The Bayesian way of thinking about our own thinking

requires us to be willing to float all our concepts, even our most deeply held

ones. Some are more central, and we stand on them more often and with more

confidence. A few we may believe almost, but not quite, absolutely. But in the

end, none of our concepts is irreplaceable.

For humans, the mind is our means of surviving. It

will adapt to almost anything.

We gamble heavily on the concepts we routinely use

to organize our sense data and memories of sense data. I use my concepts to

organize the memories already stored in my brain and the new sense data that

are flooding into my brain all the time. I keep trying to acquire more concepts

– including concepts for organizing other concepts – that will enable me to

utilize my memories more efficiently to make faster and better decisions and to

act increasingly effectively. In this constant, restless, searching mental life

of mine, I never trust anything absolutely. If I did, a simple magic show would

mesmerize and paralyze me. Or reduce me to catatonia.

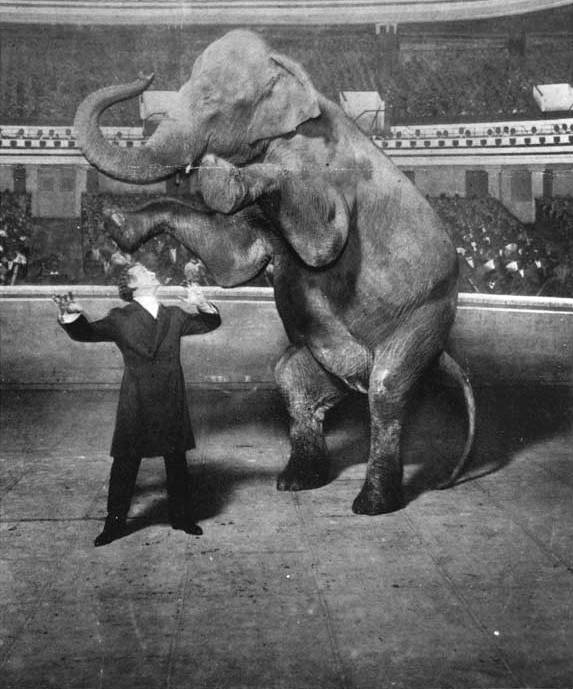

When I see elephants disappear, women get sawn in

half, and men defy gravity, and all come through their ordeals in fine shape,

some of my most basic and trusted concepts are obviously being violated. But I

choose to stand by my concepts in almost every such case, not because I am

certain they are perfect but because they have been tested and found effective

over so many trials and for so long that I’m willing to keep gambling on them.

I don’t know for certain that they are sure bets; they just seem like the most

promising options available to me.

Harry Houdini with his “disappearing”

elephant, Jennie

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Life is constantly making demands on me to move and

keep moving. I have to gamble on some things; I go with my best horses, my

oldest, most successful and trusted concepts. And sometimes, I change my mind.

This mental flexibility on my part is just life. Bayesianism

is telling us what Thomas Kuhn said in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. We are constantly

adjusting all our concepts to try to make our ways of dealing with reality more

effective.

And when a researcher begins to grasp a new

hypothesis and the model or theory it is based on, the resulting experience is

like a philosophical or religious “awakening”—profound and even life-altering.

Everything changes when we accept a new model or theory—because we change. In

order to “get it,” we have to change. We have to eliminate some of the old

beliefs from our familiar background set.

And what of the shifting nature of our view of

reality and the gambling spirit that is implicit in the Bayesian model? The

general tone of all our experiences tells us that this overall view of our

world and ourselves, though it may seem scary or perhaps, for more confident

individuals, challenging—is just life.

We have now arrived at a point where we can feel

confident that Bayesianism gives us a good base on which to build further

reasoning. Solid enough to use and so to get on with all the

other thinking that has to be done. It can answer its critics—both those who attack it with real-world

counterexamples and those who attack it with pure logic.

So here is a good place to pause to summarize our

case so far in a new chapter devoted just to that summing up.

Notes

1. Thomas Kuhn, The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: The University of Chicago

Press, 3rd ed., 1996).

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.