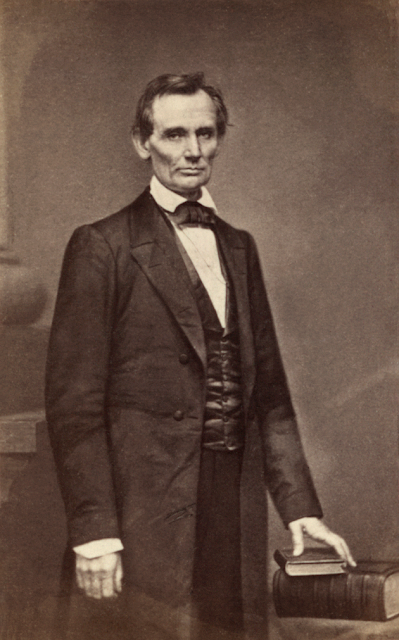

Abraham Lincoln (1860) (credit: Mathew Brady, via Wikipedia)

Thinking of

Lincoln Today

I have spent much of my

life trying to work out a code of ethics grounded in observable, objective,

material, empirical reality. And I have, at least in my own judgement, done so.

That is what the book that I have put up on this site four times, in successive

iterations, has explained. A universal moral code.

But no matter what code

of ethics we live by, it gets tested, and we get tested, most acutely in the

material world when we interact with other human beings.

So how does moral realism

do in real life?

On this subject of

interacting morally with others, let’s remind ourselves of some basics. We live

in a quantum universe, not a random one, but not a deterministic one either.

Events follow each other in sequences that are not inescapably linked by laws

of Newtonian physics, but rather succeed each other in ways that are shaped by

probabilities. And living things can intervene in these sequences and alter the

odds of subsequent events occurring. Humans especially are very good at raising

the odds of those events that they would like to see happen and lowering the

odds of those they want to avoid. We learn from mistakes and store up what we

learn in our cultures, then pass the learning on to our children. This is how

moral realism sees us functioning in the real world.

All of this scenario

depends on human judgement, which is always subject to error in every one of

us. I can’t foresee every pandemic, but I can say with a high degree of

confidence that new viruses and bacteria are going to come along to attack us

every so often. Why am I confident that this will be so? Because it always has

been so, as far back as we can see into our past. And we understand fairly well

how viruses mutate and evolve. And we understand fairly well how our immune

systems gradually build resistance to any new virus that comes along. So we

make predictions and take precautions, and respond (via vaccines) and we

survive in much greater numbers than we would have if we hadn’t taken those measures.

Our cultures in today’s world have taught us all of this.

Similar things can be

said about how we try, with much success actually, to forecast what the weather

and the climate are going to do in both the near and distant futures and when

our food production might get hit by a drought or a new insect pest. The point

is that humans in a quantum universe have free will. We can’t make everything

we would like to see happen really happen, but we can avoid many hazards and

improve the odds of good harvests, and so on.

Thus, in this quantum

universe, it is also guaranteed that we all will make at least some decisions

and take at least some actions that we will later come to regret. To wish we

could take back. Those aren’t “sad facts of life in the real world”. They are

more hopefully seen as evidence of just how free we really are.

Why? Because sometimes

when we make a mistake, especially in how we treat other human beings, we can

make amends later. Make the wrong, right. And with some mistakes, our wisest

course is to let them go. And I’ll stress again: we all make mistakes. We use

our best judgement, decide, and act. But no measures we take for the future

succeed all the time. But we have to act. Reality demands that we do. So we do

the best we can with what we know at the time. And under a moral realist code –

always – we aim to restore and maintain balance, in ourselves, our families,

our communities, and our world, because we see our societies as evolving

ecosystems. Balance is the “good” in an ecosystem view.

When we recognize these

truths, we can forgive those of our brothers and sisters who may have done

things that hurt us. Let the past go. Start again. It is loving, and even more

in the long haul, it is wise to do so. We, too, have made mistakes.

Why is this matter on my

mind today? In truth, I have been thinking about it for weeks, but today

contained a special bit of news from the U.S. that I have been mulling over

since early morning. It could serve as a paradigm for us all.

CNN, the cable news

network, showed some footage this morning of a man in an Arkansas hospital who

refused to get vaccinated against Covid 19, but who has now contracted it. He

is very sick. He may die.

He is repentant and

contrite and very afraid that he might have passed the virus on to some of his

family members. In short, he has realized he made a mistake.

All I could think,

immediately and viscerally, was: “Oh, no, buddy don’t die. I may have at times

in the past few months felt a lot of hostility toward people like you, but I

never once wished for them, or you, to die.”

What’s interesting about

this anecdote is that it reveals sharply how democracy enables, even enhances,

our capacity to forgive each other.

Yes, there is a lot of

anger in some parts of the U.S., and not just over Covid, against what people in

those regions see as the corrupt and cynical masses on the coasts who profess

to believe in no moral values and who show only callous indifference, even

mockery, to those with less education.

And their feelings now,

after decades of being mocked, are something like: “We’re not listening to you

anymore. Period.” That’s the stance of many in the South and in the Rust Belt.

This situation must

change on all sides. And democracy shows us a way out.

Americans have learned to

forgive each other before. The Civil War especially saw Americans do terrible

things to each other. But after the war, President Lincoln was still able to

say, in his second inaugural address:

With

malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God

gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to

bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and

for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just

and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

After all he had endured for his nation – the

hundreds of thousands of casualties that he felt personally, his young son

dying of typhoid fever in 1862 and his wife succumbing to a crushing clinical

depression for months afterward – Lincoln could still speak of malice toward

none. He had no smart-aleck remarks for the citizens of the defeated South. No mocking

innuendos.

America must get that back. That policy of

reconciliation didn’t work perfectly, partly because Lincoln died not long

after that speech and partly because some on both sides still carried a lot of

anger long after the Civil War. But the nation succeeded a lot more than it

would have if Lincoln and large sectors of the North had inflicted as large a

penalty on the South as they could have done. The U.S. restored a large measure

of balance and went on.

Liberals: however much you may rage inwardly

against the kinds of tactics that some of Donald Trump’s minions and supporters

have employed, only those people who have broken the law, as in the Jan. 6

insurrection, should be dealt with. One at a time. In the courts. And liberals

would also be wise to remind themselves constantly that those few hundred were

not representative of all 70+ millions who voted for the man liberals so love

to despise.

Democracy – the real-world form that moral

realism takes – provides paths by which feelings of rage and fear may be worked

out rationally. Then, in the plan of democracy, the hottest heads on all sides

cool down. Decency and sense, measured responses to real crimes, can prevail.

Keep thinking of Lincoln. Five million white

citizens in the 1860s South did not shoot him in Ford’s theater. Just one man

did. Lincoln died still holding up a model of restraint and forgiveness. And not

just to Americans. He belongs to the ages.

And America? America is alive, well, and recovering her

strength once again.

Abraham Lincoln (1863) (credit: Alexander Gardner, via Wikipedia)

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.