First, then, what are the values that enable humans

to respond to the main consequence of entropy, the unceasing, uphill struggle

of life, the quality of life we know as adversity?

A whole array of values should be taught to young

people to enable them to deal with adversity. In order to deal well with

adversity, a society needs large numbers of people willing, even eager, to face

constant struggle, exertion, exhaustion, and pain. In fact, a society proves

most effective and durable if its citizens take up the offensive against the

relentless decay of the universe. Children taught to embrace challenge become

adults who seek to bring new territories (perhaps even planets) under their

tribe’s control, to devise new ways of growing and storing food and building

shelters, to use technology to accomplish more work with less human exertion, and,

in general, to perform the tasks of survival more efficiently.

When we generalize about what these entropy-driven

behaviour clusters have in common, we derive two giant values that are found in

all cultures; these are courage and wisdom.

In different cultures all over the world, courage

is instilled in the young, which is what we would expect if it really does

work. Bergson spoke of élan,

Nietzsche of the will to power.1

Japanese samurai women and men lived by bushido,

their code of total discipline, and European nations lived by a similar code, chivalry, right into modern times. But

beyond the difficulties of translation from culture to culture and era to era,

we see in all these values a common motif: they all direct their disciples to

train themselves to persevere through challenges and obstacles of all kinds,

even to seek challenge out. Achilles chose a brief, hard life of

honour over a longer, easier one of obscurity. For centuries, the ancient

Greeks considered him to be a model of a man, as do some people in nations that

have absorbed ancient Greek culture to this day. Many other cultures have

similar heroes.

The Triumph of Achilles (Franz Matsch, artist) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

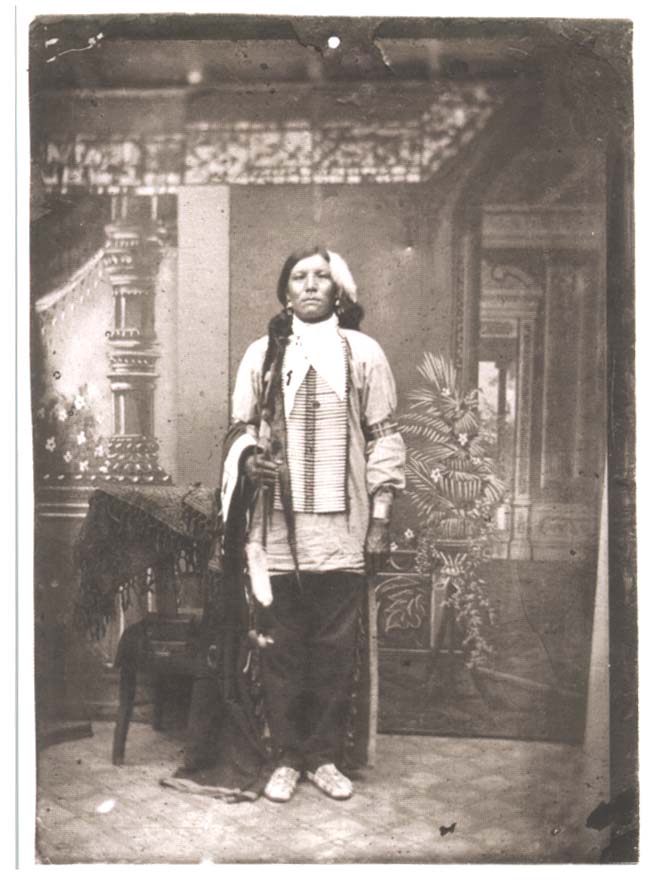

Alleged photo of Apache

leader Crazy Horse, c. 1877 (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Zulu leader, Shaka (statue in London, England) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Martial arts master and Chinese hero, Huo Yuanjia (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Confucius said that the superior man thinks always

of virtue, while the common man thinks always of comfort. Nineteenth-century

English writer K.H. Digby put it this way: “Chivalry is only a name for that

general spirit or state of mind which disposes men to heroic actions, and keeps

them conversant with all that is beautiful and sublime in the intellectual and

moral world.”2

The exhortation to meet and even seek adversity

echoes through all societies. Young people everywhere are especially encouraged

to face hazards in defense of their nations. We can sum up the gist of all of

these values by saying that they are built around the principle that in English

is called courage.

It is familiar and clichéd to push young people to

aspire to courage. But clichés get to be clichés because they express something

true. In the hazardous background of the physical universe, life strives to

create stable, growing pockets of order. In the case of humans, it does so by programming

into young people an entire constellation of values and mores around the prime value

called “courage”. From it, behaviors that meet and overcome adversity flow, and

societies that believe in courage survive better because of that belief.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.