Chapter 1 – Science Gets the Blame

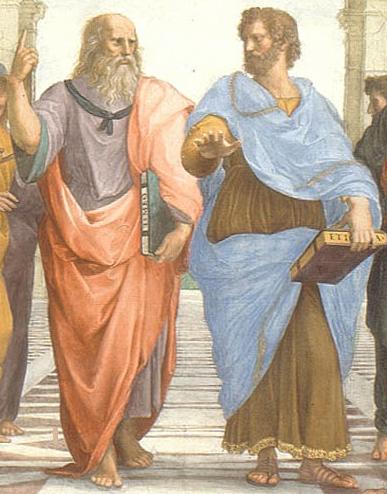

Plato (l) and Aristotle (r). The School of Athens (Raphael) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Science

gets the blame—or the credit, depending on your point of view—for having eroded

the base out from under the moral systems that our ancestors lived by and

depended on. For the most part, it fully deserves this blame. Prior to the

scientific revolution, people were pretty miserable in terms of their physical

lives. Life was hard for nearly all folk and death came soon. Famines, plagues,

and war swept the land. Infant mortality rates are estimated to have been between

30 and 50 percent 1, and life expectancy was under forty years.2

But

people knew where they stood in society, and they knew where they stood—or at

least should be trying to stand—in moral terms, in their relationships with

other people, from the bottom of society to the top. Kings had their duties

just as noblemen, serfs, and craftsmen did, and all of their wives did, and

sins had consequences. God was in his heaven; he enforced his rules—harshly but

fairly, even if humans couldn’t always see his logic and even if his justice

sometimes took generations to arrive. People knew “what goes around comes

around.” For most folk, all was right with the world.

.jpg/821px-Francis_Bacon,_Viscount_St_Alban_from_NPG_(2).jpg)

Francis Bacon (Vanderbank) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The

scientific revolution essentially began from a new method for studying the

physical world, a method proposed most articulately by the English Renaissance philosopher,

Francis Bacon. For centuries before the Renaissance, most people who studied

the material world had followed the models of reality that had been laid down

in the texts of the ancient Greeks, or even better, in the Bible. Works by

Aristotle, in particular, described how the natural world worked in almost

every one of its aspects, from atomic theory to biology to cosmology.

On

most matters, the Greeks were seen as having merely described in more detail

what had been created in the first place by God, as the Bible plainly showed.

In most fields, original thought was not resented or despised. It was simply

absent. Thus, for over a thousand years, our forbearers believed the classic

Greek works and the Bible, when taken together, contained every kind of wisdom

(from ancient Roman times to the Renaissance) that human beings could want to

know. A true gentleman’s life duty was to pass on to his sons, intact, the

beliefs, morés, and values of his ancestors.

Thomas Aquinas (credit: Wikipedia)

Was

there any danger that the ancient Greek texts and the Bible might

irreconcilably contradict each other? No. Several experts, including Thomas Aquinas,

had shown that these two sources were compatible with each other. Even if

inconsistencies were found, of course, the divine authority of the Bible

resolved them. For the folk of the West, for centuries, the Bible was the word

of God. Period. It had to be obeyed.

In

every field, if you wanted to learn about a subject, you consulted the

authorities—your priest or the teachers who taught the wisdom of the sages of

old. But for most folk, deeply analyzing events in their own lives or analyzing

things the authorities told them wasn’t so much worrying as inconceivable. Over

90 percent of the people were illiterate. They took on faith what the

authorities told them because everyone they knew had always done so. A mind

capable of memorization and imitation was valued; a questioning, innovative one

was not.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.