Now, all of this still may sound academic and far removed from the lives of ordinary folk. But the truth is otherwise. When a society’s sages

can’t guide its people, they look elsewhere for moral leaders. When the “wise”

respond to their fellow citizens’ queries about morality with jargon and

equivocation, others—some of them very unwise—jump in to fill people’s needs.

So we ask: how did the eroding of the West’s moral systems that

followed the rise of Science affect people living through real events? Let’s

consider one harsh example.

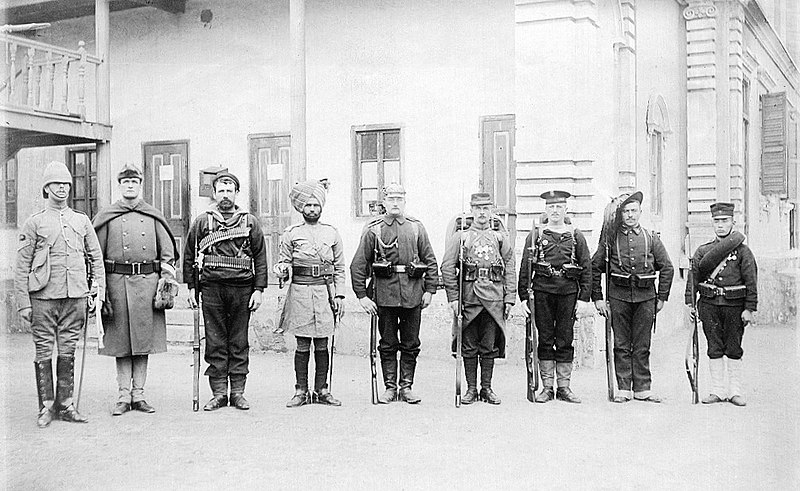

World

War I, young German soldier (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

By the early twentieth century, the impacts of the ideas of Darwin

and Freud, and of Science generally, had arrived. Social scientists and

philosophers were left scrambling to understand what new moral code, if any,

was implied for humanity by these new ways of seeing the world. Is Science

telling us anything about what is right? Answers on every side were

contradictory and confusing. Then, following too soon, in a bitter or perhaps

inevitable irony, real-world political events broke out of control. In 1914,

World War I arrived; it became the major test of the moral systems of the new scientific

societies of the West.

World

War I recruitment poster (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

When World War I began, in the cities and towns of

Europe and in the cities of all other countries that were attached to the main

belligerents, banners flew, troops marched, bands played, and huge crowds of

men, women, and children all shouted for joy. A few sober people raised

objections for one set of reasons or another, but they were drowned out in the

din. In every nation involved, people fell easily into viewing the human race

as being made up of "us" and "them", as people tend to do

in wartime, and people easily began to say to their neighbors that, finally,

the superior armies and ideals of their way of life were going to sweep aside

the barbaric, backward armies and ideals of their nation’s enemies.

Exhorted in speeches by their leaders and by

writers in the media to stand up for their homelands, the men of Italy,

Germany, France, Britain, Austro-Hungary, and Russia, along with all their

allies, absorbed the jingoistic stories being told in their newspapers and

signed up to fight. Competing narratives about Europe and its history had finally

brought the European tribes into head-on confrontation. "They" had their view of how the future should go. "We" had a very different one. Science said, "You're both right." or sometimes, "Don't look at me. I'm not involved."

Anti-German propaganda

poster (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

My country, Canada, was part of the British Empire

in 1914, and Canadians were just as eager as any of the loyal subjects in London,

England. Young men leaped out of the crowds lining the streets to march in step

with the parades of soldiers going by. Many of them were worried that by the

time they got through their training and on to Europe, the fighting would be

over. Girls clustered around men in uniform who came back to visit their

workplaces or colleges or even high schools before shipping out. Old ladies out

shopping, by 1916, would spit on any young man of military age who was not in

uniform.