Chapter 17. (continued)

My

model of cultural evolution also showed me why some superstitious beliefs hang

on for generations before they are dispelled. But in the end, as old thinkers

are replaced by more enlightened ones, the method of human learning, whether it

is individual or tribal, is an inductive one. We get ideas about the material

world and we test them. We sometimes test world views or moral systems over

generations, and what we learn is absorbed by the tribe over generations rather

than cognized by any one individual.

But our knowledge keeps growing, as it

must if we are to survive. We are the only concept-driven species that we have encountered

so far. The knowledge-accumulating, social way of surviving is the human way.

Our genetically-acquired assets (speed, strength, etc.) are trivial by

comparison. We live by learning or we die.

As

we think about how science and its methods work, we realize, as Nicholas

Maxwell has stressed many times, that it contains one more implicit assumption.

This second assumption is that human minds can figure out the laws of this

difficult and confusing place; that is, that we’re not kidding ourselves about

how smart we are. All the evidence of the history of Science, and of humanity

more generally, suggests that we can figure those laws out.

Therefore, I choose

to gamble again, this time on the power of human minds, sometimes alone and sometimes

in cooperation with other minds, to see through the layers of irrelevant,

trivial events and to spot the patterns that underlie their larger movements.

Then we can test and revise and gradually arrive at models and natural law

statements that really do explain the world, and so we gradually come to master

the knowledge that empowers us to design—and engage in—focused, strategic

actions that get survival-favoring results.

Again,

the majority of the citizens of the West see this choice-gamble as the only

rational one to take. The alternative to believing in the power of human minds,

individually or in cooperating groups, to figure out the laws underlying

reality is to abandon reason in favor of beliefs founded on something other

than observable, replicable, material facts.

Once again, we have the evidence

of centuries of human history to look back on. All the evidence we have about

what life was like for the superstitious, cowed tribes of the past suggests

that their lives were—as Hobbes puts it—nasty, brutish, and short. People who

were willing to think, analyze, experiment, and learn made this society that we

enjoy today; even the majority of Luddite cynics who claim to despise modernity

won’t go two days without a shower.

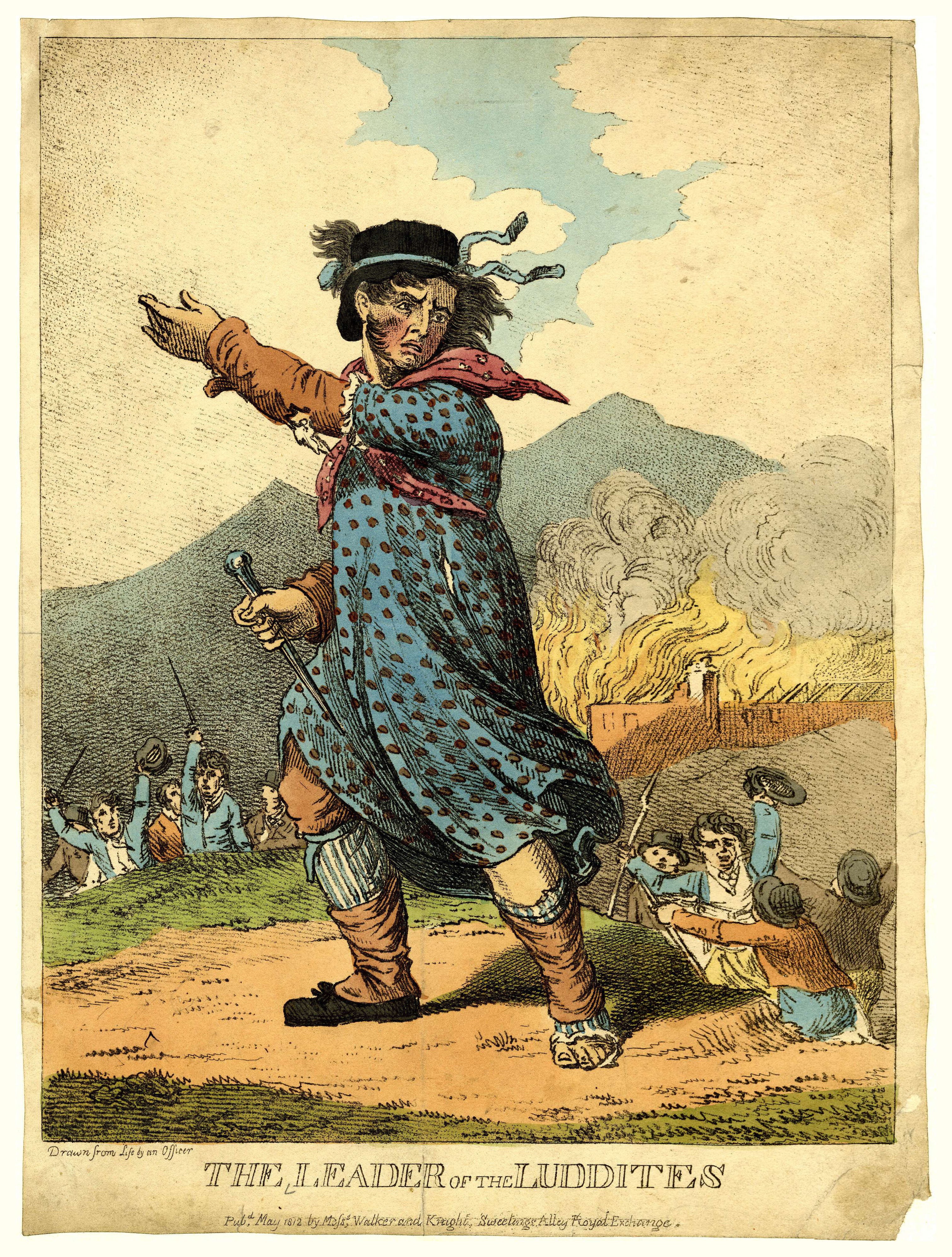

1812 engraving of (purportedly) Ned Ludd

My

first point or conscious realization on the road to the theistic view, then, is

that these beliefs in the consistency of the laws of the universe and in the

power of the human mind to figure them out, when added together, amount to a

kind of faith. To atheists and skeptics, this belief system can’t properly be

called a “faith” at all. It certainly doesn’t lead them to a belief in God. It

simply enables atheists and theists alike to keep doing science and to share

ideas about science with anyone else who is interested. It does not entail more

than that, the atheists say.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.