Chapter 11 – Historical World Views

Every

society must work out and articulate a view of the physical universe, a way of

seeing the world, a way that then becomes the base on which the society’s value

system is to be built. This is no minor matter; while philosophers may dally

over the questions in a theoretical way, real folk have to deal with life. They

have to have some code in place that helps them decide them how to act. World

view, values, and behaviours must form a coherent system under which each

individual is empowered to make decisions and take action so the entire society

can efficiently operate and survive in its always changing, always demanding

environment.

All

societies know this in some deep way. Societies up until our time have worked

out their world views, values, and morés to the extent they have because people

everywhere have always placed great stock in their society’s model of how the

material universe is constructed, how it operates, and where it is going. They

know implicitly that their worldview must be used as their guide when they are

trying to decide whether an act that feels morally right is practicable. There

is no point in striving for the impossible.

So

let’s keep moving forward in this task of building a new, universal moral code,

but let’s also move with all the prudence we possess. What is at stake is

everything. Before we begin building this new system, we need to get our

thinking into the necessary mindset by considering the most salient peaks in

the histories of some of the societies of the past, in order to see how systems

of world views, values, and behaviors coordinate and evolve.

G.W.F. Hegel

In

this chapter, philosophy students will notice similarities between some aspects

of my ideas and the philosophy of Hegel, and I admit freely that similarities

exist. But I also have some major points of disagreement with Hegel, which I

will explain along the way. For those readers who are not philosophy students, please

note that I will give only a very quick version of my understanding of Hegel.

If you find the ideas presented here at all interesting, you really should give

Hegel a try. His writing is difficult, but not impossible, and it has also been

interpreted by some disciples who write more accessibly.1 But in

this book, let’s now get back to our analysis of the world views, values, morés,

and behavior patterns that are discernible in the history of some of the

societies of the West.

BBC film director’s conception of

Trojans dragging wooden horse into Troy

For instance,

let’s consider the ancient Greeks, the ones who came long before Socrates’

time. They portrayed the universe as an irrational, dangerous place. To them,

the gods who ran the universe were capricious, violent, and cruel, which also

described the Greeks’ world view. Under this view, humans could only cringe

fearfully when confronted with the gods’ testy humors. Zeus, Hera, Poseidon,

Ares, Hades, Athena, Apollo, and the rest were all lustful, jealous, cruel, and

unpredictable. Zeus, especially, had thunderbolts; Poseidon inflicted

earthquakes; Apollo, plagues.

But

as Greek culture advanced, this worldview evolved. By the Periclean Age, many

Greek stories and plays portrayed humans challenging the gods. At the same

time, the Greeks evolved their system of values toward a braver, smarter

lifestyle. They began trying to explain the world in ways that left room for

people to understand and manipulate at least some of the events in their world.

Once their worldview included those possibilities, they began to create action

plans that enabled humans to cause, hasten, or forestall events in the world.

They tried out the daring plans; when some worked, more daring plans

followed. (Edith Hamilton articulates these ideas well.2)

Aristophanes, Greek

comic playwright

It

is important to see that human individuals and groups will normally not attempt

any action they consider taboo. Ancient tribes who happened upon an action that

seemed contrary to or outside of what was appropriate for humans in their worldview

only grew upset and fearful. Whether the action obtained promising results or

not, the only thing most of those people wanted to learn was how to avoid

putting themselves in the same situation again. They sought to avoid it for

fear of bringing the gods’ wrath down on them. Once in a long while, a genius

might question his society’s worldview and even describe an alternative one,

but he often paid dearly for such audacity—by being ostracized or put to death.

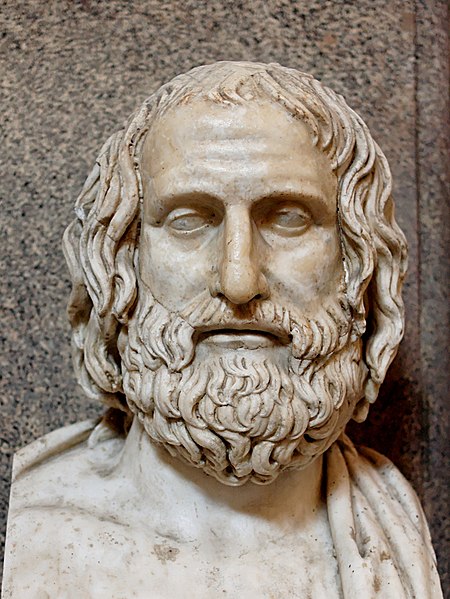

Euripides, Greek tragic

playwright

However,

changes in a society’s worldview and then in the society’s values and morés can

also evolve more gradually, helped by many lesser geniuses. By the Golden Age

of Athens, writers, artists, and philosophers were attempting all kinds of

things that only a few centuries earlier would have been unthinkable. Their worldview

had evolved to allow for at least some degree of human free will. The works of

Euclid, Plato, Euripedes, Archimedes, and Aristotle could only have been

produced under a worldview in which a person could conceive of actions

challenging the orthodox beliefs of the tribe and even the forces of the

universe, even though the challenge might rarely succeed. At the same time, their

neighbours, the Spartans, were evolving their destructive society, the perfect

military state. The clash called the Peloponnesian War was inevitable, and

Athens lost. A few years later, the Macedonians out-Spartanned the Spartans,

and after another generation or two, the Romans ended the matter by conquering

them all.

Artist’s conception

of a Roman warrior

Thus in Western

history, the next important worldview is the Roman one. Operating under it,

people became even more practical, more focused on physical effectiveness and power,

and less interested in or even aware of ideas considered for their own sake. Among

many of the early Romans, this feeling expressed itself in a hatred of all things

Greek; the truth was that the Romans borrowed much from the Greeks, especially

in theoretical knowledge, but they loathed having to admit it.

In their heyday, the

Romans no longer feared the gods in the way the ancient Greeks and the Romans’

own ancestors once had. As the republic faded and the empire took over, the

Romans turned so far from earlier thinking that they lost much of the Greek,

especially the Athenian, capacity for abstract things—wonder, idealism, pure geometry,

philosophical speculation, and flights of imagination. The Romans built their

state on Athenian-style, democratic principles, values, and behaviors, but

like the Spartans, they loved results and power, not speculation.

Pont du Gard: Roman

aqueduct in present-day France

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.