Alex Jones (credit: Jaredholt, via Wikimedia Commons)

So

We Gamble

We

gamble. On every idea we use to think, every scientific law, every concept we

believe in, in fact, every word we say. Why do I say that we gamble? Because that

is the exactly correct way to put what we do when we think, and then talk, about all kinds of subjects, even mundane, everyday topics, our routines, our roles

in acting out familiar situations, and so on.

Our words don’t somehow attach to any things in the real world by perfectly logical, unchallengeable connections. But we have to have the concepts that the words try to name, or we can’t think at all. So we do the best we can to define our terms clearly, and then we talk and reason, again, as best we can.

For example, what makes a “cell”

in the living world can get tricky to pin down. Most of the time, by far, we

can view all living things as being made of units that we call “cells”. A cell

has a number of properties that we say are properties that qualify it as a

cell. It has levels of organization, it uses energy, grows, reproduces, and

adapts to changes in its environment. But then we must ask: is a virus a cell?

Biologists

say “yes and no”. A virus has some cell properties, but not all. So, do we

get tongue-tied when we talk about viruses? No. We simply amend our discourse.

We make it clear that we are going to talk about viruses when that is what we

intend to do, and we agree for the time being not to talk about whether they

are cells or not. We talk our way around the problem, and we then can get done

things that need to get done. We can even cooperate to do research aiming to

find a cure for a new virus.

Electron microscope image of covid virus (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Similar

troubles afflict our talk about atoms. We have some idea of what an atom looks

like. We can see images of atoms by focusing an electron microscope on them.

But then what are atoms made of? Can we see those particles? We call them

“quarks”, and we have some ideas about them, but no, we can’t see them or even

see images of them via electron microscopes. Quarks are just too tiny. We can

talk about experimental evidence that we get when we bombard quarks with other

particles, but we can’t say we know what quarks look like. At least not with

the technologies that we have mastered so far.

And

our concepts get shakier. Once chemists thought “phlogiston” was a real

substance that was in everything that could burn. Then, Antoine Lavoisier did

experiments that proved phlogiston simply did not exist. Not that phlogiston

was too tiny for us to detect, but that it didn’t exist at all. It was only

imaginary.

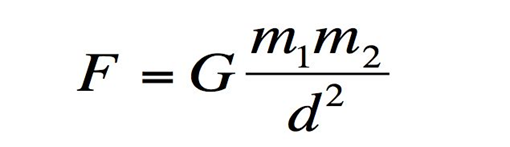

The

law of gravity says any two bodies in space are pulled together by a force that

is proportional to the product of their masses divided by the square of the

distance between them. In short, any two bodies pull on each other, and the

pull gets greater the heavier they are and the closer together they are.

However, we should also note that the distance between them, as it gets

greater, lessens the pull much faster than reducing what they weigh does. In

math terms, this whole relation is expressed as:

The

force, F, pulling any two bodies together is equal to the product of their two

masses, m1 and m2, divided by the square of the distance

between them, d2, times a gravitational constant that we can figure

out by doing experiments with objects in the material world, and that we choose

to call “G”. A pretty simple equation, one that we believed for a long time was

always true everywhere. Using this law, scientists hundreds of years ago were

able to figure out the orbits of the planets, and how long things here on earth

would take to fall to the ground when they were dropped from a tower, and many

other calculations. It was an infallible equation. We thought.

Unfortunately,

even physicists, the scientists most dedicated to being precise, found out in

the late 1800s that this formula doesn’t always work. When we start to talk

about very heavy things like our sun, or when the two bodies are moving very

fast, this formula that describes how gravity supposedly works gives us inaccurate

predictions. And then Relativity Theory was proved and it profoundly modified

our ideas about Gravitational Theory.

In

other words, even the most rigorous statements of the laws of nature that

scientists have found … don’t always work. How much shakier must ideas like

“ethnicity”, “ego”, “courage”, “love”, or “justice” be?

I

bring these matters up today because of Alex Jones. Stay with me. These two

topics do connect.

What

do the laws of science have to do with Alex Jones? Well, his followers can say

that there are no one hundred percent reliable rules that anyone can follow in

this world so when they give their trust to Jones, they aren’t being any less

reasonable than followers of CNN or the Center for Disease Control. In the end,

all of our talk is just opinions.

At

first glance, the Jonesies seem right. All of our definitions for all the terms

that all of us use are tenuous. But the Jonesies are wrong for several reasons.

In

the first place, science and its predictions are backed up by careful review

and research done by many scientists in many parts of the world. In fact, in

every controversial case, some of these scientists really don’t like or trust

each other so they are motivated to try to disprove each other’s statements. In

short, the statements of science are peer-reviewed. Advice given by scientists

is not based on what a few of them, or even many of them, would like to find in

their research, but instead on observable facts that have been tested multiple

times, using tests that can be repeated – with the same results – again and

again.

Then,

in the second place, the scientists do not tell the rest of us, and especially don’t

tell the politicians making decisions about how to spend taxpayers’ money, any

statements that they claim are perfectly true. They just tell us what they

think is very likely to be true given the carefully sifted advice of thousands

of scientists.

Thirdly,

scientific theories do get changed as decades go by, but the changes are made

by better science. Only after a new theory has been thoroughly examined and its

predictions tested many times is it accepted by scientists as …truth? No. It

then gets accepted as a better way of describing reality, but never as the last

word, the final way of describing any aspect of the real world.

In

addition, scientists are specialists: intelligent people who have given their

lives to the study of a particular field. Only those specialized in the area

that citizens and their politicians are dealing with give advice on any

specific topic. Climate scientists give advice on global warming, one of the

things they study intensively. They do not give us advice on epidemics like

Covid. Epidemiologists do that. And epidemiologists don’t give out advice on

the economy or on sports medicine or even on how to grow vegetables in a

greenhouse during the winter. Tony Fauci did not comment on the images from the

Webb space telescope.

Furthermore,

psychologists give us a general caution about all our beliefs: be suspect of

every story and every bit of advice that tells you what you wanted to believe

before you began investigating the topic. Any topic. Psychologists have volumes

of research on how people form beliefs and reach conclusions based on those

beliefs. They are (fairly) certain that we all lean toward believing what we

want to believe, what will require little or no adjusting on our part.

Looking

past one’s own biases and reviewing a lot of research from multiple, qualified,

long-established sources – ones with good records going back decades – takes

work. Years of practice. And sometimes, even scientists get fooled. For a

while. The case of Andrew Wakefield is an instructive one. He was wrong;

vaccines don’t cause autism. But it took many scientists going back over the

research to see why that was so.

Now,

if science is that cautious about its terms and concepts and theories, how much

more vulnerable to faulty reasoning are the rest of us as we think about and

discuss more common matters? Can any of us precisely define “justice”,

“rights”, “crime”, “evidence”, or “opinion” – to name only a few key concepts –

as precisely as biologists define “cell”? No wonder we blunder. In everyday

discussions, we often, literally can’t agree on what we’re talking about.

And so we come to Alex Jones. I

don’t trust him, but that’s not because I can prove his theories are

impossible. No, I don’t trust him because his theories about events in our

world are based on groundless speculation. Not evidence.

Evidence,

for science-minded folk like me does not qualify as evidence until it can be

put in front of any people out in the public and it is incontrovertible. Did

that mixture of chemicals in the beaker turn blue or didn’t it? Did the eclipse

of the sun occur when the astronomers said it would? Do people who take this drug

really get well again? Does this additive in your gas tank really make your car

go ten percent further on a tank of gas? Did the bacteria become resistant to

the new antibiotic as quickly as the bacteriologist said they would?

Jones

and his ilk care nothing for eclipses of the sun, but there are other, more

Jones-relevant subjects. Are there any child-killers hiding in a DC area pizza

joint? Says who? What is their evidence? If the Sandy Hook tragedy was staged

by manipulative politicians who hate guns, then what was in those little

coffins? Why can people there still tell stories of their lives that

corroborate each other?

Or

was it all a big act played out by hundreds of actors who never let a clue about

the hoax slip to anyone ever? What are the odds?

The

chances that there is a world-wide conspiracy aiming to replace the white race

with people of color are pretty close to zero. Just like the odds that Covid

was the result of a government plot or the odds that the parents who say their

kids were killed in Sandy Hook are professional actors who staged a school

shooting, one that – Jones says – never actually happened.

The

odds that Jones is telling us some huge, government-guarded secrets are as

close to zero as they can get in this world. In fact, after the number of lies

he has told, I believe he’s only making up stuff to gain listeners and readers

who will buy his quack cures for multiple ailments and send him lots of money.

There

really was, and is, a Covid pandemic. The Sandy Hook school shooting really

happened. Airplanes flown by terrorists did fly into the Twin Towers in 2001. There

is no New World Order trying to eliminate the white race. I’m willing to gamble

everything I have on the truthfulness of these statements.

The

final point in this argument, then, is the realization that any of these

events, if it was a hoax, would have needed thousands of people to plan and participate

in it. In every case of Jones’ wild claims, we can ask: what are the

odds of that many people perfectly guarding a secret that big? The odds of

there being not one peep from any of those thousands of participants?!

No, Alex. After long consideration of all the facts, and after weighing the odds on several of your theories, I've decided that it's far more likely that you are the hoax. You're a quack manipulating people in order to sell cures that cure nothing.

But really, you know, your quack cures are small matters compared to some others you've meddled in. Most especially, Sandy Hook. And for the way you hurt the parents of the Sandy Hook victims, some might think a just punishment would be for you to lose one of your children to gun violence. But no, my bet is that even those parents, who ache every day for their lost little ones, would never wish that much suffering onto any other human being, not even you.

President Barack Obama speaking after Sandy Hook shootings, 2012

(credit: Lawrence Jackson, via Wikimedia Commons)

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.