Chapter 6 Rationalism and Its Flaws

In Western

philosophy, Rationalism is the main alternative to Empiricism

for describing the mind and for modeling what knowing is. It is the way of

Plato in Classical Greek times and of Descartes in the Enlightenment.

Rationalism claims

that the human mind can build a system for understanding itself and for how it “knows”

its world only if that system is first of all grounded in the human mind by

itself, before any sensory experiences or memories of them enter the

thinking system. You can know unshakable truth by beginning inside of your own

mind. In fact, that is the only reliable way to know truth.

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Descartes, for

example, points out that our senses give us information that can easily be

faulty. As was noted above, the stick in the pond looks bent at the water line,

but if we remove it, we see it is straight. The hand on the pocket warmer and

the hand in the snow can both be immersed shortly after in tepid tap water; to

one hand, the tap water is cold and to the other, it is warm. And these are the

simple examples. Life contains many much more difficult ones.

Therefore, the

rationalists say, if we want to think about thinking in rigorously logical

ways, we must try to construct a system for modelling human thinking by

beginning from some concepts that are built into the mind itself before any

unreliable sense data or memories of sense data even enter the picture.

Plato says we come

into the world at birth already dimly knowing some perfect forms that we

then use to organize our thoughts. He drew the conclusion that these useful

forms, which enable us to make sense of our world, are imperfect copies of the

perfect forms that exist in a perfect dimension of pure thought, before birth,

beyond matter, space, and time – a dimension of pure ideas. The material world

and the things in it are only poor copies of pure forms ultimately derived from

the pure Good. The whole point of our existence, for Plato, is to discipline

the mind by study until we learn to clearly recall, understand, and live by,

the perfect forms – perfect tools, perfect medicine, perfect beauty, perfect

animals, perfect courage, perfect love, perfect justice, and so on.

Descartes formulated

a similar system of thought that begins from the truth the mind finds inside

itself when it carefully and quietly contemplates just itself. During this

quiet and totally concentrated self-contemplation, the thing that is most

deeply you, namely your mind, realizes that whatever else you may be mistaken

about, you can’t be mistaken about the fact that you exist; you must exist

in some way in some dimension in order for you to be thinking about whether you

exist. For Descartes, this was a starting point that enabled him to build a

whole system of thinking and knowing that sets up two realms: a realm of things

the mind deals with through the physical body attached to it, and another realm

the mind deals with by pure thinking, a realm built on the clear and

distinct ideas (“clarus et distinctus essentiam”) that the mind knows

before it ever takes in any impressions coming from the physical senses.

The science of

Psychology has cast a harsh spotlight on the inconsistencies of Rationalism. As

was shown in our last chapter, the moral philosophers’ hope of finding a foundation

for a moral system in Empiricism was broken by Quine and Gödel and other

thinkers like them. Rationalism’s flaws have been just as clearly exposed by

psychologists such as Elliot Aronson and Leon Festinger.

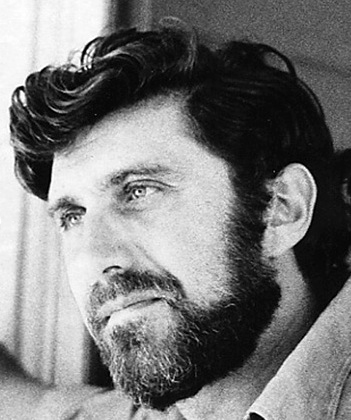

Elliot

Aronson (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Aronson was

Festinger’s student. He went on to win much acclaim in his own right. They both

focused their work on cognitive dissonance theory, which describes a human

mental habit. The theory is fairly easy to understand, but its consequences are

profound and far-reaching. Basically, the theory says that the inclination of

the human mind is always toward finding good reasons to justify what we want to

do anyway, and even more firmly believed reasons to justify the things we’ve

already done. (See Aronson’s The Social Animal.1)

What it says essentially

is this: a human being tends, actively, insistently, and insidiously, to think in

ways that affirm itself. In every action the mind directs the body to perform,

and in every phrase it directs the body to utter, it shows a desire to remain

consistent with itself. In practice, this means all humans tend to find and

state good reasons for maintaining the way of life in which they have become

comfortable. Or at least the reasons sound good to them. Every human mind

constantly strives to make theory match practice or practice match theory – or

to adjust both – in order to reduce any internal feelings of discomfort. (“Am I

being a hypocrite here?”, we ask ourselves.) This kind of feeling of internal

discomfort is what psychologists call cognitive dissonance.

A novice financial

advisor who used to speak disparagingly of all sales jobs will soon be able to

tell you with heartfelt sincerity why every person, including you, ought to

have a carefully selected portfolio of stocks. A physician adds another bank of

expensive therapies – of doubtful effectiveness – every year or so to his

repertoire. The plastic surgeon can show with argument and evidence that the

cosmetic procedures he performs should be covered by the state’s health-care

plans because his patients aren’t vain, they are “aesthetically

handicapped.”

The divorce lawyers

are not setting two people who used to love each other at each other’s throats.

They are merely defending their clients’ interests, while the clients’ misery

grows worse every week. The cigarette company executive not only finds what he

truly believes are flaws in cancer research, he smokes over two packs a day.

The general sends his own son to the front. And his mother-in-law’s decent

qualities (not her crude ones) become more obvious to him on the day he learns

that she owns over ten million dollars’ worth of real estate. (All that landlord-stress!

No wonder she’s sometimes crude.)

And what of the

Philosophy professor, whose mind is trained to seek out inconsistencies? He

once said he believed in the primacy of the rights of the individual over any

group’s rights. He sought to abolish any taxes that might be used to pay for

social services. Private charities could do such work, if it needed to be done

at all. But then his daughter – who suffers from bipolar disorder and who

sometimes secretly goes off her medications and runs away from all forms of

care, no matter how loving – runs off and becomes one of the mentally ill homeless

in the streets of a distant city. She is spotted and saved by alert street

workers, paid (meagrely) by the state. Now he argues citizens should pay taxes

that can be used to hire street workers who look out for the destitute.

In addition, he once

considered euthanasia to be totally immoral. But now his aging father who has

Alzheimer’s disease has been deteriorating for over five years. Professor X is

broke, sick, and exhausted. He longs for the heartache to be over. He knows

that he cannot keep caring, day in and day out, for the needs of this now

unrecognizable, pathetic, gnarled creature for very much longer. Even Dad, the

dad he once knew, would have agreed. Dad needs and deserves a gentle needle.

Professor X is certain of it, and he tells his grad students and colleagues so

during their quiet, confidential moments.

The two most famous rationalists

have had millions of followers – in Descartes’s case for four hundred years and

in Plato’s case for well over two thousand. They have attacked empiricism for

as long as it has been around (since the 1700s, or in a simpler form, some

argue, since the time of Aristotle, who was Plato’s pupil, but who disagreed

diametrically with Plato on many matters).

The debate between

the rationalists and the empiricists has not let up, even in our time. But in

our quest to find a universal moral code, we will find that we must discard

rationalism just as we did empiricism; rationalism contains a flaw worse than

any of empiricism’s flaws.

Eohippus (artist's conception)

(By

Heinrich Harder [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Do we, in our endlessly

subtle rationalizations, see what is not there? Not really. A fairer way of

describing this dissonance-reducing tendency in human minds is to say that out

of the billions of sense details, the googols of patterns we might see among

them, and the infinite interpretations we might give to those details, we tend

to give primacy to those that are consistent with the view of ourselves we find

most comforting. We don’t like seeing ourselves as hypocrites. We don’t like

nagging feelings of cognitive dissonance. Therefore, we tend to be drawn to

ways of thinking, speaking, and acting that reduce that dissonance, especially

in our internal pictures of ourselves. In short, we need to like ourselves.

There is nothing

really profound being stated so far. But when we come to applying this theory

to philosophies, the implications are a little startling.

Other than

rationalizations, the rationalists have nothing to offer.

What are Plato’s forms?

Can I measure one? Weigh it? If I claim to know the forms and you claim to know

them, how might we figure out whether the forms you know are the same ones I

know? If, in a perfect dimension somewhere, there is a form of a perfect horse,

then what were the beasts called eohippus and mesohippus (biological

ancestors of the horse), who were horsing around long before anything Plato would

have called a “horse” existed?

Questions similar to the ones we can ask about Plato's rationalism, can be asked about Descartes' version: What are Descartes' clear and distinct ideas? Clear and distinct to whom? Him? His contemporaries? To me, they do not seem so clear and distinct that I can stake my thinking – and thus my sanity and survival – on them. Many people don’t know and have never known what he’s talking about. Not in any language. Yet they’re fully human people. Descartes’ favourite clear and distinct ideas – the basic ideas of arithmetic and geometry – are unknown in some human cultures.

This evidence suggests

strongly that Descartes’ categories are simply not that clear and distinct. If

they were inherent in all human minds, all humans would contain these ideas from

birth – which they clearly don’t. (A point first noted by Locke.) Looking at a

broad spectrum of humans, especially those in other cultures, tells us that

Descartes’s clear and distinct ideas are not built in. We acquire them by

learning them from other humans. Arguing that they are somehow real, and that

in the meantime sensory experience is illusory, is a way of thinking that can

then be extended to arguing for the realness of the creations of fantasy

writers. In The Hobbit, Tolkien describes Ents and Orcs. I go along

with the fantasy for as long as it amuses me. But there are no Ents, however

much I may enjoy imagining them.

In short, by a little

reasoning, we can see that Rationalism undermines itself.

J.R.R.

Tolkien (1916) (credit: Wikipedia)

So, then what are

our concepts?

They are mental

models that we devise to help us to organize our memories. Our memories are

what we consult as we go through the world and try to act effectively. We

invent concepts by looking over our memories to find patterns. When we

see a pattern, we put a concept-label on that file of memories. The concept

helps us to sort through memories more reliably and quickly so that we can make

effective plans and act on them in timely ways. We try the concept out, i.e. we

use it to make plans and then we enact those plans. If a concept helps us to

get good results, we keep it. When it doesn't seem to work well anymore, we

nearly always drop it and look around for a newer, better tool.

Even ideas of

numbers, Descartes’s favourite “clear and distinct” ideas, are just mental

tools that are more useful than ideas of Ents. Counting things helps us to act

strategically in the material world and thus to survive. Imagining Ents gives

us temporary amusement – not a bad thing, but not nearly as useful as an

understanding of numbers.

But numbers, like

Ents, are mental constructs. In reality, there are never two of anything. No

two people are exactly alike, nor are two trees, two rocks, two rivers, or two

stars. So what are we really counting? We are counting clumps of sense data

that roughly match concepts built up from memories, concepts that were built on

much larger banks of data, and that have been tested and proven to be far more

useful for survival than the concept of an Ent.

Even those concepts

that seem to be built into us (e.g. basic language concepts) became built-in

because, over eons of evolution of our species, those concepts gave a survival

advantage to their carriers. Language enables better teamwork; teamwork helps a

human tribe to get things done. Thus, language is a physically explainable

phenomenon. It belongs in the fold of empiricism.

Geneticists can

locate the genes that enable a developing embryo to build a language centre in

the future child’s brain. Later, an MRI scan can find the place in your brain

where your language program is located. If you have a tumor there, a neurosurgeon

may fix the “hardware” so that a speech therapist can help you to fix the

program. In other words, the surgery on a physical part of you can give you

back your ability to speak. Even the human capacity for language is an

empirical phenomenon all the way.2

Stone

Age (artist: V. Vasnetsov)

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

In the meantime, eons ago, counting enabled more effective hunter behavior. If a tribe leader saw eight of the things his tribe called deer go into the bush and if he counted only seven that came out, he could calculate that if his friends caught up, circled around in time, and executed well, and if they worked as a team and killed the deer, this week the children would not starve. Both the ability to count things and the ability to articulate detailed instructions to the rest of one’s tribe boosted an early tribe’s survival odds. That’s why numbers and words were invented and used and are still being used. They work.

The basic concepts of

math and language got built up in us because those who had them and used them

survived in greater numbers than those who didn't.

If the precursors of

language seem to be genetically built into us (e.g. human toddlers all over the

world grasp that nouns are different from verbs) while the precursors of math

are not, this fact only shows that basic language concepts proved far more

valuable in the survival game than basic math ones. (Really useful concepts,

like our wariness of heights or snakes, got written into our genotype long

before language arrived.) The innate nature of language skills, along with the

usefulness of language, indicates that basic language concepts do not come to

us by any mysterious, inexplicable process out of an ideal dimension of the

Good. All these human traits have material explanations.

We do not have to

believe – as the rationalists say we do – in another dimension of pure thought,

with herds of “forms” or “distinct ideas” roaming its plains, in order to have

confidence in our own ability to reason. By nature, or nurture, or subtle

combinations of the two, we acquire and then pass on to our children those

concepts that enable their carriers – i.e. the next generation of humans – to

survive. In short, our ability to reason can be explained in ways that don’t

assume any of the things that Rationalism assumes.

And now Rationalism’s

disturbing implications start to occur to us. Wouldn’t I love to believe that

there is some hidden dimension in which the forms exist, perfect and eternal?

Of course, I would. Then I would know that I was “right.” Then I and a few

simpatico acquaintances might agree among ourselves that we were the only

people truly capable of perceiving the finer things in life or of recognizing

which are the truly moral acts. Our training and natural gifts would have

sensitized us to be able to detect the beautiful and the good. For us to

persuade the ignorant masses – by whatever means necessary – would only be rational.

Considering their inability to figure things out for themselves, it would be an

act of mercy for us to get control of the nation and keep it.

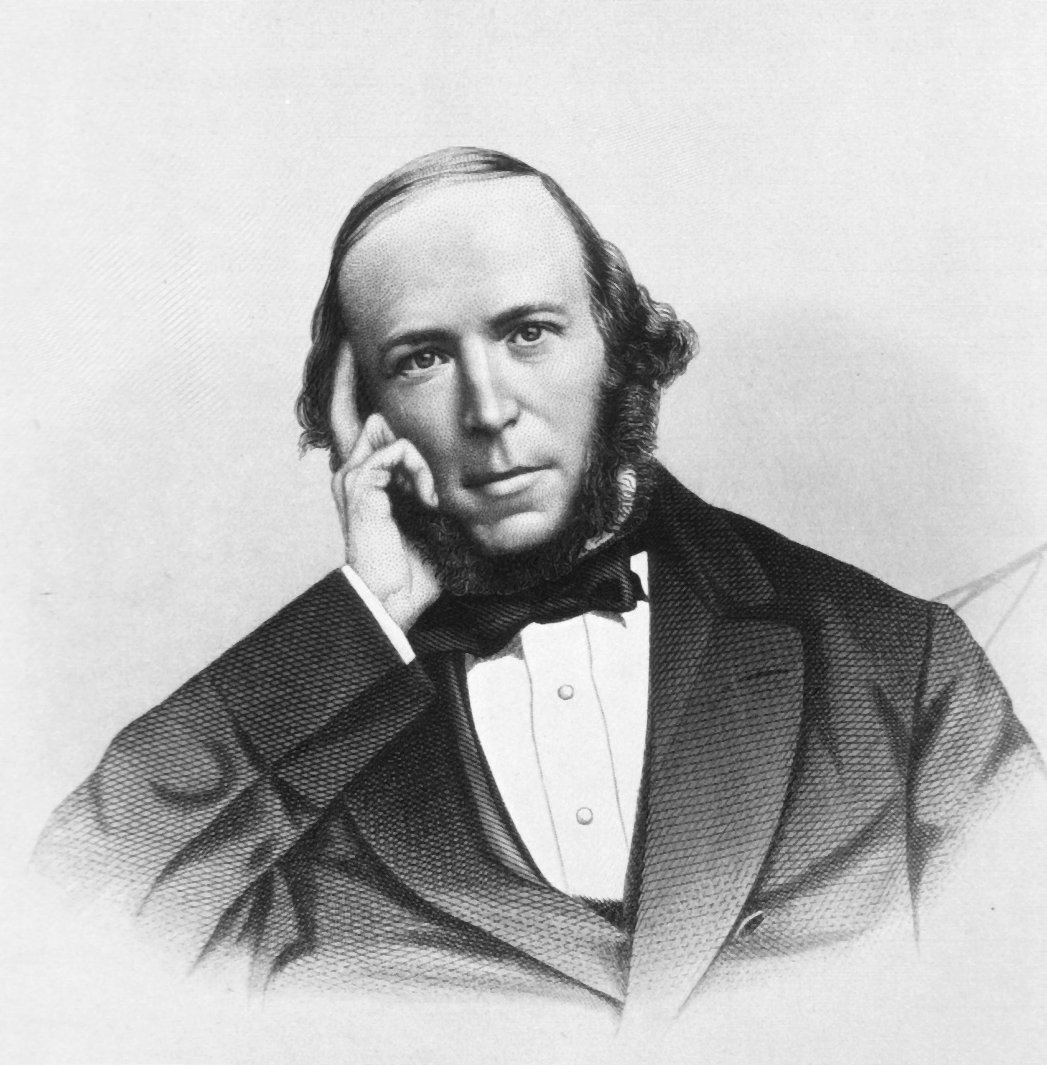

This view is not just

theoretically possible. It was the view of some of the disciples of G.E. Moore

almost a century ago and, even more blatantly, of some of the followers of

Herbert Spencer a generation before that. (Explanations of the views of Moore

and Spencer can be found in Wikipedia articles online.3,4)

Herbert Spencer (credit Wikimedia Commons)

I am being sarcastic

about the sensitivity of Moore and Spencer’s followers, of course. Both my

studies and my experience of the world tell me there are more than a few of

these kinds of sensitive aristocrats roving around in today’s world, in every

land (the neocons of the West?). We underestimate them at our peril. The worst

among them don’t like democracy. They yearn to be in charge, they have the

brains to secure positions of authority, and they have the capacity for

lifelong fixation on a single goal. Further, they have the ability to

rationalize their way into truly believing that harsh, duplicitous measures are

sometimes needed to keep order among the ignorant masses – that is, everyone

else.

Out of our discussion

of Rationalism, the conclusion to draw is that too often it is a close

companion of totalitarianism. The reason does not become clear until we

understand cognitive dissonance. Understanding how cognitive dissonance works

enables us to see how inclined toward rationalization other people are and how

easily, even insidiously, they give in to it. On what grounds can any of us

tell ourselves that we are above this human flaw? Should we tell ourselves that

our minds are somehow more aesthetically and morally aware or more disciplined,

and are therefore immune to such delusions? I’m not aware of any logical

grounds for reaching that conclusion about myself or anyone else.

In fact, evidence

revealing this capacity for rationalization in human minds – some of the most

brilliant of human minds – litters history. How could Pierre Duhem, the

brilliant French philosopher, have written off relativity theory just because a

German proposed it? (In 1905, Einstein was considered a German.) How could Martin

Heidegger or Werner Heisenberg have accepted the Nazis’ propaganda? The Führer

principle! "German" science! Ezra Pound, arguably the best literary

mind of his time, propagandizing on Italian radio for Fascism!

George Bernard Shaw (credit: Wikimedia

Commons)

Jean-Paul Sartre (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

How could George

Bernard Shaw or Jean-Paul Sartre have become apologists for Stalin? So many geniuses

of the academic, scientific, and artistic realms fell into this trap. Once we

understand how cognitive dissonance reduction works, the answer is painfully

obvious. Brilliant thinkers are just as brilliant at self-comforting thinking –

namely, rationalizing – as they are at clear, critical thinking. And the most

brilliant specious terms and fallacious arguments they construct – the most

convincing lies they tell – are the ones they tell themselves.

The most plausible,

cautious, and responsible reasoning I can apply to myself leads me to conclude

that the ability to reason well in formal terms guarantees nothing in the realm

of practical affairs. Brilliance at formal thinking has been just as quick to

advocate for totalitarianism and tyranny as it has for pluralism and democracy.

If we want to survive, we need to work out a moral code that counters at least

the worst excesses of the human flaw called rationalization,

especially the forms found in the most intelligent people.

Rationalism is a

regular precursor to intolerance. Rationalism in one stealthy form or another

has too often turned into rationalization, a dangerous affliction of human

minds. The whole design of democracy is intended to remedy, or at least

attenuate, this flaw in human thinking.

In a democracy,

decisions for the whole community are arrived at by a process that combines the

carefully sifted wisdom and experience of all, backed up by references to

observable evidence and a process of deliberate, open, cooperative decision-making.

One of the main

intentions of the democratic model is to handle subversive, secret groups. In

this way, democracy simply mirrors Science. In Science, no theory gets accepted

until it has been tested repeatedly, and the results have been peer-reviewed.

There are no elites who dictate what the rest must think. Focus on observable

evidence that all can see, and then discuss what it means.

While some of my

argument against rationalism may not be familiar to all readers, its main

conclusion is familiar to Philosophy students. It is Hume’s conclusion. He said

long ago that verbal arguments that do not begin from material evidence, but

later somehow claim to arrive at conclusions that may be applied to the

material world can be “consigned to the flames.”5 Cognitive

dissonance theory only gives modern credence to Hume’s famous conclusion.

Rationalism’s

failures lead to the conclusion that its way of ignoring the material world or

trying to impose a preconceived model on the world, doesn’t work. Rationalism

can’t serve as a reliable base for a full philosophical system. Its flaws are

just too blatantly obvious. Its way of progressing from imagined idea to imagined

idea, without reference to physical evidence, is too likely to end in

rationalization instead of rationality.

Finding a complete, life-regulating system of ideas – a moral philosophy – is far too important to our well-being for us to risk our lives on a beginning point that so much historical evidence says is deeply flawed. In order to build a universal moral code, we need to begin from a better base model of the human mind.

But we’ve seen that a

beginning based on sensory impressions gathered from the material world – Empiricism

– doesn’t work either. It can’t adequately describe the thing doing the

gathering. Besides, if we lived by Empiricism – that is, if we just gathered

experiences – we would become transfixed by what’s happening around us. At

best, we would be sense data collectors, recording and storing bits of

experience, but with no idea of what to do with these experiences and memories,

how to do it, or why we would even bother.

In the largest view of ourselves, however, we need concepts/theories in order to make decisions and act. Without mental models to guide us, we’d have no way to form plans for avoiding the same catastrophes our forebears spent so long learning (by pain) to avoid. If both Rationalism and Empiricism turn out to be shaky models on which to base a moral philosophy, then where do we turn?

The answer is complex

enough to deserve a chapter of its own.

Notes

1. Elliot

Aronson, The Social Animal (New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and

Company: 1980), pp. 99–106.

2. Virginia

Stark-Vance and Mary Louise Dubay, 100 Questions & Answers about

Brain Tumors (Sudbury, MA:Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2nd edition,

2011).

3. “G.E. Moore,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia.

Accessed

April 5, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G.e._Moore.

4. “Herbert

Spencer,” Wikipedia, the Free

Encyclopedia. Accessed

April 6, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Spencer.

5. David Hume, An

Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, cited in Wikipedia article

“Metaphysics.” Accessed April 6, 2015.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysics#British_empiricism.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.