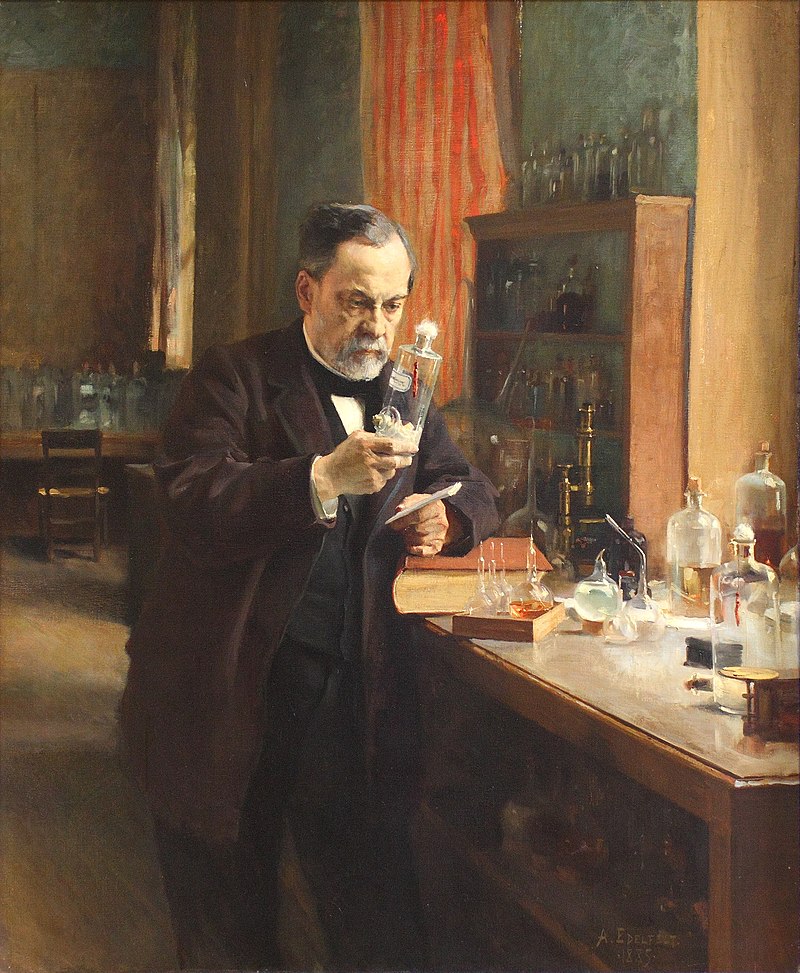

Pasteur in his laboratory (artist: Eldelfeldt) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

An

indifferent reaction to a new theory’s handling of confusing old evidence is

simply not what happens in real life. When physicists around the world realized

that the Theory of Relativity could be used to explain the shift in the orbit

of Mercury, their confidence that the theory was correct shot up. Their

reaction was anything but indifferent. Most humans are exhilarated when a new

theory they are just beginning to understand gives them solutions to unsolved

old problems.

Hence,

the critics say, Bayesianism is obviously not adequate as a way of

describing human thinking. It can’t account for some of the ways of thinking

that we’re certain we use. We do indeed test new theories against old, puzzling

evidence all the time, and we do feel much more impressed with a new theory if

it can account for that same evidence when all the old theories can’t.

The

response in defense of Bayesianism is complex, but not that complex. What the

critics seem not to grasp is the spirit of Bayesianism. In the deeply

Bayesian way of seeing reality and our relationship to it, everything in the

human mind is morphing and floating. The Bayesian picture of the mind sees us

as testing, reassessing, and restructuring all our mental models all the time.

In the

formula above, the term for my degree of confidence in the evidence, when I

take only my background assumptions as true—namely, the term Pr(E/B)—is never 100 percent. Not even for very familiar old

evidence. Nor is the term for my degree of confidence in the evidence if I do

include the hypothesis in my set of mental assumptions—i.e. the term Pr(E/H&B)—ever

equal to 100 percent. I am never perfectly certain of anything, not of my

background assumptions and not even any of the evidence I have seen repeatedly

with my own eyes.

To

closely consider this situation in which a hypothesis is used to try to explain

old evidence, we need to examine the kinds of things that occur in the mind of

a researcher in both the situation in which the new hypothesis does fit the old

evidence and the one in which it doesn’t.

When the

hypothesis does successfully explain some old evidence, what the researcher is

affirming is that, in the term Pr(E/H&B), the evidence fits the hypothesis,

the hypothesis fits the evidence, and the background assumptions can be

integrated with the hypothesis in a comprehensive way. She is delighted to see

that, if she commits to this hypothesis and the theory underlying it, that will

mean she can feel reassured that the old evidence did happen in the way in which

she and her colleagues observed it. In short, she and her colleagues can feel

reassured that they did their work well.

Sloppy

observation is a haunting fear for all scientists. It's nice to learn that you

didn't mess up.

All these

logical and psychological factors raise her confidence that this new hypothesis

and the theory behind it must be right.

This

insight into the workings of Bayesian confirmation theory becomes even clearer

when we consider what the researcher does when she finds that a hypothesis does

not successfully account for the old evidence. Rarely in scientific research

does a researcher in this situation simply drop the new hypothesis. Instead,

she examines the hypothesis, the old evidence, and her background assumptions

to see whether any or all of them may be adjusted, using new concepts or new

calculations involving newly proposed variables or closer observations of the

old evidence, so that all the elements in the Bayesian equation may be brought

into harmony again.

When the

old evidence is examined in light of the new hypothesis, if the hypothesis does

successfully explain that old evidence, the scientist’s confidence in the

hypothesis and her

confidence in that old evidence both go up. Even if her prior confidence in

that old evidence was really high, she can now feel more confident that she and

her colleagues—even ones in the distant past—did observe that old evidence

correctly and did record their observations accurately.

The value

of this successful application of the new hypothesis to the old evidence may be

small. Perhaps it raises the E value in the term Pr(E/H&B) only a fraction of 1 percent. But that

is still a positive increase in the value of the whole term and therefore a

kind of proof of the explicative value rather than the predictive value of the

hypothesis being considered.

Meanwhile,

the scientist’s degree of confidence in this new hypothesis—namely, the value

of the term Pr(H/E&B)— also goes up another notch as a result of the

increase in her confidence in the evidence. A scientist, like all of us, finds

reassurance in the feeling of mental harmony when more of her perceptions,

memories, and concepts about the world can be brought into cognitive consonance with each other.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.