H. Dahle, via Wikimedia

Commons)

The model of cultural evolution developed in this book cancels the cynicism

of the atheists. Under moral realism, values are real, humanity is going

somewhere, and whether we behave morally or immorally does matter, not just to

us in our limited frames of reference, but to that consciousness that underlies

the universe. That presence, over millennia, helps the good to thrive by

maintaining a reality in which there are lots of free choices and chances to

learn, but also a long-term advantage to those who strive every day to perform actions that

balance courage, wisdom, freedom, and brotherly love.

This is the third big

idea in my overall case for theism: moral realism. First, we see the universe

as a consistent, coherent system; second, we see it as conscious; and third, we

come to see our values as being connected to the universe in a tangible way.

Why does this third

insight matter so much? Because it refutes everything else atheists claim to

know. Under the moral realist model, our values are the beliefs that maximize

the probability of our survival. The moral realist model guides us to formulate

and live by values that work. Trying to be good matters.

Thus, moral realism

is not trivial. It is vital. How you act is going to contribute in real ways to the survival odds of you, your children, and your species. The way to act if you want to improve the odds of all of those things surviving is to live by courage, wisdom, freedom, and love.

The inescapable implication of seeing moral values as being arbitrary and trivial is seeing one's own existence as trivial. And for real people living real lives, that just is not how life feels.

The inescapable implication of seeing moral values as being arbitrary and trivial is seeing one's own existence as trivial. And for real people living real lives, that just is not how life feels.

Belief in the

realness of values is not trivial just as belief in the consistency

of the universe is not trivial. Both beliefs have an effect – via the kinds

of thinking and behavior they cause in us – on the odds of our survival. In the

long haul, Science is good for us. So is Moral Realism. People who carry these

programs in their heads outwork, outfight, outbreed, and outlast the

competition. Moral Realism's worldview, we can now see, does describe reality.

Our reality.

Thus, belief in the

realness of our values enables us to see that the presence that fills the

universe doesn’t just stay consistent and even have a kind of awareness. It

also favors those living entities that follow the ways we call “good.”

It cares.

In my own

intellectual, moral, and spiritual journey, I went a long time before I could

admit even to myself that by this point I was gradually coming to believe in a

kind of deity. God.

Fourteen billion

light years across the known parts of the universe. Googuls of particles. 1079 instances

of electrons alone, never mind quarks or strings. And all of these are

integrated parts of one thing -- consistent, aware, and compassionate,

all over, all at once, all the time.

And these claims

describe only the files of evidence that we know of. What might exist before or

after, in smaller or larger forms, or even other dimensions that some

physicists have postulated? We can’t even guess.

And it cares.

Every idea about matter

or space that I can describe with numbers is a naïve children’s story compared

with what is meant by the word infinite. Every idea I can talk

about in terms that name bits of what we call time must be set

aside when I use the word eternal. For many of us in the West,

formulas and graphs, for far too long, have obscured the big ideas, even though

most scientists freely admit there is so much that they don’t know.

Isaac Newton said: “I

seem to have been only a boy playing on the seashore, diverting myself in now

and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst

the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”9

And it cares.

With beliefs in the coherence shown to us by Science, in the Universal Awareness we see in quantum theory, and in Moral Realism firmly in place, Wonder

arrives.

This way of living

resolutely by moral guidelines whose consequences may take

generations to arrive is exactly what is meant by the word faith.

Belief in things not seen.

This theistic view,

when it’s widely accepted in society, also is utterly consistent with Science.

A general adherence in society to the moral realist way of thinking is what

makes communities of scientists doing Science possible.

Consciously and individually, every scientist should value wisdom and freedom, for reasons that are uplifting, but even more because they are rational. Or rather -- to be more exact -- rational and uplifting, fully understood, turn out to be the same thing. As Keats told us, beauty is truth, truth beauty.

Consciously and individually, every scientist should value wisdom and freedom, for reasons that are uplifting, but even more because they are rational. Or rather -- to be more exact -- rational and uplifting, fully understood, turn out to be the same thing. As Keats told us, beauty is truth, truth beauty.

Scientists know that

figuring out how the events in reality work is personally gratifying. But more

importantly, each scientist should see that this work is done most effectively

in a free, interacting community of scientists functioning as one sub-culture

in a larger social ecosystem where freedom and love reign.

Many of us in the

West have become deeply attached to our belief in Science. We feel that

attachment because we’ve been programmed to feel it. Tribally, we believe that

our modern wise men – our scientists – doing research and sharing their findings are

vital to the survival of the human race.

Back on the personal tack then, I concluded years ago that of all the

subcultures within democracy that we might point to, none is more dependent on

the moral realist values than is Science.

Scientists have to

have courage. Courage to think in unorthodox ways, to outlast derision,

neglect, and even ridicule, and to work, sometimes for decades, with levels of

determination and dedication that people in most walks of life would find hard

to believe. (Yes, decades.)

Scientists need the

sincerest form of wisdom. Wisdom that counsels them to listen to analysis and

criticism from their peers without allowing egos to cloud their judgement, and to

sift through what is said for insights that may be used to refine their methods

and try again.

Scientists need

freedom. Freedom to pursue Truth where she leads, no matter whether the truths

discovered are unpopular or threatening to the status quo.

Finally, scientists

must practice love. Yes, love. Love that causes them to treat every other human

being as an individual whose unique experience and thought may prove valuable to their

own. Science is only possible in a community.

Scientists recognize

that no one human mind can hold more than a tiny fraction of all there is to

know. They must respectfully share and peer-review ideas and research in order

to advance, individually and collectively.

Scientists do their

best work in a community of thinkers who value and respect one another, who

love one another, so much as a matter of course that they cease to notice

another person’s race, religion, sexual orientation, or gender. Under the

cultural model of human evolution, one can even argue that creating a social environment

in which Science can flourish is the goal toward which democracy has always

been striving.

But these are just

pleasant digressions. The main implication of the moral realist way of thinking is even

more personal and profound, so let’s return to it now.

The universe is

coherent, aware, and compassionate. Belief in each of these

qualities of reality is a separate, free choice in each case. Modern atheists

insist that far more evidence and weight of argument exist for the first than

for the second or third of these three traits. My contention is that this is no

longer so. Once we see how our values connect to reality, the theistic choice

becomes a reasonable one and an existential one. It defines who we are.

Therefore, belief in

God emerges out of an epistemological choice, the same kind of choice we make

when we choose to believe that the laws of the universe are consistent.

Choosing to believe, first, in the laws of Science, second, in the self-aware

universe implied by quantum theory, and third, in the realness of the moral

values that enable democratic living (and Science) entails a further belief in

a steadfast, aware, and compassionate universal consciousness. God.

Belief in God follows

logically from my choosing a specific way of viewing this universe and my

integral role in it: the scientific way.

The problem for

stubborn atheists who refuse to make this choice is that they, like every other

human being, have to choose to believe in something.

Each of us must have

a set of foundational beliefs in place in order to function effectively enough

to move through the day and stay sane. The Bayesian model rules all that I

claim to know. I have to gamble on some set of axioms in order to move through

life. The only real question is: “What shall I gamble on?”

Reason points to the

theistic gamble as being not the only choice, but the wisest choice of the

epistemological choices before us. I’m going to gamble that God is real. As far

as I can see, I have to gamble on some worldview, and theism is the best

gamble. It makes all my ideas come together into one coherent system that I can follow readily as I make choices and implement them in all aspects of life.

Theism - belief in a single, conscious, compassionate entity that is present in all the universe all the time - is simply more efficient than any competing way of thinking ever could be. It makes effective, prudent, timely action possible.

Theism - belief in a single, conscious, compassionate entity that is present in all the universe all the time - is simply more efficient than any competing way of thinking ever could be. It makes effective, prudent, timely action possible.

The best gamble in

this gambling life is theism. Reaching that conclusion comes from looking at

the evidence. Following this realization up with the building of a personal

relationship with God, one that makes sense to you as it also makes you a good

friend – that, dear reader, is up to you. Do it in a way that is personal. That

is the only way in which it can be done truly, if it is to be done at all.

To close in an unashamedly personal way, then.

Once one truly believes in the theistic conclusion, does life remain hard? Always. Adversity is an inherent feature of life in this universe. But we evolved to work. If life got easy and idle, we would deeply long for challenge. And please note that life has been safe for some spoiled children of the rich. For a while. But these people who don't know challenge, know ennui. Meaninglessness. Look at the evidence.

Will life remain scary, uncertain, if one sees that theism really does make sense? Of course. But seeing the whole, giant picture also affirms for us once and for all that the flip side of living in a stochastic universe is freedom. Uncertainty/anxiety is the price of freedom. The joy and the pain of conscious existence. The best response to such a realization is more than just work. It is imagination. Creativity. And best of all, we realize that permeating this whole way of thinking is the knowledge that love is real. It will triumph -- if we practice it well. Because that's how reality is built.

To close in an unashamedly personal way, then.

Once one truly believes in the theistic conclusion, does life remain hard? Always. Adversity is an inherent feature of life in this universe. But we evolved to work. If life got easy and idle, we would deeply long for challenge. And please note that life has been safe for some spoiled children of the rich. For a while. But these people who don't know challenge, know ennui. Meaninglessness. Look at the evidence.

Will life remain scary, uncertain, if one sees that theism really does make sense? Of course. But seeing the whole, giant picture also affirms for us once and for all that the flip side of living in a stochastic universe is freedom. Uncertainty/anxiety is the price of freedom. The joy and the pain of conscious existence. The best response to such a realization is more than just work. It is imagination. Creativity. And best of all, we realize that permeating this whole way of thinking is the knowledge that love is real. It will triumph -- if we practice it well. Because that's how reality is built.

Notes

1. Nicholas

Maxwell, Is Science Neurotic? (London, UK: Imperial College

Press, 2004).

2. “History of

Science in Early Cultures,” Wikipedia,

the Free Encyclopedia.

Accessed

May 2, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_in_early_cultures.

3. Mary Magoulick,

“What Is Myth?” Folklore Connections, Georgia College & State

University.

4. “Pawnee

Mythology,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May

2, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pawnee_mythology.

5. “Quantum

Entanglement,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May

2, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_entanglement.

6. Jonathan

Allday, Quantum Reality: Theory and Philosophy (Boca Raton,

FL: CRC Press, 2009), p. 376.

7. “Quantum Flapdoodle,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May 2, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_mysticism#.22Quantum_flapdoodle.22.

8. “Occam’s

Razor,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed May

4, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.