Chapter 11. (continued)

The loss of much of the Romans’ practical skill, especially their

administrative abilities, kept Europe from growing dominant worldwide until the

Renaissance. At that time, these more worldly values were reborn due to a

number of factors familiar to scholars (e.g., the fall of

Constantinople, the rise of science, the discovery of the Americas, etc.). Or

perhaps, in another more causally focused view, we could say that the Christian

way, which required every citizen to respect every other citizen, built Western

society’s levels of overall efficiency up to a critical mass that made the

flowering of Western civilization now called the Renaissance inevitable. The

new hybrid value system worked: Greek theoretical knowledge and Roman practical

skills in a Christian social milieu integrated into a single, functioning whole.

Hanseatic League, city of Lubeck

It took over a thousand years for people whose lives focused on

worldly matters, instead of only on seeking salvation in the world after death,

to be seen as good Christian citizens in the community. Artists, architects,

even merchants, explorers and conquistadores finally could do what they had

always done, though now as ways of glorifying God. But in evolutionary terms, a

thousand years is almost nothing.

It is interesting to note the intricacies of the socio-historical

process. Even societies that seem to have reached equilibrium always contain a

few individuals who restlessly test their society’s accepted world view,

values, and morés. These people and their disciples are often the young, which suggests

adolescent revolt plays a vital role in the evolution of society. Teenagers

make us look at our values and, once in a while, we realize that one of those

values is due for overhaul or even retirement. Teenage revolt serves a larger

purpose in the evolutionary process of cultural change.

However, it’s more important to understand that many people in the

rest of society see these new thinkers and their followers as delinquents, and

only a very few see them as valuable. It is even more important to see that the

numbers involved on each side don’t matter. What does matter is, first, whether

the new thinkers’ ideas attract at least a few followers and, second, whether

the ideas work, which is to say, whether the followers then live better,

healthier, happier lives than the rest of the society.

A society, like any living thing, needs to be opportunistic,

constantly testing and searching for ways to grow, even though many citizens in

its establishment may resent the means by which it does so and may do everything

in their power to quell the process. Often they can, but not always. For

Western society, until the practical features of its classical beliefs were

integrated with its more humane Christian ones, Europeans largely did not

support those whose ideas and morés focused on life in this material world.

Artists, scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs are, by their

very nature, eccentric. They don’t support the status quo, they threaten it.

But the dreamers are the ones who move the rest forward toward newer, better

ways of doing things. They only really flourish in a society that not only

tolerates but takes pride in its eccentrics. In a truly dynamic society,

cleverness is melded with kindness and acceptance of those who are different.

In short, European culture needed a thousand years to even begin to “get its

act together” and meld all of its values into a single smoothly functioning

whole.

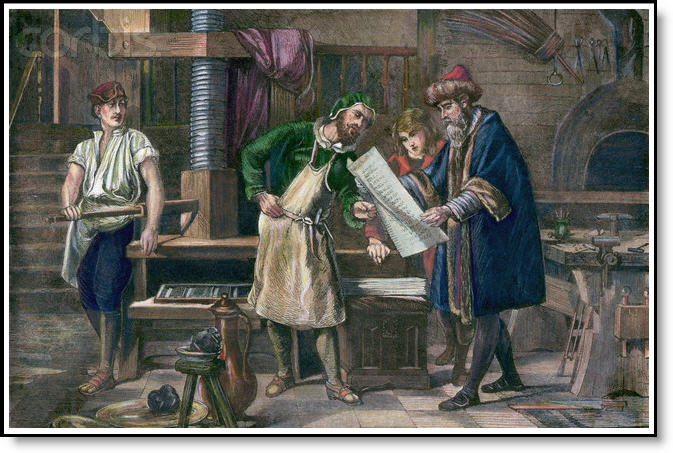

Gutenberg checking a press proof in his shop (circa 1440)

To flourish, a society must use resources and grow when it has

opportunities to do so, or it will lose out later when events in the

environment grow harsher or when competition gets fiercer and it has few savings accumulated. How do new,

improved ways of doing things become established ways of doing things? One

means is by war, as has been mentioned. But the peaceful mechanism can also work,

and it is seen in tolerant societies when the people who use new ways are

allowed to do so undisturbed, and then they just live better. At that point,

the majority begins to pay attention and to take up the eccentrics’ ways.

This market-driven way is the way of peaceful cultural evolution,

the alternative to the war-driven one. Humans have taken a long time to reach

it, but as a species, we are almost there.

Now, where are we? What has been shown in this chapter is that

values endure down generations. In the nations of the West, Christian

respect and compassion took a thousand years to synthesize with the Greek abstract

thought and Roman practicality, but once the Western nations learned to see

science, exploration, and commerce as ways of glorifying God, material progress

had to result. Whether that progress produced a concomitant moral progress I

will deal with later in this book. For now, let’s keep following what really

did happen in the West and save what it meant in moral terms for a later

chapter.

Notes

1.

Matthew Allen Fox, The Accessible Hegel

(Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2005).

2.

Edith Hamilton, Mythology: Timeless Tales

of Gods and Heroes (New York, NY: Warner Books, 1999), pp. 16–19.

3. Edward Gibbon, History of

the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 1 (1776; Project Gutenberg).

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/731/731-h/731-h.html.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.