Chapter 5. (continued)

A Doberman Pinscher

In a

more scientific example, I will also mention our Doberman Pinscher–cross pup.

Rex was basically a good dog, but he was a mutt, a Doberman cross we acquired because

one of my aunts could not keep him. People often remarked that he looked like a

Doberman, but his tail was not bobbed. This got me curious. When I learned that

most Dobermans had had their tails bobbed for many generations, I wondered why

the tails, after so many generations of bobbing, had not simply become

shortened at birth. I asked a Biology teacher at my high school, but his answer

only confused me. Actually, I don’t think he understood the crucial features of

Darwinian evolution theory himself.

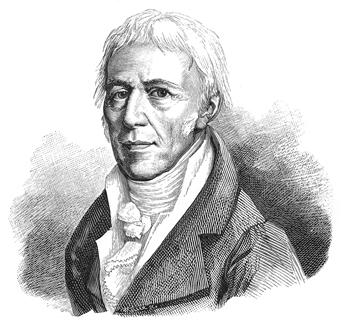

Jean-Batiste Lamarck.

Once

I got to university, I took several biology courses. Gradually at first, and

then in a breakthrough of understanding, I came to realize that I had been

thinking in terms of the model of evolution called Lamarckism. At first I did not want to let go of this cherished

opinion of mine.

I had always thought of myself as progressive, modern,

scientific; I did not believe in creationism. I thought I knew how evolution

worked and that I was using an accurate understanding of it in all of my

thinking. It was only after I had read more and seen by experience that bobbing

dogs’ tails did not cause their pups’ tails to be any shorter that I came to a

full understanding of Darwinian evolution.

Evolution

for all species proceeds by the combined processes of genetic variation and

natural selection. It doesn’t matter how often the anatomies of already

existing members of a species are altered; if their gene pool doesn’t change,

the next generation will, at birth, basically look pretty much like their

parents did at birth. Chopping off a

dog’s tail doesn’t change the genes it carries in the sex cells that govern how

long the pups’ tails will be. Under Lamarckism, by contrast, an animal’s genes are

pictured as changing because the animal’s body has been injured or stressed in

some way. Lamarckism says a chimp, for instance, will pass genes for larger arm

muscles on to its young if the parent chimp has had to use its arm muscles a

lot.

But

Darwinian evolution gives us what we now see as a far more useful picture. In

nature, individuals within a species that are no longer well camouflaged in the

changing flora of their environment, for example, become easy prey for

predators and so they never survive long enough to have babies of their own. Or

ones that are unable to adapt to a cooling climate die young or reproduce less

efficiently, while their thicker-coated, stronger, smarter, or better

camouflaged cousins flourish.

Then,

over generations, the gene pool of the local community of that species does

change. It contains more genes for short, climbing legs or long, running legs

or short tails or long tails or whatever the local environment is now paying a

premium for. Gradually, the anatomy of the average species member changes. If

short-tailed members have been surviving better for the last sixty generations

and long-tailed members have been dying young, before they could reproduce, the

gene pool changes. Eventually, as a consequence, there will be many more

individuals with the shorter tail that has now become a normal trait of the

species.

Pondering

Rex’s case helped me to absorb Darwinism. My understanding grew and then, one

day, through a mental leap, I suddenly “got” the newer, better model. A model I

hadn’t understood suddenly became clear, and it gave a deeper coherence to all

of my ideas and observations about living things. For me, Lamarckism became

just an interesting footnote in the history of science, sometimes still useful

because it showed me one way in which my thinking, and that of others, could go

wrong.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.