Chapter 12 The Mechanism of Cultural Evolution

geisha dancers

(credit: Joi Ito, via Wikimedia Commons)

dabbing

(credit: Gokudabbing, via Wikimedia Commons)

In order to begin to build

a universal moral code, we must now create a model of human cultural evolution.

One that is reasonable and testable, as all theories in Science are supposed to

be. In order to set up such a model, first, we must describe some data, i.e. in

this case, tell in a general way how a number of morés and customs have

operated in the daily life of several different nations. Second, we must extract

from our observations of data, a theory of how the moral codes that underlie all

human tribes work, i.e. what the software behind human tribal behavior looks

like, how parts of it evolve, and how, sometimes, parts fade out. Then, to

complete this part of our argument, we will test the theory.

The testing of our

theory will have to be ex post facto. That is, we could never intentionally

program a new moral code into a test population even of a few hundred people

just to see how, over a dozen generations or so, that code affects their

survival rates. That would be morally forbidden under the code of ethics we in

the West live by now. We can’t purposely, consciously usurp the freedom and

dignity of other people for reasons of research. But we can examine the records

we have of human tribes, their explicitly stated values and beliefs, and the

choices people in those tribes make and have made in real life. In short, we should

be able, through the study of History, to explain why we humans do the things

we do.

Most of us are raised

and conditioned to be fiercely loyal to the way of life we grew up with, so we

can expect that analyzing the roots of morality will be hard. Powerful, subtle

mental programming steers us away from any such analyzing and toward affirming

the morals and morés that we grew up with. But “hard” doesn’t mean “impossible”.

Most importantly, we have a lot of evidence of life as it has been lived by

real people – i.e. History – to check our theory against.

To begin with, we can

observe the everyday actions of the people around us. Why does this man rise

when his alarm clock rings? Why does he even own an alarm clock? Why do men in

some cultures shave off their beards? Why have women in so many cultures for so

long been so unjustly oppressed? Why is honoring elders such a widespread

custom?

In similar ways,

dozens of mundane questions may be posed about everyday life in our society or

any society. While these actions and the motivations behind them may seem

obvious to the people who live in the society where they are practiced, to

people in other cultures, the reasons for foreigners’ ways aren’t so much

confusing as inscrutable. To outsiders, no nations’ ways are normal.

dancers in West Africa

(credit: Eric Draper, via Wikimedia Commons)

An interesting

example of a custom that is commonplace in some societies but not others is the

one that trains men to shave their beards. In some cultures, clean-shaven men

are seen as being presentable, neat, and attractive. Socially acceptable. In

other cultures, a man without a beard is seen as being weak.

The fascinating

questions come when we ask “Why?” Why is shaving done? Is there a survival

advantage in some environments for men who learned from their fathers to shave

off their beards? For example, do men who shave daily appear younger and, thus,

more attractive to women? Do they reproduce more prolifically and thus pass

their shaving behavior on to more progeny, i.e. sons who watch them shave and

so do the same themselves one day?

Research on shaving

is sparse and inconclusive. However, what’s important to see for now is that

asking these kinds of questions about cultural morés and customs in terms of

their possible advantages in the survival game entails thinking scientifically

about morés. Under this view, no human actions are trivial. They all have

significance in the larger design of a culture. Under this view, we also can

compare cultures; then mundane customs become fascinating.

If we keep asking

"Why?" about our "ways of life", the answers seem to spread

further and further from one another into a great variety of human morés and

then whole cultures; human morés vary widely within any given society and then much

more so from society to society. But if we persist in analyzing our observations

of human behavior, patterns begin to emerge. Based on these patterns, we can

make some general statements about people and their ways.

For the most part,

people act in the ways that they do because they have been programmed to act in

those ways – by their parents and their teachers, and then by the media in

their cultures. Humans don’t anywhere come by their “ways” by genetic

programming. We are not born to adopt shaving our beards or speaking English or

cooking our food because of any “innate” forces pushing us to do these things.

They are learned from those around us as we develop in childhood.

For example,

close observation shows that the vast majority of humans early on in their

development learn to urinate and defecate in ways considered socially

acceptable in their particular culture.

Balut (soft-boiled fetal duck, Vietnam)

(credit: Marshall

Astor, via Wikimedia Commons)

In this category of

mundane morés, we also find the morés that govern how we eat. I far prefer

to eat dishes I find familiar, ones I ate during my upbringing. And in my

culture, I wash my hands before eating in order to remove disease-causing germs

I might otherwise ingest with my food if I ate it with dirty hands. I have

never seen these tiny animals, but I have been trained to be wary of them.

Therefore, I take measures to neutralize the danger I believe they pose to my health.

For similar reasons, I try to urinate and defecate only in places deemed

acceptable in my society, no matter how acute my natural urges feel.

It is crucial to note

here the profound way in which human behavior patterns differ from those of

nearly all other animals. A turtle need not ever see another turtle, from

hatching to dying of old age, in order to be turtlish. A turtle would not be

able to perform its genetically-driven reproductive behavior alone each mating

season, but it would at least try to find a mate. The rest of the time, it

would live in ways completely normal for turtles, with all its behaviors being entirely

directed by its body’s genetic code.

Creatures like ants,

crabs, and fish that came early in evolutionary history clearly are more fully

programmed by their genetic codes than higher order ones like cats, dogs, apes,

and humans. But even most large, complex animals learn only fractions of their

behavioral repertoires. Most of their behaviors, in other words, are

genetically programmed. Kittens, in time, will stalk balls and then mice and

birds, even if they are taken from their mothers still blind and helpless.

Puppies are genetically programmed to bury bones.

Humans, by contrast,

if raised by dogs, become doggish, and demonstrate few if any human behaviors.

We humans – unlike turtles, apes, and kittens – learn to be our society’s way

of being human by “enculturation,” i.e. almost entirely from other, older

humans.1,2

Most animal behaviors

are instinctive, programmed into animals genetically, especially in lower-order

animals. As we rise up the scale of complexity, we arrive at humans, in whom

most behaviors are programmed by nurture – by their upbringings, in other

words. The knowledge base that you consult in order to respond real-life

situations is called your culture and it is learned, not innate. Put a

dead fish in the ground with each corn seed that you plant; wear your tuxedo

and black tie to the opera. These are customs, not inherent ways.

Mom teaching daughter to cook

(credit: Sgt. Sinthia

Rosario, via Wikimedia Commons)

But if humans act as

they do mostly because of social programming, then we must ask why or how some

behavior patterns ever became established at all in the earliest human

societies? And why many behaviours possible for humans vanished or never got tried

at all? Why don’t most people on this planet eat holly berries or make their

children into slaves? The answer is clear: we keep the morés that help us to survive;

we drop the ones that don’t.

We keep alive those morés

that keep us alive. That will be our hypothesis.

Behavior patterns get

established in a society and passed on, generation to generation, if they

enable the people who use them to live, as individuals and tribes – to survive,

reproduce, and then program the behaviors into their young. If new morés or behavior patterns are to last, then they must

achieve these results at levels of efficiency at least as high as those the

community knew before its people began to try out the new behavior patterns. When

an old moré no longer serves any of its carrier society’s needs, or in fact is

getting in the way of serving survival needs, then it dies out. This is the

theory around which the model of sociocultural evolution is built.3

Understanding the

process by which a new moré enters into the cultural code of a society is vital

to our understanding the survival of morés themselves. None of the phases in a

society’s adopting a new moré necessarily entails any of the others. A behavior

recently acquired by one person on a trial basis may make that individual

healthier and/or happier, but this does not automatically mean he will

reproduce more prolifically or nurture his kids more effectively or teach his

morés to them more efficiently. Other factors can, and do, intervene.

Many examples can be

cited as evidence to support this model. Some tribes in Indonesia once taught

every member of the community to go into the forest to defecate. The individual

had to dig a hole in the earth, defecate in it, then cover the excrement with

earth before returning to the tribe’s living spaces. The “reason”? Children

were taught to hide their excrement so no shaman could find it and use it to

cast an evil spell on such a careless child or his/her family.4

In the view of most

of us in Western societies, the advantages of the practice lie in the way it

reduces the risk to the community of diseases such as cholera. We know by our

Science that excrement carries microbes. Sometimes deadly ones. Similar

practices are taught to people in Western societies (and described in cultural

codes as early as those found in the Old Testament of the Bible).

Or consider another

of our morés. For centuries, many Europeans drank a lot of tea, hot chocolate, and/or

coffee. These customs rapidly became accepted as “traditional”, even though the

dates of their introductions into Europe can be specified to within less than a

decade. Neither tea nor coffee was a traditional beverage in old European

cultures. Scientific reasons for why consuming them was beneficial to human

health were not known until germ theory was found, but the benefits were felt

by their enthusiastic consumers, nevertheless.

In much of Europe,

local water contained dangerous bacteria. But the water for properly-made tea

is always boiled before the tea is brewed. Boiling kills the pathogens. Tea

drinkers gained a modest, but real, survival advantage over those who did not

like boiled beverages.

While the benefits

were mixed because they were offset by the negative effects of caffeine abuse,

the important thing to see is that these people did not need to know anything

about bacteria in order to arrive over generations, by trial and deadly error,

at a custom that enabled them to survive in greater numbers over the long term.

Tea drinkers died much less often during epidemics. Of course, in China, the

drinking of tea had been looked on as a healthful practice for both the

individual and society for centuries by the time Western cultures arrived at a similar

custom.

(credit: Docteur Cosmos, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Innu

grandmother and granddaughter

(credit: Ansgar

Walk via Wikimedia Commons)

Another example of a

moré that guides our cultures can be found in a different area of life, in the

laws of Moses. One of these instructs followers of the Hebrew, Christian, and

Muslim faiths to “Honour thy father and thy mother, that thy days may be long

in the land that the Lord thy God hath given thee.” (Exodus 20:12) The faithful

are instructed to care for, respect, and consult their parents. Therefore, by a

small logical extension, all citizens of the community should be cared for in

their old age.

Honoring our elders

means consulting with them on all kinds of matters. But why did this custom

have a good survival index?

Before writing was

invented, an old person was a walking encyclopedia to be consulted for useful

information on treatment of diseases and injuries, planting, harvesting, and

preserving food, making and fixing shelters and tools, hunting, gathering, and

much more. Knowledge was passed down the generations by oral means. By honoring

elders, the people of a tribe preserved, and thus had access to, much larger

stores of knowledge than if they had simply abandoned their elderly as soon as

they appeared to be a net drain on the tribe’s resources. An elder’s knowledge

often solved small problems or, sometimes, major crises, for the entire tribe.

Over many generations, societies that respected and valued their elders

gradually outfed, outbred, and outfought their competitors.

Imagine an elder in a

primitive tribe. She might very well have said: “We have to boil the water.

This sickness came once before, when I was seven summers old. Only people who

drank soup and herb tea did not get sick. All who drank the water got sick and

died.” Honoring elders is a tribe-saving policy. It is, every so often, the

difference between life and death for the whole tribe.

Secretary Sibelius, Joplin MO (2011)

(credit: By HHSgov,

via Wikimedia Commons)

It is worth noting

that the fifth commandment in its original wording read, “Honor thy father and

thy mother, that thy days may be long …” and so on. “Thy” days, not

“their” days. At first glance, this seems odd. If I honor my parents, they will

likely enjoy a more peaceful and comfortable old age, but that will not

guarantee anything about my own final years. By then, my parents, even if they

are grateful folk, will most probably be long since dead. At that point, they

can’t do much to reciprocate and so to benefit me.

On closer examination

though, we see there is more here. As we treat our elders with respect in their

last years, consult their opinions on a range of matters, include them in

social functions, and so on, we model for our children behaviors that are

imprinted on them for a lifetime, and they, in turn, will practice these same

behaviors in twenty years or so. They will take care of mom and dad. Dad. Me. The

commandment turns out to be literally true.

Note also that there

is a complex relationship between our morés or patterns of behavior and our

values programming. The common behavior patterns in a culture, patterns that we

call morés, are just ways of acting out in the physical realm

beliefs that are held deep inside each individual’s mental realm, beliefs about

what kinds of behavior are consistent with the programmed person’s moral code,

i.e. her/his code of what acts are right or wrong, appropriate or

inappropriate, sensible or silly. More on these matters as we go along.

Honoring parents

enables an increase in the tribe’s total store of knowledge. Not committing

adultery checks the spread of sexually transmitted diseases. It also increases

the nurturing behaviors of males, as it increases each man’s confidence that he

is the biological father of every child he is being asked to nurture. Not

stealing and not bearing false witness have benefits for the efficiency of the

whole community, in commerce especially.

By this point in our

argument, explaining the benefits of more commandments, traditions, and customs

should be unnecessary. A major fact is becoming clear: a moral belief and the

behaviors attached to it become well established in a tribe if the behaviors

help tribe members who practice them to survive. It is also clear that

individuals usually don’t see the long-term picture of the tribe’s survival.

They just do what they were raised to believe is right.

A retrograde custom in modern

times: child labor, Nepal, 2010

(credit: Krish

Dulal via Wikimedia Commons)

Children may not

enjoy some of the behaviors their elders dictate; they may not enjoy them later

when they are adults. Work is hard. Building shelters is work. Making clothes

is work. Gathering food and preserving it for the winter is work. Raising kids

is work. But for survival, individual happiness is not what matters. Patterns

of living that maximize the resources of the tribe over many generations are

what matter, and these ways of living do not always make sense to the people

being programmed to do them. But tribes that do not teach hard work as a virtue

die out.

To illustrate

further, another example of a custom that seems counterintuitive to Western

minds, but that works in some contexts, can be offered here. Polyandry allows

and encourages one woman to have two or more husbands, legally and with the

blessings of the community. It seems counterintuitive to us in the West. But

the practice is not only viable in some cultures, it even promotes better

survival rates. In some areas of the Himalayas, when a man knows that finding

work may require him to be away for an extended period, he can pick a good

second husband for his wife. Then he will know that she, his children, his

property, and children and property of the other man, will all be protected. If

she becomes pregnant while he is away, it will be by a man he has approved of.5 As

long as all three really are faithful to the marriage, the risks of any of them

getting an STD remain small. More surviving children is the result.

All that has been

said so far in this chapter has been supporting this hypothesis: a concept,

belief, or value and the behaviors that it fosters get well established in a

tribe if the value/belief – with its attached behaviors – improves the odds of

its adherents’ survival.

A side-note is in

order here.

This train of thought

on the long-term purposes that morés serve for human tribes also brings us to

an implication deeply embedded in our argument. Close analysis of individual

human behaviors reveals that some of them can’t be completely explained by our looking

at their long-term advantages for the tribe.

We can’t reason our

way to a moral code for all humans until we accept that humans are capable of

noticing patterns in their environments. Re-occurring patterns. We call our

labels/words for patterns concepts. In short, we have to incorporate into

our argument the idea that humans are capable of conceptual thought, what we

usually call “reason”.

Our ways of life are

not just the results of the forces in physical reality. Rather, human ways of

life are mostly made of our creative responses to stressors in reality. No

model of cultural evolution is going to prove adequate to explain that if the

model does not see humans as thinking beings. Humans think in concepts.

Comparing mental

models of things is what we do when we think. When I think of cats, I

mentally form a concept of “cat”. But I never have a cat inside my head. Or a tree

or a nail or any physical thing. And in reality, there are no trees. There are

living things that exist by photosynthesis that I find it convenient to call

“trees”. But each is an individual living thing. And they differ from each

other. Coniferous, deciduous, bushes, bamboo, banyan, and so on. We make up the

terms we need in order to sort memories of real-world things for purposes

useful to us. But reality contains no trees. On the other hand, I can use the

concept of a tree to escape wolves. Sometimes, I may urgently need that

concept.

Thus, I think with

concepts of things, and I am capable of forming conclusions by a process that

can’t be explained in strictly mechanical ways. The “I” that is most “I” is not

made of cats or trees. But I can think about those things and many others and

reach useful conclusions. That is just human.

We humans act much of

the time in ways that our cultures have programmed us to act, but we also can

figure some situations out for ourselves and try new responses to them. We can

learn on our own. Sometimes, creative individuals even add new concepts that get

accepted into their tribe’s whole culture. They win a lot of others over

to drinking tea or washing their hands before eating. The subculture that the

converts form then out-survives those who don’t accept the new custom, and in a

generation or two, the custom is customary.

Behaviorism’s model

of how humans think is left behind at this point in our argument because it does not take into account

how we think. It pictures stimuli and responses as being connected in a

one-to-one, mechanical way. It then uses mechanical terms to explain individual

human behaviors. But in the real world of real

human beings, this model doesn’t work very well.

The behaviorist

reports that “The organism sees specific colours and shapes (or hears certain

sounds), pushes the bar, and gets the food-pellet reward.” For example, a rat

sees a light go on in its cage, presses the bar it has learned by trial and

error to press, and gets a food pellet. Behaviorists say people do the same: go

to work at the factory, punch a time card at the clock beside the door, put

bolts on widgets for nine hours, punch out, collect their pay, and go home.

This picture of activity, Behaviorists say, portrays how all learning and doing

works for all living things – including humans – all the time.

Bull Moose (credit: Ryan

Hagerty, Wikimedia Commons)

But a human can

confront situations that are not, by sensory evidence, like anything the human

has ever encountered before, and still the human can react effectively. The

English hunter who had never seen a moose, kangaroo, or rhinoceros in muskeg,

outback, or veldt still knew where to shoot to kill one.

Polynesian sailors

navigated well by the stars of a new hemisphere when they first came to Hawaii

as did European sailors when they first began to explore the seas south of the

equator. In each of these situations, they were guided by a set of concepts – ideas

based on patterns found in large numbers of experiences. For example, a mammal’s

heart lies at the bottom of its ribcage, just to the left of center, and a

heart shot is fatal for every animal on this planet.

Furthermore, a man

may react one way to a new stimulus in his first encounter with it and quite

differently in his next encounter, after he has thought about the stimulus situation

for a bit longer. He sees a deeper, more general pattern that he recognizes,

and then, based on concepts stored in his memory, he plans and executes a

better response to it. Behaviorism can’t explain such acts.

Nearly every human

past the age of ten is capable of forming generalizations based on what he has

learned from his individual experiences and, to an even greater degree, what he

has been taught by the adults of his tribe. Conceptual thinking is as human as

having forty-six chromosomes. It comes naturally to a child at about seven

years of age when, for example, he realizes that the short, wide cup holds more

soda than the tall, slim one. Volume is a concept. (I take Piaget as my guide

here.6)

The programmers of

society – parents, teachers, shamans, and others – make use of this faculty in

their young subjects, greatly increasing these children’s chances of surviving

by programming them with more than simple, one-to-one responses to common, recognizable

sense-data patterns in the tribe’s territory. The young subject is programmed

with concepts and then, at higher levels of generality, with principles,

beliefs, and values. These enable that young subject to respond

to, and handle, new situations. Recognize that a new animal or plant can be

used for food. Or recognize that a new animal or plant is harmful. (“This snake

or spider probably has a poisonous bite; many of their kind do.”)

Our capacity to

think, to use concepts, gives us an advantage over other species on this

planet. Thus, this human capacity to think in concepts, combined with our

capacity to communicate, is the main factor that enables cultural evolution.

A thinking individual

can imagine a new way of getting food, chipping flint, or curing a disease,

then tell it to her/his fellows. A few try the new way. If it works, and it’s

not threatening some other moré that is “sacred” for the tribe, the new moré

gets taken up. The tribe evolves. Not by genetic variations, but by cultural

ones, i.e. by acquiring in the whole tribe a new concept that gets good results.

Reindeer with herdsmen

(credit: Detroit

Publishing Co., via Wikimedia Commons)

Every tribe has

labels (words) for large groups of similar things or events in the tribe’s

environment. These category terms are taught to the young because they are useful

in the quest for survival. The Sami (Laplanders) have many words for describing

a reindeer because they sometimes need to differentiate between them. A single

word to describe a blond, pregnant doe is useful if she is in labor and needs

immediate aid. And for Neolithic tribes, it probably was useful to have many

terms for rocks – like “flint” – because only certain types of rocks, i.e. flint,

could be used to make effective weapons and tools.

By contrast, most

visitors to Lapland speak only of reindeer does, bucks, and fawns, and some

visitors may have no words for reindeer at all. Most of us today, compared to

our Neolithic ancestors, know little about types of flint.

The word principle is

a term for patterns that are common in even larger groups of things. Terms

like danger and edible name general

principles that a tribe has spotted in many experiences of many members. Terms

for principles are harder to learn than ones like tiger or fruit,

but worth learning because they are very useful in the real world. The

term danger enables tribe members to tell one another quickly to

get away from something. It covers crocodiles, tigers, snakes, bears, unstable

cliffs, quicksand, poison ivy, bad water, etc. It’s an efficient term so it is

worth learning and keeping. I avoid snakes on principle.

The term edible covers

nuts, berries, maggots, eggs, frogs, fish, lizards, and many more things an

individual may come upon within the tribe’s environment. It enables one tribe

member to tell another that the thing they’re looking at is worth gathering

because it can be safely, nutriciously eaten.

California spiny lobster

(credit: Dr.

Kjaergaard [assumed], via Wikimedia Commons)

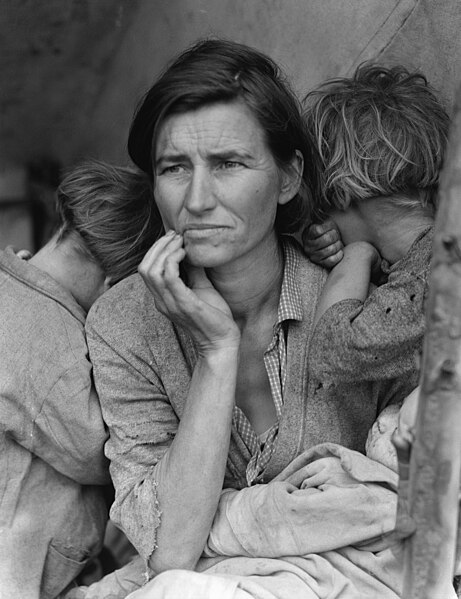

“Poverty” is a word for a very

general concept

Migrant Mother (credit: Dorothea Lange, via Wikimedia Commons)

Early tribes

gradually learned that more general terms – if they accurately described larger

classes of things in reality – could be very useful because more general terms

help us to design more accurately and quickly behaviors that will more often be

effective in our struggle to survive.

Thus, finally, by

this process of greater and greater generalizing, we come to values,

the most general of principles; they apply to large stores of memories of sense

data. We are taught to care about defining a term like good because

we want, ultimately, to survive in greater numbers over the long run. So we are

taught to do the right thing.

Terms for values name

meta-behaviors, programs that are called up and run within our brains. We use

values terms learned from our mentors and teachers to form judgments about what

we are seeing all the time. Values enable us to prioritize and thus, they enable

not just actions, but whole ways of life. They enable us to decide, second by

second, about all we see: important or trivial? Hazard or opportunity? Act or

not? Now? Soon? Later? Ever? How?

Note, also that most

of the time we don’t take any action when an experience is making us think

about one of our values. Often, we recognize a thing is trivial, so we cease to

think about it. Being aware of details in our surroundings does not always mean

we respond to them in any way that shows on the outside. Thinking, even

thinking about our ways of thinking and which of them have been getting good

results lately, is internal behavior. To the frustration of the Behaviorists,

who aim to study only what is objectively observable, what shows outwardly when

we are thinking is often nothing at all.

Modern medical

theory handling reality: vaccination

(credit: Andrew

McGalliard, via Wikimedia Commons)

Some ways of thinking

enhance our chances of finding health and survival. Tribes are always seeking

those ways. Ways of thinking that work effectively over generations are the

ones we keep and teach to our kids. Conversely, people who live by principles

and values that don’t work in reality don’t survive and, thus, don’t have descendants.

In short, values can be understood as proven mental devices for sorting sense

data and responding to events in real life.

Values help us to

organize our sense data and memories of sense data. Over generations, they help

tribe members, individually and jointly, to formulate effective plans of action

in timely ways. In modern terms, we say values "inform" our thinking.

Since reality is always changing, our values must evolve also, though as I said

above, it is sometimes only by the pain of famine, plague, or war that we amend

or re-write our values.

So, let’s now

consider more data/evidence: the ways in which early humans probably formed and

used early examples of principles and values. Let’s test the theory further.

Early hunting tribes,

for example, likely taught their young people methods of killing elk, fish,

birds, etc. and the useful general principles that underlay all of the tribe’s

hunting practices. Crush or sever the spine, right where it enters the skull.

Or pierce the heart. Or cut the throat. Study tracks and droppings. If the

tracks are in new snow, or the droppings are still steaming, the animal is

close by. There were many species to hunt and many ways to stalk and kill each

of them. Over time, the "thought full" tribes that understood and

taught general hunting principles thrived and multiplied.

A hunter needed far

too many behaviors in his repertoire for those behaviors to be learned or

called up one at a time, so hunting principles were invented. In nearly all

cases, hunters found it useful to recall general rules about what they’d seen

and been taught about their target game’s habits. Using these principles, the

hunters would try to anticipate what the animal would do in the upcoming

encounter, on this particular day in this terrain. The hunters would then

prepare psychologically for violent, team-coordinated, physical action. If the

hunt was to be successful, they would need physical and mental preparation.

The exact process by

which each kill would be made could not be known in advance, but the hunters

knew that they would need to act with intelligence (in the planning stage),

then skill and courage (in the doing stage). At the most general level,

successful hunting tribes needed to teach the values that we call courage and wisdom to

their young. These values are so widely applicable in real-life experiences far

beyond hunting that they enable us and our young to deal more effectively with

nearly all of reality. They give us better chances of surviving, reproducing,

and passing the same values on to our children. Again, it is worth noting that

the mechanism of human evolution discussed here is not genetic, but

sociocultural-behavioral, and it assumes conceptual thinking.

Early human art that

shows conceptual thinking

(drawings in Magura cave, Bulgaria) (credit:

Nk, via Wikimedia Commons)

Planting and harvesting grain; ancient

Egyptian hieroglyphs

(credit: Norman de Garis Davies and Nina

Davies, via Wikimedia Commons)

Agricultural

societies succeeded hunter-gatherer ones, and values like patience, foresight,

diligence, and perseverance rose in importance. These values enable and complement

the farming way of life. They didn’t replace hunter-gatherer values totally and

immediately, but the farmers’ values and way of life grew until they, in their

multiplying societies, made old hunters’ values mostly obsolete. The new

agricultural way of life was better at making more humans faster. At that time,

population was a necessary ingredient in armies and power.

Ruins of Ur, ancient

Mesopotamian city

(credit: M. Lubinski, via Wikimedia Commons)

When hard grains that

could be stored indefinitely were domesticated, cities formed. They were

efficient places to store a tribe’s food wealth in a defensible, central site. The

progress from stage to stage had many recursions. Nomadic tribes with little

food and much aggression were lurking. Aggressive nomads might even, for a time,

subjugate and exploit city dwellers. Two ways of life tested themselves against

each other. But in the end, the city dwellers won. They had more, and fitter, food,

goods, weapons, workers, and soldiers.

Inside the new

cities, governing bodies with administrative offices became necessary to ensure

fair distribution of the tribe’s food and to organize the tribe’s members in

ways that brought both domestic order and protection from invaders. Following

them came craftsmen and merchants who found a central, protected site with a

large population more conducive to the practice of their arts than their old

rural settings had been.

A potter

in action at a potter’s wheel

(credit: Yann Forget, via Wikimedia

Commons )

Cities and their ways

proved fitter for economic progress than decentralized farm communities or

nomadic tribes. More citizens working in increasingly specialized skilled tasks

meant more and better goods and services available and thus, over time, helped

to further increase the population.

Values shifted toward

making all citizens content to live in densely populated neighbourhoods,

causing the rise of behaviors that encouraged citizens to respect their

neighbours’ property. Don’t covet the things your neighbor has and don’t bear

false witness against him. The Bible says these things exactly. An ancient book

containing a code by which a real tribe lived in ancient times. Today we can

see why this code worked: envy, especially in crowded towns, raises the odds of

citizens slipping into friction and then violence.

The commandments may

please God; we don't know. But for sure we know these commandments make it

easier for people to live together and get along. Thus, by their commandments,

they increased their tribe’s solidarity, wealth, numbers, and power over the

long haul.

The early city’s laws

expanded the farmer’s guidelines for living in thinly populated farming

communities of familiar faces. These laws prescribed more precisely what kinds

of behaviors were acceptable in nearly all activities of city life. Urban

crowding requires civility. Even the word law came to be

associated with reverent feelings (e.g. for Socrates7).

Most of all, the city

had at its immediate beck and call large numbers who could fight off an enemy

attack. Successful cities even progressed to the point where they could afford

to keep, feed, arm, and train full-time soldiers, professionals who were capable

of outfighting any swarm of amateurs. Farmers remaining in the hinterland moved

closer to the city because life was safer there.

One generation of

life in or near the city taught citizens to be patriotic to their new state.

The cultural programming that successfully reproduced itself made loyalty to

one’s city-state automatic; patriotism is conducive to a city-state’s survival.

In short, patriotism is a program that perpetuates itself. Away from their city

and its morés and values, people came to feel that they could not have a fully

human life. Being fully human meant being Theban or Athenian or whatever was

the term people of a culture used to refer to their hometown.

Ancient Egyptian image of carpenters working

(credit: Maler der Grabkammer

der Bildhauer Nebamun und Ipuki)

(Wikimedia Commons)

Literacy, metals,

machines, factories, and computers all brought values shifts to the nations in

which they first arose. When the ways of life they fostered proved more

vigorous than those of competing societies, the values, morés, and behavior

patterns that rose up with the new technologies were adopted by, or forced on,

those other societies. The values shifts usually also led to revolutions,

nonviolent or violent. Societies that persevered in resisting these shifts in

values and behaviors had to create alternate behavior-generating programs

within their own cultures – programs that were equally effective in the

cultural evolution game – or they got overrun.

Further examples of

morés that illustrate this generalization are easy to find. The fact that so

many of the world’s cultures are patriarchal in design, for instance, is worth pondering.

Female humans appear,

in general, to be marginally less capable than males in some areas such as

large muscle strength and coordination, and in spatial and numerical reasoning

ability.8

But the differences

are small compared with differences among members of the same sex and compared

with the differences between males and females in other species. In addition,

they’re differences that exist between mythical beings called the “average man”

and the “average woman.” Real individuals, male and female, vary considerably

from the mean. Some women are bodybuilders, and some are Math geniuses, while

some men are weak and moronic.

Math genius Emmy Noether

(credit:

unknown photographer, Wikimedia Commons)

Furthermore,

objective, scientific analysis reveals that, on average, females are superior

to males in other ways, such as in coordination of the muscles of the hands and

in verbal reasoning skills. That they have not become the majority of surgeons,

lawyers, and political leaders in most of the world’s societies, jobs for which

they seem better suited, is puzzling to say the least. (Women in the West are

finally achieving parity in medicine, a social change long overdue.9)

Why have females been

relegated to positions of lower status and pay in nearly all the world’s

societies? This seems not only unfair, but illogical and inefficient. Aren’t

such tribes wasting human resources? Unfortunately, logic and fairness have not

been the determining factors. Cultural evolution is subtler, it seems.

Actually, logic and

fairness are just values themselves. In other words, like all values, they’re

tentative. They must serve a society’s survival needs in order to become

entrenched in the value code of that society. If they work counter to the needs

of a society’s survival in vital areas, logic and fairness will be superseded

by what the society will come to call a “higher” value. In the case of women,

for centuries, motherhood was a higher value.

Women bear the young,

and a society’s children are its future in the starkest, most final sense.

Women become pregnant due to anatomy and hormones. We are programmed by our

genetics to find sex pleasurable. We seek it without needing instruction. The

biological drive toward sex is often harnessed and redirected by society’s

programming to serve several of society’s needs at the same time, but these need

not concern us for now. Our line of reasoning has to continue to follow the

developing child – society’s future – in the female womb.

Human females, like almost

all mammalian females, are not as capable of running, hiding, gathering, and

fighting when in advanced pregnancy as when they are not pregnant. After

delivery, the child requires years of nurture before it matures and becomes

able to fend for itself and make adult contributions to society. In short, for

thousands of years, if a society was to survive, its females were needed to

raise kids. Males, in smarter societies, were then programmed into a role which

also supported the nurture of children. It is important to note here that a

male was simply more likely to provide assistance and protection when he

believed that the children were his. These needs led to patriarchal

societies programming women for nurturing and submissive roles. Societies

needed females as willing moms who stayed home and obeyed. First their fathers,

then their husbands.

Individual males who

loved all children were not numerous enough to make a difference to the

long-term odds. Those odds were improved most significantly when most of the

men knew (or thought they knew) which kids were biologically theirs. Let me say

again that this cultural design wasn’t fair. But it was effective. Patriarchy

made population and, thus, it made power.

"Made."

Past tense. Today, in post-industrial society, patriarchy is a cultural design

that has become obsolete. It therefore should be allowed to simply go extinct.

We will discuss this point more in coming chapters.

Note also that male

arousal and orgasm are necessary to procreation; female orgasm is not.

Therefore, societies teaching males to be dominant and females to be submissive

thrived, while competing societies that didn’t teach such values did not. The

logical upshot was that nearly all societies that reproduced at a rate that

enabled them to grow taught their girls to be sexually faithful and generally

submissive to their husbands. Hunter-gatherer societies, agricultural

societies, and industrial societies all grew steadily stronger under patriarchy.

In addition, these

societies evolved toward augmenting their belief in female submissiveness with

supporting values and morés that, in most matters, gave the community’s

approval to male dominance. Other less patriarchal societies stagnated or were assimilated

by expanding, land-seizing, patriarchal ones. Whatever increased male

commitment to child nurture raised the tribe’s odds of going on. Again, note

that the history of these societies was often not shaped by a gender-neutral

concept of justice. Justice bowed to nurture. Survival.

In today’s

post-industrial societies with computer technologies (and the changes they have

brought to our concepts of work and home), women can now contribute children

and work other than child nurturing to all areas of their culture’s ongoing

development and life. The imperatives of the past that dictated girls had to

adopt submissive roles to ensure the survival of their tribe and its culture

are evolutionarily obsolete. Advances in birth control technology (e.g. oral

contraceptives) and in child-rearing and nurturing technology (e.g., artificial

insemination, infant-feeding mixtures) have made the chores and joys of child-rearing

possible for men, and for single women, who in earlier eras had little choice

but to forego the joys and trials of parenting or suffer, in themselves and through

their children, cruel social stigma. “Bastard” is an ugly word.

Dad

with infant daughter (credit: Kiefer Wolfowitz, Wikimedia Commons)

In post-industrial

societies, there is no survival-oriented reason for women not having as large

and varied a range of career and lifestyle choices as those open previously

only to men. There is no survival-driven reason for any person not receiving

pay commensurate with the open market value of her/his contribution to the

nation’s ongoing life and development.

Computer programmer

(credit: Joonspoon, via Wikimedia Commons)

In fact, what appears

to be true is that any limitations placed unduly or unequally on the

opportunities of any citizens in the community on the basis of gender, sexual

orientation, or race are only reducing the community’s capacity to grow and

flourish. Computer technology and the oral contraceptive have made a higher

degree of gender-neutral justice possible. If we wish to maximize our human

resources, become as dynamic a society as possible, and compete ever more successfully

in the environments of our planet and perhaps beyond, we must make education

and careers of the highest quality open to all citizens. If we are to maximize

our human resources, then access to education and careers should be based on

merit alone. At least, such is the conclusion we must draw from the reasoning

and evidence we have before us today.

Furthermore, the

authorities of society, if only for efficiency’s sake, probably will have to

find ways of ensuring that quality nurturing of children receives pay and

benefits matching the pay and benefits given to other similar jobs in a society

traditionally driven by these incentives. Having kids will have to be a

reasonable option if we are to maintain a stable base population for our

society in this new century.

Driving women back

into the domestic zone would be counterproductive, like locking our bulldozers

in sheds and digging ditches by hand in order to create jobs. For women and men

who choose it, nurturing children must be given real respect and pay if we are

to continue on the path of knowledge-driven evolution that we have evolved into

and that has now become our way of life.

Whether this

expanding of gender roles and child-rearing practices will endure is still

unclear. Will women be, finally, equal partners with men? Moves toward gender

equity, in work and citizenship, and real change in the everyday life

experiences of women and men, have been tried (to varying degrees) before. And

have faded away before. But the trends in the West, especially at the start of

the twenty-first century, look widespread and strong. The question will be

whether societies that contain a higher degree of gender equity will outperform

those that do not. The answer will emerge gradually over the next century.

This digression on

the sociocultural model of human evolution and examples of familiar morés that

we can imagine being revised is intended to emphasize the fact that our morés

and values are programmable. We can rewrite them by rational discussion and

processes that are based on reasoning, evidence, and compromise. Then, we

put them in the schools in which we instruct our young. For the betterment of

the whole of human society, we can remake us. Difficult, but infinitely

preferable to the blind, inefficient, painful mode of social change that we

have been using for centuries.

It is time for reason

to take over. The hazards of continuing the old ways of prejudice, revolution,

and war are too large. We have to find another way, one that rights gender,

racial, and class injustices without resorting to the horror of war. The goal

of this book is to show that we can find a new way to design our values, a moral

code and way of life founded on our best models of physical reality and the

evidence for those models that lies in experience itself. Then, a

transformation of the nations of the world into one nation will come.

Now let’s return to

our main argument, in spite of digressions that beckon.

Human behaviors and

values almost all originate in the programming put into each individual by his

or her society. In addition, values become established in a society when they

direct that society’s citizens toward patterns of behavior that enable the

citizens to survive, reproduce, and spread in the real world.

It is also worth

noting here that individuals can cause changes to their societies. Changes in

beliefs and customs do not come only from inscrutable processes not accessible

to human detection or analysis. We can see what needs to change and, sometimes,

change it. For most of us, the changes we can bring about are small, but for a Newton,

a Gandhi, or a Martin L. King, those changes can be considerable. But we can

change, we can do it by non-violent means, and brave individuals can be the key

causative agents of that change. There is hope.

We are now able to conclude

this chapter with a major insight into cultural evolution, what it is and how

it works. After looking over many examples of human beliefs and the customs

they foster, we can conclude that the deepest, most general principles that should

guide how we build our values – in big choices for the tribe and small ones for

individuals – should be the most general principles we can spot in the world around us. These are simply the principles underlying our existence, the principles of the universe itself.

If we want to

survive, avoid pain, and enjoy life, first, we have to understand the principles

of the place – this universe – in which we want to do those things.

So, what principles

of reality are relevant to how we build our moral codes? For impatient readers,

I can only say I am coming to them – by small steps and gradual degrees. But we

have to thoroughly discuss the network of ideas at the base of the new moral

system before we try to build the middle and upper levels.

Epistemology first,

then Ontology, then Methodology, then Moral Philosophy.

My proceeding with

care will maximize the chances of my readers seeing that a universal moral code

is possible for us to devise, and that this code of decency and sense, if we

can implement it, offers the only path into the future by which we may survive.

Logically, at this point then, I should discuss more societies of the past,

their worldviews, and how their worldviews shaped their ways of life.

But first, I must

digress for a while. A sad but necessary digression.

Notes

1. http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20151012-feral-the-children-raised-by-wolves.

2. “Enculturation,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed April 20, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enculturation.

3. “Sociocultural evolution,” Wikipedia, the

Free Encyclopedia. Accessed April 20, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sociocultural_evolution#Contemporary_discourse_about_sociocultural_evolution.

4. Pearson Higher

Education, “Anthropology and the Study of Culture”

Chapter 1, p. 17.

http://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/hip/us/hip_us_pearsonhighered/samplechapter/0205949509.pdf.

5. Alice Dreger,

“When Taking Multiple Husbands Makes Sense,” The Atlantic, February

1, 2013.

http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/02/when-taking-multiple-husbands-makes-sense/272726/.

6. “Piaget’s theory

of cognitive development,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Accessed April 20, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piaget’s_theory_of_cognitive_development.

7. Plato, Crito,

Perseus Digital Library. Accessed April 20, 2015.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0170%3Atext%3DCrito%3Apage%3D50

8. Mark J. Perry,

“U.S. Male-Female SAT Math Scores: What Accounts for the Gap?” Encyclopedia

Britannica blog, July 1, 2009.

http://www.britannica.com/blogs/2009/07/more-on-the-male-female-sat-math-test-gap/

9. Jenny Hope, “Women

Doctors Will Soon Outnumber Men after Numbers in Medical School Go up

Tenfold,” Daily Mail online, November 30, 2011. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2067887/Women-doctors-soon-outnumber-men-numbers-medical-school-fold.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.