Chapter 19 Moral Realism Connects to Theism

At this stage of my

argument, then, a comprehensive summing up is needed. A perspective as large as

we can broaden our minds to take in. In order to finish the argument and bring

all the threads together, I must first go backward and carefully review some of

the assumptions that are implicit in this argument, as they are in any argument

that is based on Science.

So. What are we

committing to if we agree with the points presented so far and with some others

that the entire argument has been implicitly assuming? Three ideas are

essential.

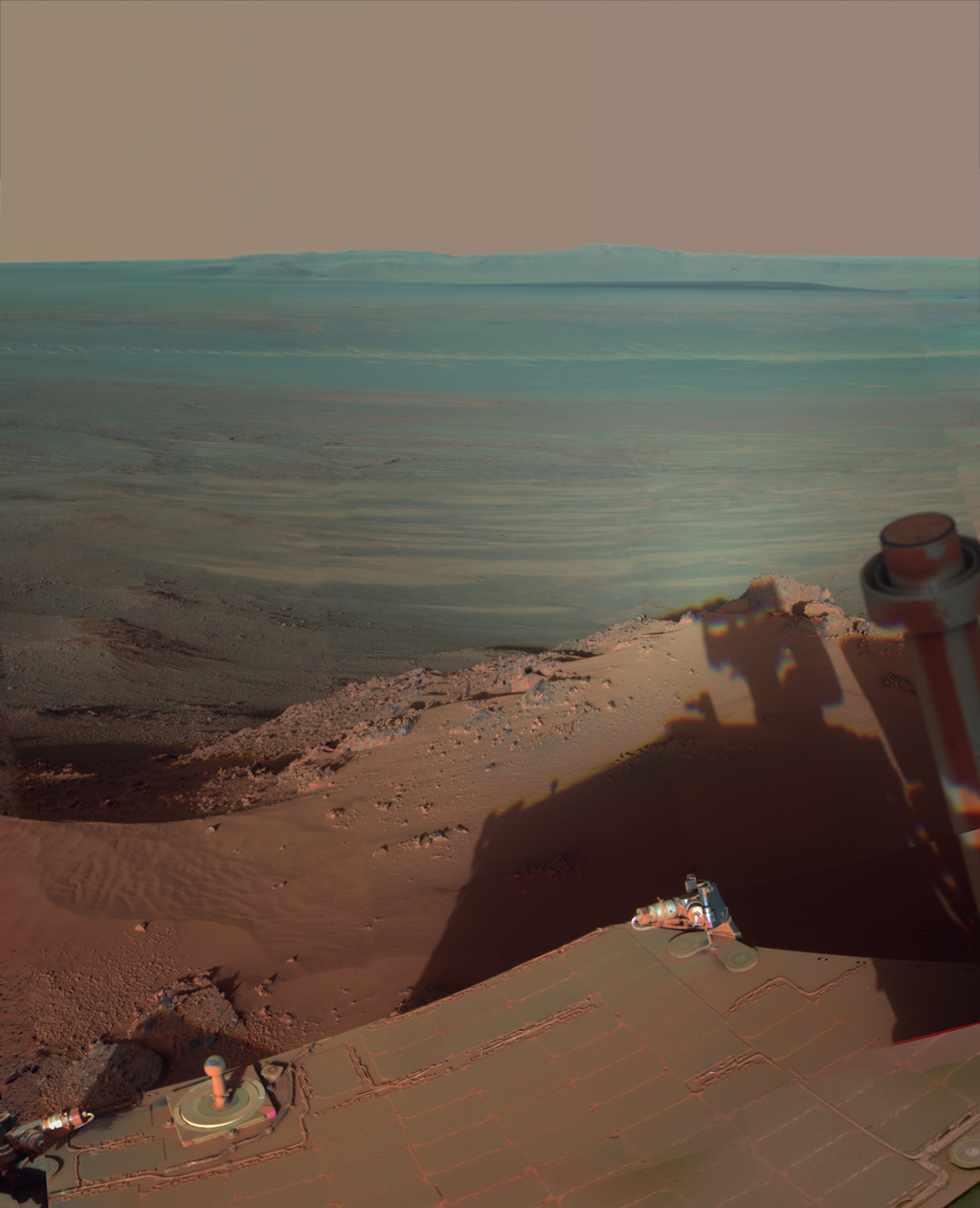

Afternoon on Mars (photo by the

NASA probe, Spirit Rover)

(credit: Wikimedia

Commons)

In the first place, a

basic assumption – for many modern thinkers, an implicit assumption they are

not conscious of and do not examine – is that the universe is a single,

integrated system. Every one of its parts connects to all of its other parts.

The universe runs by one set of laws, each law consistent with all the others.

We don’t fully understand the system of natural laws yet. For example, we don’t

yet understand how sub-atomic forces and electro-magnetism relate to gravity.

But in doing Science, we implicitly assume that the laws of Science apply on Gliese

581g, Mars, etc. just as precisely as those laws apply here on Earth. (Dennis

Overbye sums up the debate in a 2007 New York Times article.1)

To some readers this

assumption may seem so self-evident that stating it feels silly. But such a

reaction is too hasty. If we are scientific thinkers, this basic assumption of

Science informs all else that we contemplate and do.

To be even plainer,

let’s compare this idea that our universe is all one system with the idea’s

alternative. In short, let’s ask, “As opposed to what?”

Artist’s conception of the Gliese 581 system

(credit: ESO/L. Calçada, via Wikimedia Commons)

The alternative view

of our universe sees it as being made up of areas or eras in which different

sets of rules apply or once did apply. This was the view of our forebears. They

saw the universe as being run by many varied and mutually hostile gods, each

with his or her own realm.

For example, for the

ancient Greeks, Poseidon ruled the sea; he could make storms at will and bring

them down on any mariners he disliked. Hades ruled the underworld, Zeus, the

skies. Hades seized Persephone and took her to his realm; even Zeus could only

negotiate to get her back to her mother for half the year. From this quarrel

came the seasons. Two bellicose brats, who happened to be supernatural, and who

could not get along. A universe run by lust, caprice, cruelty, and revenge. But

today, we know exactly why the seasons occur.

“The

Return Of Persephone”

(credit: Frederic

Leighton, via Wikimedia Commons)

The classical Greeks

also accepted that their ancestors had been much stronger than they were.

Repeatedly in The Iliad, heroes hoist rocks that “no man today

could lift,” and they do it with ease.2 In such a universe,

ideas that were right in one area or era might be quite different from those that

were right (in both senses of right) in some other distant land or

era.

In the modern view,

under Science, we assume that laws describing the strong force, the weak force,

electromagnetism, and gravity apply everywhere and always have done so. It is true

that we have not yet found a way to translate our model of gravity into the

system of ideas and equations that describes the other three, but we are

confident that a unified field theory does exist. Ours is a single coherent

universe, we assume.

Do most people in our

modern society truly believe the universe is one coherent system? Yes. That

view is the view that Science begins from. The alternative – superstition – is

simply not palatable for most people in the West today. Whatever the flaws in

the current scientific worldview – and it is not logically airtight, as we have

seen – we’ve nevertheless seen it achieve far too many successes to gamble on

any of its superstitious alternatives.

People in the West today,

by and large, do not take a sick child to a shaman for treatment. They go to a

Western doctor. Who today would try to fix his broken-down vehicle by casting

pennies, burning incense sticks, or chanting? Farmers everywhere look to

agricultural scientists for advice on which crops to grow on their farms and

which fertilizers to use. In today’s world, for better or worse, we live in the

Age of Science. The evidence says that heeding Science is a smart gamble, a

solid Bayesian choice, therefore, a fully rational one.

Let’s keep this first

implicit assumption of Science in mind: in this universe, all is connected to

all else in a coherent way. (Maxwell discusses this view and its problems at

length in his book From Knowledge to Wisdom, pp. 107–109.) 3

However, and in the

second place, we also now know that this universe is a kind of aware. Changes

in any part of the universe produce changes in other, distant parts – instantly.

Like a school of hundreds of fish or a flock of thousands of birds, or a single

animal body, turning as one, the parts of the universe connect in amazing

ways.⁴ How the parts are connected is still a mystery to physicists, but that

they are connected is no longer in doubt. Quantum Theory tells and shows us

this is so.

Quantum Theory tells

us that the actions and reactions that connect sub-atomic particles are instant. Reverse the

spin of one here, and its partner particle – untouched by anything – will

reverse its spin at that same instant even if it is on the other side of the

universe. And the information passes from a particle to its partner instantly.

Not at the speed of light, which Einstein argued was the speed limit of the

universe, but instantly.

Physicists call this

relationship of all particles in the universe entanglement. Physicists

have proved that it is the case as surely as they have shown that the laws of Newton

are human-scale approximations of Relativity. (Josh Roebke describes this

research in an article published in 2008.)5

Here again, we must

make a choice as to which model to use as we interpret the most recent data

from Physics. The evidence supports the idea of entanglement. If we poke it in

one place, it sometimes reacts in another very distant place, and it does so

instantly. Because it does, we may choose to view it as being not just coherent,

but a kind of conscious. The universe feels itself, all over, all at once, all

of the time.

And let us remind

ourselves here that the quantum view of reality in some of its other aspects also

feels like life the way we live it. It grants us a degree of free will. It

allows me to rationally hold people responsible for their actions.

In reality, the big

majority don’t of us live daily life as if the cars around us are particles

driven by unchangeable forces toward inescapable outcomes. Cars contain drivers

who are responsible beings. If they aren’t, they shouldn’t be driving. If your

car drifts out of its lane, and I have to steer sharply left and almost swerve

into oncoming traffic, I’m going to be mad at you, not your car. (Get off your

cell phone!!) Similarly, I reject any moral code that excuses felons as not being

responsible for their actions. Belief in Quantum Theory makes this kind of

reasoning rational. Daily life is now corroborated by Physics.

Thus, it is rational

to accept this second assumption at the base of our thinking and choose to see

our universe as a single system that is also conscious.

But if we see our

universe as being both coherent and conscious, are these two

choices together enough to justify a kind of theism? No. We need one more idea.

The third big

background idea in the case for my thesis is the one this book has labored long

to prove. It is the belief that there is a moral order in this universe, a

moral order that is observably, empirically real.

The universe runs by

laws that cause patterns in the flows of physical events. Our cultural values

guide us, as tribes, to sail through the universe’s patterns. These values were

learned through trial and painful error by our ancestors over thousands of

years. People who live by these values survive. Those who don’t, don’t.

History is filled with evidence showing values are real.

Courage. Wisdom. Freedom.

Love. Our words for our values name patterns of long-term movement in the

universe and, therefore, are as real as gravity.

Again, we can ask

about this third big idea: “As opposed to what?”

The idea usually

opposed to moral realism in our times is moral relativism. In its view, values

are only tastes, and right and wrong depend on where you are. The moral

relativists say that what was right in Rome in the first century is not morally

right today; what is right in East Africa is not right in Western Europe. And

there are no facts to be found or general conclusions to be drawn about what

right is. For the moral relativists, no values can be shown to be grounded in

what is physically real.

Under the moral

relativists’ thinking, there can be no peaceful way to resolve disputes between

different cultures because there is no common ground on which to even begin the

negotiations.

In this view, I have

argued, they are mistaken.

Material reality is

the common ground, and we can show that values are based in material reality.

Then, we can debate how to interpret the data we observe about ourselves, build

models of how human societies work, and test our models against the evidence of

History. Finally, we can devise a rational model, that does explain us, test it

constantly, and use it to settle our disputes peacefully.

The only things

stopping us from creating and maintaining a prosperous world at peace are the

anti-morals: cupidity, laziness, bigotry, and cowardice.

Now, add all of these

three big ideas together.

The universe is coherent.

The universe is

conscious.

The universe is

compassionate.

If, as a modern human

being in touch with the basics of Science in all its forms, I believe the

universe is a single coherent thing – even if we do not understand all its laws

– and I further believe it is conscious – even if its consciousness is so vast

that humans have barely begun to comprehend it – and I further believe it is

morally responsive – even if its moral quality is only discernible in the flows

of millions of people over thousands of years – if I believe these three

claims, then in my personal way, I do believe in God.

What? That’s it?

Yes, my patient

reader. That’s it. I do still believe in God. My view is a pretty lean one. No

sacred texts, no holy men, no miracles, no rituals. But every instinct in me

tells me that it is a wise, sane, Bayesian gamble at the base of my thinking

where I must gamble on something if I am to stay sane. I can't be neutral or objective

about the roots of my own sanity.

And as far as the leanness

of this kind of theism goes, I would say such is life. Adults have to get by on

leaner fare than do children who seek a bearded man in the sky. For adult

citizens in a democracy, life is labor and hazard much of the time. But the

best consolation of adult life is the firm belief that the patterns that we see

in the flows of events in the world – even patterns that only show in the

evidence of centuries of human actions – are real. Your deep

intuition that good and right are real is not naïve or crazy. It is the sanest

belief you have.

So now, in a personal

response to the case presented so far, let me try to show in my next chapter

that this case is enough to support a belief in God. And personal is

the word to use to describe my next chapter. It has to be personal. It has to

make the personal universal and the universal personal.

Notes

1. Dennis Overbye,

“Laws of Nature, Source Unknown,” New York Times, December 18,

2007. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/18/science/18law.html?

pagewanted=all&_r=0.

2. Homer, The Illiad (c. 800–725 BC; Project Gutenberg),

p. 91. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6130/6130-h/6130-h.html#fig120.

3. Nicholas

Maxwell, From Knowledge to Wisdom: A Revolution for Science and the

Humanities (London, UK: Pentire Press, 1984), pp. 107–109.

4. http://www.wired.com/2013/12/secret-language-of-plants/

5. Joshua Roebke,

“The Reality Tests,” Seed magazine, June 4, 2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.