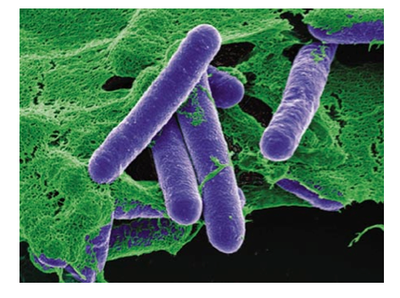

Clostridium Botulinum

Another

more general example of the dangers posed by an inaccurate picture of reality

lies in the common activity of home canning. I may think I know all about

bacteria and how to can foods at home in sealer jars. If I’ve looked through

microscopes, I may be confident my picture of the microscopic level of reality

is a true one. But if my knowledge of home canning covers only common bacteria,

my limited knowledge may prove to be a dangerous thing. The usual boiling-water

bath for foods canned in jars does kill most bacteria, but for a few microbes,

boiling is not enough. Botulism is nothing to be played around with. Botulinum

bacteria can be boiled to death, but their deadly toxins can survive boiling.

My partial and inadequate set of beliefs about home canning might get me

killed.

Or

consider a few even more basic examples. Even my senses sometimes are not to be

trusted. I may believe that light always travels in straight lines. I may see,

half immersed in a stream, a stick that looks bent at the water line, so I

believe it to be bent. But when I pull it out, I find that it is straight. If I

am a caveman trying to spear fish in a stream, blind adherence to my ideas

about light will cause me to starve. I will overshoot the fish every time,

while the girl on the other shore, a better learner, cooks her catch.

I

can immerse one hand in the snow and keep the other on a hand warmer in my coat

pocket. If I then go into a cabin to wash my hands in tepid water, I find that

one hand senses the water is cold, the other, that it is warm. Can I not trust

my own senses?

When

we seek to find some things in our experience that we can believe in

absolutely, we are stopped by questions like “What do I really know?” and “How

can I be sure of the things that I think I know?” and “Can I even be certain of

what I see, hear, and touch?” We

are deeply aware that we need a reliable core around which we can build the

rest of our belief system or we may, sometime down the road, suddenly find that

a whole set of ideas, and the ways of living the system implies, are dangerous

illusions.

Even

a complete world view, learned, used, and trusted, may turn out to be a fraud.

Nazism may sound logical if I am told as a boy, by teachers I trust, that every

race on earth including my own must fight to survive. I may come to truly

believe in their model of the workings of our planet’s biosphere. If I believe

it, I may then infer that winning new land for my race and subjugating

competing races is my sacred duty to my people. I and millions of like-minded

comrades may march off to a war that gets millions killed before my nation

loses and the war is finally over.

World War II cemetery for German dead, Ysselsteyne, Holland

The

problem was that the Nazi worldview was built around a core set of lies. The

Nazi ideas of race have no foundation in fact; humanity is one species. In science,

there is no Aryan race. Different nations and cultures do compete and struggle

to survive, and Germany was, and is, a nation that has had one of the harder

struggles. But culture is not genetically acquired. Culture is learned;

therefore, cultures can be amended by education and experience. In addition, war

is not the only way by which cultures can evolve. Germany, as a nation, changed

profoundly after WWII, but then it continued on—very successfully, in fact. It

didn’t fizzle out and vanish as Nazi leaders had predicted it would if it lost

the war. Millions of Germans and their adversaries died because of an illusion.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.