Chapter 9 The Mechanism of

Cultural Evolution

In order to build a universal

moral code, we must now do two things: first, explain how moral codes get

established and amended; second, extract from our best modern models of the

physical universe the principles that we should use to guide us in building a

moral code so that it is consistent with, and not disconnected from, all of our

other knowledge in modern times. We need to make our ideas of Good fit with our best ideas of Real.

All of us are raised to be

fiercely loyal to the way of life that we grew up with so we can expect that

analyzing the roots of morality will be difficult. Powerful and subtle internal

programming will steer us toward affirming the morals and morés that we grew up

with. But difficult does not mean impossible. Most importantly, we have the

evidence of history and of life as it is lived by real people in real societies

today to check our theories against.

And what do we notice about moral

code systems if we closely analyze various human “ways of life”, namely the

cultures of a variety of human societies, present and past?

Human beings baffle each other

and each one sometimes even baffles himself. Why do we do the things that we

do?

The reasoning process which

answers this question contains several steps. To begin with, we can analyze the

everyday actions of the people around us. Why does this man get up when his

alarm clock rings? Why does he even have an alarm clock? Why does this woman

shampoo her hair and then dry it with a hot-air blowing electrical device? In

similar ways, dozens of mundane questions may be posed about the everyday life

of our society or any society. These “ways”, of course, seem obvious to the

people who live in the society in which the ways are practiced. There they seem

simply to involve people being people. But to people in other cultures, the

ways are not merely unobvious; they’re unknown.

Another interesting ordinary

example of a custom that is commonplace in some societies but not others is the

custom which trains men to shave their beards. In some cultures, men who are

clean shaven are seen as being neat, presentable, and attractive. In other

cultures, a man without a beard is seen as being weak or irreligious. In some

cultures, men are forcibly shaved as a mild form of punishment. The fascinating

questions come when we begin to ask “Why?” Why shaving? Is there some survival

advantage in some environments for men who were trained by their fathers to

shave their beards? For example, do men who shave daily appear younger/more attractive

to women? Do they reproduce more successfully and prolifically and thus pass

their ways on to more progeny?

Research on such shaving

questions is sparse and inconclusive. However, what is important in our context

is to see that the beginning of the critical way of thinking about cultural morés

and customs in terms of their potentially advantageous roles in the

evolutionary survival game is the beginning of our thinking about, and analyzing,

our “ways”(morés) scientifically. Under this view, none of our “ways” are

trivial or meaningless. They all matter. Under this view, the mundane rapidly

becomes the fascinating.

If we keep asking why, the

answers seem to spread further and further from each other into various human

morés and then cultures; human morés vary widely within any given society and

much more so from society to society. But if we persist in analyzing masses of

the evidence, patterns begin to emerge. Based on these patterns, we can make

some general statements about people and their ways. For the most part, people

act in the ways that they do because they have been programmed to act in those

ways by their parents, their teachers, and the communications media of their

cultures.

People don’t simply relieve even

pressing, short-term physical needs. Even actions that at first glance seem to

be driven purely by the individual’s bodily functions the vast majority of

humans learn to perform in ways that are considered socially acceptable in

their own cultures.

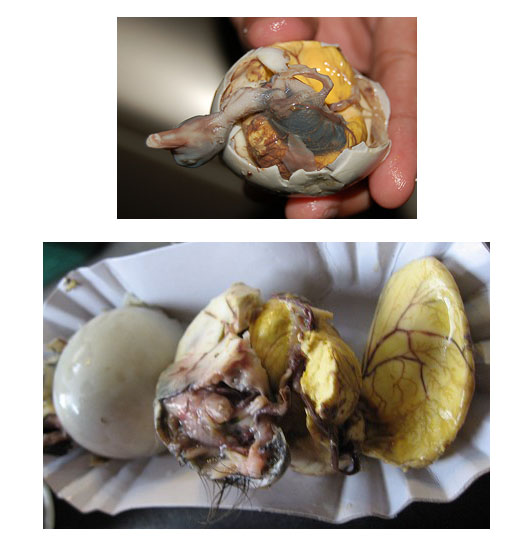

Balut - soft boiled fetal duck (commonly eaten in Vietnam)

I

eat, but I far prefer to eat dishes with which my upbringing has made me

familiar. I also wash my hands before eating to cleanse them of disease-causing

germs which I might otherwise ingest with my food if I ate it with grubby

hands. I’ve never seen these little animals, but I have been trained by the

mentors of my society to be wary of germs; consequently, I take measures to

neutralize the danger that I believe they pose to my well being. I also make an

effort to urinate and defecate only in places deemed acceptable in my society,

no matter how urgently “nature calls”.

staphylococcus bacteria (common on human hands)

A fact that it is important to

stress here is the profound way in which human behavior patterns differ from

those of nearly all other animals. A turtle need not ever see another turtle,

from his hatching to his dying of old age, in order to be “turtlish”. Alone, a

turtle would be unable to complete all of the reproductive behaviors that his

body’s genetic programming would be prompting him towards each mating season,

but in a lonely way, he would at least try to search for a mate. The rest of

the time, he would live in ways that are completely normal for turtles,

entirely directed by his body’s genetic code.

“Lower” animals such as crabs, ants, and fish clearly are more fully programmed by their genetic codes than

are “higher” ones. But even the “higher” animals learn only small portions of

their behavioral repertoires. Kittens, in time, will stalk balls and then mice

and birds, even when taken from their mothers still blind and helpless. This is

genetic programming of behavior. Humans, by contrast, if raised by animals,

such as dogs, become humanoid dogs, and demonstrate hardly any “human” behaviors

at all. We humans – unlike turtles, apes, and kittens – learn how to be "humanish"

by the process known as "enculturation", almost entirely from other,

older humans. (1.) (2.)

Most animal behaviors are

instinctive, programmed into animals genetically, especially in the “lower”

animals. As we rise up the scale of complexity, we arrive by degrees at humans,

in whom most behaviors are programmed by nurture, by their upbringings in other

words. Together, these behaviors – along with the body of knowledge that a community

of humans consults in order to judge when to apply specific behaviors in

response to real life situations, how to perform the behaviors, and then how to

verify that each behavior has been done appropriately – form what is called the

“culture” of that human community. Put a dead fish in the ground with each corn

seed that you plant and wear your tuxedo and black tie to the opera.

The first large step on our

journey toward the answer to our question about humans and their ways then is

simply this: humans behave in the ways that they do because their patterns of

behavior are programmed into them by the adults around them in their formative,

early years.

Notes

1. http://www.learnstuff.com/feral-children/

2.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enculturation

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.