Chapter 3. (continued)

A

flawed view of the world can lead one to a lifetime of error and misery.

Marxism’s biggest error is its assertion that everything is political. It may

be that art and journalism can be shown to be influenced by the political

philosophy of the journalist or artist. But for Marxists, all human activities,

even artistic ones, are either helping to advance the Marxist cause or hindering

that cause. Attempts to install Marxist regimes have also all made available

the political machinery by which totalitarianism may be put in place. All political debate is really just revisionism, they claim. Political dissent is not acceptable. Sadly, we

have seen that once the controls for that machinery are available for the seizing, under whatever pretext, a “seizer” always

arises.

But science

is about reality, the reality that comes even before political or artistic

activities begin. If we assert, as some Marxists do, that science must bow to

the will of the people, we inevitably begin to tell our scientists what we want

them to conclude, instead of asking them what the evidence seems to show.

A

clear example is the doctrine called Lysenkoism

in Soviet Russia. In that nation in the 1920s, the official state position was

that human nature itself could be altered and humans made into perfect “socialist

citizens” by changing their outward behavioural traits. If they were made to

act like utterly selfless socialist citizens, they would become so, even in

their genetic programming. This government position required that the Darwinian

view of evolution be overruled because politics must rule science.

Darwin

had said that members of living species do not acquire genetic changes from having

their external traits altered; living things change their natures only when

their gene pools are altered by the processes of genetic variation and natural

selection over many generations. In its determination to create what they

called “socialist citizens”, Soviet Communism required people to believe that the acquired

characteristics of an organism—for example, the state of shrub being leafless

as a result of its leaves having been picked — could be inherited by that organism’s descendants.1 For

years, Soviet agriculture was all but crippled by the party’s attempts to make

its political “truism” be true in material reality, for crops and livestock,

when it simply wasn’t.

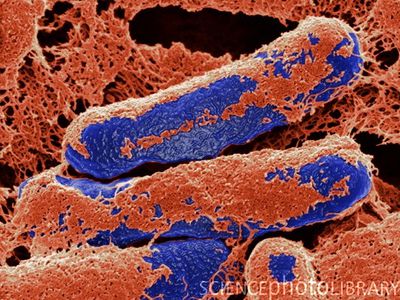

Clostridium botulinum.

Another

more general example of the dangers posed by an inaccurate picture of reality

can be seen in the common activity of home canning. I may think I know all

about bacteria and how to can foods at home in sealer jars. If I’ve looked through

microscopes, I may be confident my picture of the microscopic level of reality

is a true one. But if my knowledge of home canning covers only common bacteria,

my knowledge may prove to be a dangerous thing. The usual boiling-water bath

for foods canned in jars does kill most bacteria, but for a few microbes,

boiling is not enough. Botulism is nothing to be played around with. Botulinum

bacteria can be boiled to death, but their deadly toxins can survive boiling. My

partial and inadequate set of beliefs about home canning might get me killed.

Or

consider a few even more basic examples. Even my senses sometimes are not to be

trusted. I may believe that light always travels in straight lines. I may see,

half immersed in a stream, a stick that looks bent at the water line, so I

believe it to be bent. But when I pull it out, I find that it is straight. If I

am a caveman trying to spear fish in a stream, blind adherence to my ideas

about light will cause me to starve. I will overshoot the fish every time,

while the girl on the other shore, a better learner, cooks her catch.

I

can immerse one hand in the snow and keep the other on a hand warmer in my coat

pocket. If I then go into a cabin to wash my hands in tepid water, I find that

one hand senses the water is cold, the other, that it is warm. Can I not trust

my own senses?

When

we seek to find some things in our experience that we can believe in

absolutely, we are stopped by questions like “What do I really know?” and “How

can I be sure of the things that I think I know?” and “Can I even be certain of

what I see, hear, and touch?” We

are deeply aware that we need a reliable core around which we can build the

rest of our belief system or we may, sometime down the road, suddenly find that

a whole set of ideas, and the ways of living the system implies, are dangerous

illusions.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.