The

science of Psychology,

in particular, has cast a harsh spotlight on the inconsistencies of rationalism.

The moral philosophers’ hope of finding an empiricist foundation for a moral system

was broken by thinkers like Quine and Gödel. Rationalism’s flaws were just as

clearly shown up by psychologists such as Elliot Aronson and Leon Festinger.

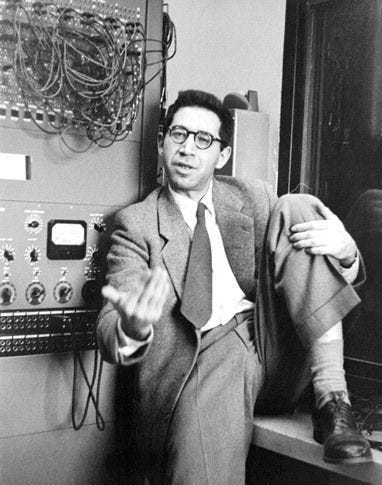

Leon Festinger.

Elliot Aronson.

Aronson

was Festinger’s student, who went on to win much acclaim in his own right. They

both focused their work on cognitive dissonance theory, which describes

something fairly simple, but its consequences are profound and far-reaching.

Basically, the theory says that the inclination of the human mind is always

toward finding good reasons for justifying what we want to do anyway, and even

more vigorously-argued reasons for the things we’ve already done. (See Aronson’s

The Social Animal.1)

What

it says essentially is this: a human organism tends, actively, insistently, and

insidiously, to think and act so as to perceive and affirm itself as being

consistent with itself. In every action the mind directs the body to perform,

and especially in every phrase it directs the body to utter, it shows the

desire to remain consistent with itself. In practice, this means humans tend to

find and state what appear to themselves to be good reasons for doing what they

have to do in order to maintain the conditions of life that they have become

comfortable with. The individual human mind constantly strives to make theory

match practice or practice match theory—or to adjust both—in order to reduce

its own internal clashing—that is, what psychologists call cognitive dissonance.

A

novice financial advisor who used to speak disparagingly of all sales jobs will

soon be able to tell you with heartfelt sincerity why every person, including

you, ought to have a carefully selected portfolio of stocks. The physician adds

another bank of expensive therapies—all of doubtful effectiveness—every year

or so to his repertoire. The plastic surgeon can show with argument and

evidence that all of the cosmetic procedures he performs should be covered by

the country’s health-care plans because his patients aren’t spoiled and vain,

they are “aesthetically handicapped.” The divorce lawyers are not setting two

people who used to love each other at each other’s throats. They’re merely defending

the clients’ best interests, while the clients’ misery and despair grow more

profound every week. The cigarette company executive not only finds what he

truly believes are flaws in cancer research, he smokes over two packs a day.

The general sends his own son to the front. And his mother-in-law’s decent

qualities (not her rude ones) become more obvious to him on the day he learns that

she owns over ten million dollars’ worth of real estate. (All that worry! No

wonder she’s rude.)

The Philosophy

professor, whose mind is trained to seek out inconsistencies? He once said he

believed in the primacy of the rights of the individual over any group’s

rights. He sought to abolish any taxes that might be used to pay for social

services. Private charities could do such work, if it needed to be done at all.

But then his daughter, who suffers from bipolar disorder and who sometimes secretly

goes off her medications and runs away from all forms of care, no matter how

loving, runs off and becomes one of the homeless in the streets of a distant

city. She is spotted and saved from almost certain death by alert street

workers, paid (meagrely) by the government. Now he argues for the

responsibility of citizens to pay taxes that can be used to create programs

that hire street workers who look out for and look after the destitute and

unfortunate in society.

In addition, he once considered euthanasia to be totally immoral. But now his aging father with Alzheimer’s disease has been deteriorating for over five years. Professor X is broke, sick, and exhausted himself. He longs for the heartache to be over. He knows that he cannot keep caring personally, day in and day out, for the needs of this now gnarled, unrecognizable, pathetic creature for very much longer. Even Dad, the dad he once knew, would have agreed. Dad needs and deserves a gentle needle. Professor X is certain of it, and he tells his grad students and colleagues so during their quiet, confidential moments.

In addition, he once considered euthanasia to be totally immoral. But now his aging father with Alzheimer’s disease has been deteriorating for over five years. Professor X is broke, sick, and exhausted himself. He longs for the heartache to be over. He knows that he cannot keep caring personally, day in and day out, for the needs of this now gnarled, unrecognizable, pathetic creature for very much longer. Even Dad, the dad he once knew, would have agreed. Dad needs and deserves a gentle needle. Professor X is certain of it, and he tells his grad students and colleagues so during their quiet, confidential moments.

We don’t like seeing ourselves as hypocrites. We don’t like living with nagging feelings of cognitive dissonance. Therefore, we tend to favour and be drawn to ways of thinking, speaking, and acting that will reduce that dissonance, especially in our internal pictures of ourselves. Inside our heads, we need to like ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.