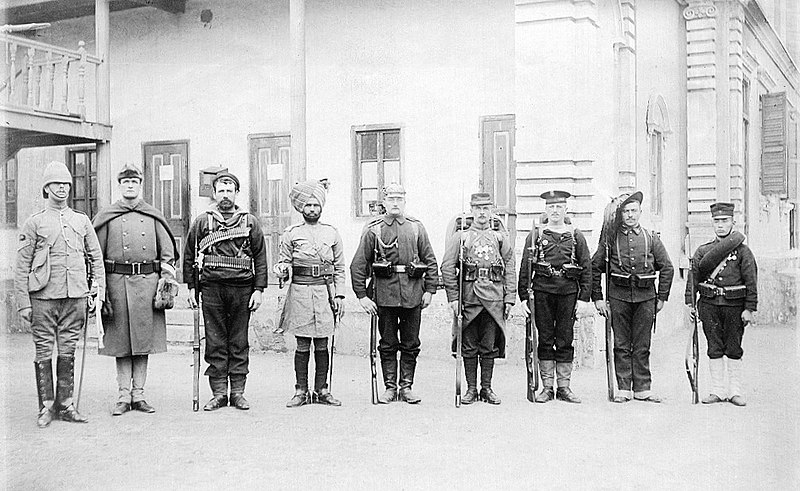

soldiers of the 8 nations alliance (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

In the face of all the criticism of social science, some social

scientists have taken an even more aggressive stance. They have argued that no

science, not even Physics, is truly objective. Complex, culturally-based biases

shape all human thinking—even, they say, the thinking of the physicists and

chemists.

Thus, they argue that the overarching position called moral relativism is the only logical

conclusion to be drawn from the whole body of social science research, or all

research in all fields, for that matter. We can try to observe and study human

societies and the belief systems they instill in their members, but we can’t

pretend to do such work objectively. We come to it with eyes already programmed

to see the details considered “significant” under the models and values we

absorbed as children. Each researcher’s model of what human society is—or

should be—lies deeper than her ability to articulate thoughts in words or even

simply to observe. Our biases can’t be suspended; they prefigure our ability to

think at all.

This is the stance called social

constructivism. In its view, thought filters are acquired from our culture

(parents, teachers, etc.) as we develop, and with these tools, we string

together sense data—the ones that we have been told matter—until, moment by moment, we form a picture of “reality.” But

the whole of reality is much more detailed and complex than the set of sights

and sounds we are paying attention to. And other people, especially those from

other cultures, construct their own pictures of reality, some of them radically

different from ours, but still quite workable. People from other cultures have

morés and ways of seeing reality that differ from our ways, but their ways do

work for them.

In support of their claim that all human perspectives on the human

aspects of the world are hopelessly biased, social scientists point out that

while careful descriptions of events in a given society are possible, and

generalizations about apparent connections between events in that society are

possible, law-like statements about how moral codes and morés for all human societies

work continue to elude us.

Some social

scientists go so far as to claim there aren’t any “facts” in any of our

descriptions any of the any events of the past, even of the events happening

around us now. There are only details selected by us, but guided by the values

we learned as children. We string these details we do notice together to form various

narratives, any one of them as valid as any other one. At the highest level of

generality on what morality is, many social scientists not only have had

nothing to say, they insist that nothing “factual”—that is, nothing objectively

true—can

be said. Each of us

is trapped inside of her or his version of reality, and there is nothing we can

do about that. Science is just a Euro-based set of opinions that seem to be

working some of the time …for now.

Scientists in the

sciences other than the social ones continue to argue that there is an

empirical, material reality out there that is common for all of us and Science

is the only reliable way we have to study and understand that reality. Thus, most

scientists will admit that they can’t give a very good explanation or model for

what moral values are – if such things can even be said to exist – but the idea

that Science can’t give us any reliable insights into how any parts of reality

work is nonsense. Science works. Its successes have been so many that no sane

person can doubt that claim any longer.

These arguments called the Science

Wars continue to rage. There’s not enough space here to go into even five percent

of the whole controversy. But the point is that Yeats was right: the

best really can lack all conviction. They can read about honour killings and remark

calmly, “Well, that’s their culture.” In fact, to many thinkers in the

humanities and social sciences today, all convictions are temporary and local.

(One more recent, sensible, and useful compromise position is taken by Marvin

Harris in Theories of Culture in Postmodern

Times.)5

This has been the scariest consequence of the rise of Science: moral

confusion and indecision among our elites. It began to become serious in the

West in the nineteenth century, after Darwin and Nietzsche, but here we are in

the twenty-first and, if anything, the crisis of moral confidence appears to be

worsening.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.