Chapter 11 Part E

The one significant interruption

in this process is the one called the Romantic Age. The meaning of this time is

still being debated, but in my model which sees a kind of cultural evolution in

the record of human history, there are only a couple of interesting points to

note about the Romantic Age (roughly, the 1790's to about 1850).

"Abbey in an Oak Forest" by C.D. Friedrich

(showing imagination and emotion of the Romantic Age)

First,

it reaffirmed and expanded the value of the individual when the Enlightenment

had gone too far and made duty, duty to the family, to the group, or to the

state, seem like the only “reasonable” value that should motivate human beings

as they chose their actions. Romanticism asserted forcefully and passionately

that the individual had an even greater duty to his own soul. I have dreams, ideas,

and feelings that are uniquely mine and I have a right to them. Paradoxically, this philosophy

of individualism is very useful for a society when spread over millions of

citizens and over decades and generations, as was mentioned above, because even

though most of the dreamers allowed to rove produce little that is of use to the larger

community, a few create beautiful, brilliant things that pay huge material,

political, and artistic dividends.

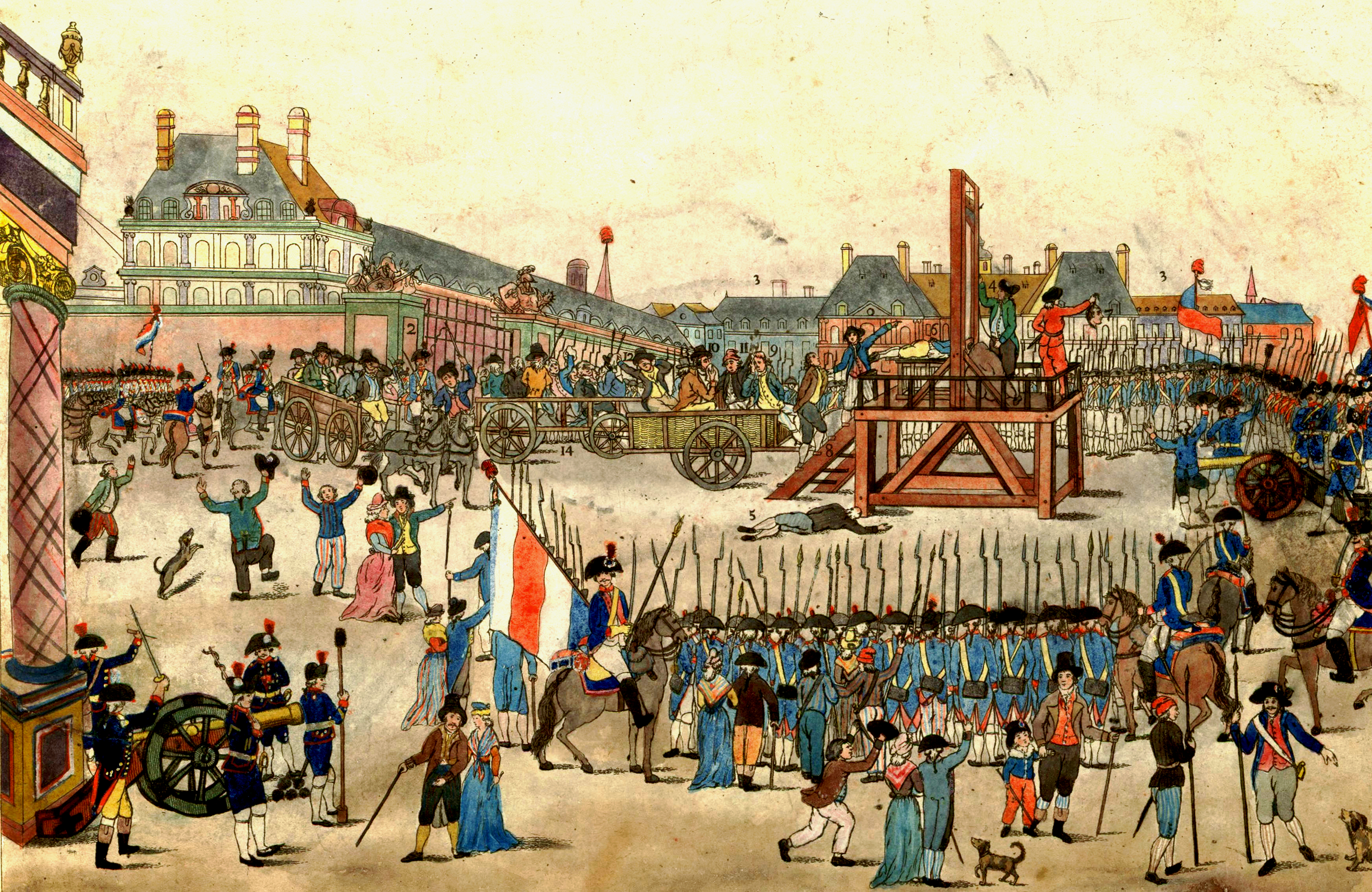

drawing of guillotining during French Revolution

In

the second place, it is important to note that as a political philosophy,

Romanticism produced some painful excesses. The citizens in France and

elsewhere were indeed passionate and excited about their ideals of liberty, equality,

and brotherhood, but they did not know how to administer a state and so, in a short

while, they simply traded one autocrat for another. Their struggle to reach a

"reasonable" view of what human beings are in their deepest nature

and how a system of government that resonates with that nature may be

instituted among humans took longer than one generation to evolve. But it did come,

or, rather, the French began evolving toward it and are still evolving as I

write, as are we all.

photo of aftermath of Battle of Gettysburg, 1863

Even

in the U.S., the idealism of the American version of the Romantic revolt against duty and discipline, in awkwardly attempting to integrate the ideals of reason, order, and good governance (i.e. Enlightenment ideals) with more spiritual ones

that asserted the value of every individual human being, produced the painful

excesses of genocide of the native people, enslavement of millions of Africans,

and the horror of horrors, the U.S. Civil War.

America had to undergo some very

hard adjustments before she began to integrate the Christian belief in the

worth of every individual with the need for order and the sense of duty that enabled every individual to allow every other individual to live his or her life in the way

he or she chose to. But the slaves were freed, and the government began to compensate the native people (with reserves of land and cash) and take them into the American mainstream (with

opportunities for Western-style educations), or rather, to be more honest, the Americans began moving

toward these ideals more and more determinedly, and continue to do so until

this era.

Thus, in the larger picture of

all of these events in the history of the Western nations, the upheaval called

the Romantic Age wrote into the Western values system a greater willingness to

compromise and a deeper respect for the institutions of democracy. Belief in the institutions of democracy, people could see, was all that was keeping their various states from devolving into complete chaos. Democracy

was, and is, our best hope for creating institutions by which people may use

reasoned debate instead of war to find a balance between the security-loving

conservatism of the establishment and the heated passions of the reformers in

each new generation.

In short, once again, a kind of synthesis evolved. In a compromise, two opposing camps each have to give a little of

what they like in order to get a little more of what they want most of all. But

what really happened at the end of the Romantic upheaval was more like what

Hegel calls a "synthesis", a workable melding between a thesis and

its antithesis began to grow. And we can go beyond Hegel and say that it just wasn't a synthesis that any science of history - Hegel's or anyone else's - could have foreseen. Rather, as conditions changed and old cultural ways became obsolete, a new, opportunistic species of society arose.

Occupy Wall Street protesters, New York, 2011

The very idea of democracy evolved till it made the protecting of the rights of every individual

citizen the most important reason for its own existence. All of this from the melding of

Christian respect for the value of every single human being, Roman respect for order

and discipline, and Greek love of the seer, the one who can question the forces

of the material world. Participatory democracy was the logical outcome of the

Renaissance and Enlightenment world views being applied - in several

successively more profound stages - by human societies, to themselves. The adjusting

just took a while. And it goes on.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.