Chapter 12. (continued)

French chemist Antoine Lavoisier with his wife, Marie

This scientific way of thinking was further employed by geniuses

like Isaac Newton, William Harvey, Michael Faraday, Antoine Lavoisier, and

others. Its gurus piled up successes in the hard market of physical results. Of

those who resisted the new way, some were converted by reason, some went down

in military defeats, some worked out compromises, and some just got old and

died, still resisting the new ways and preaching the old ones to smaller and

smaller audiences. The Enlightenment, as it is now called, had taken over.

Other societies that operated under world views in which humans

were thought to have little ability to control the events of life are to be

found in all countries and all eras of history, but we don’t need to discuss

them all. The point is that the advancing worldview by the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries, around the planet, was the one we call scientific,

the Enlightenment view.

The one significant interruption in the spread of the Enlightenment’s

values is the period called the Romantic Age. The meaning of this time is still

being debated, but in my model, which sees a kind of cultural evolution in the

record of human history, there are only a couple of interesting points to note

about the Romantic Age (roughly, the mid-1700s to the mid-1800s).

The Abbey in the Oakwood (Friedrich) showing Romantic imagination and emotion

First, it reaffirmed and expanded the value of the individual when

the Enlightenment had gone too far and made duty—to the family, the group, or

the state—seem like the only “reasonable” value, the one that should motivate all

humans as they chose their actions. Romanticism asserted forcefully and

passionately that the individual had an even greater duty to his own soul. I

have dreams, ideas, and feelings that are uniquely mine, and I have a right to

them. Paradoxically, this philosophy of individualism can be very useful for a whole

society when it is spread over millions of citizens and over decades and generations.

This is because even though most of the dreamers produce little that is of any

practical use to the larger community and some even become criminals, a few

create beautiful, brilliant things that pay huge material, political, and

artistic dividends.

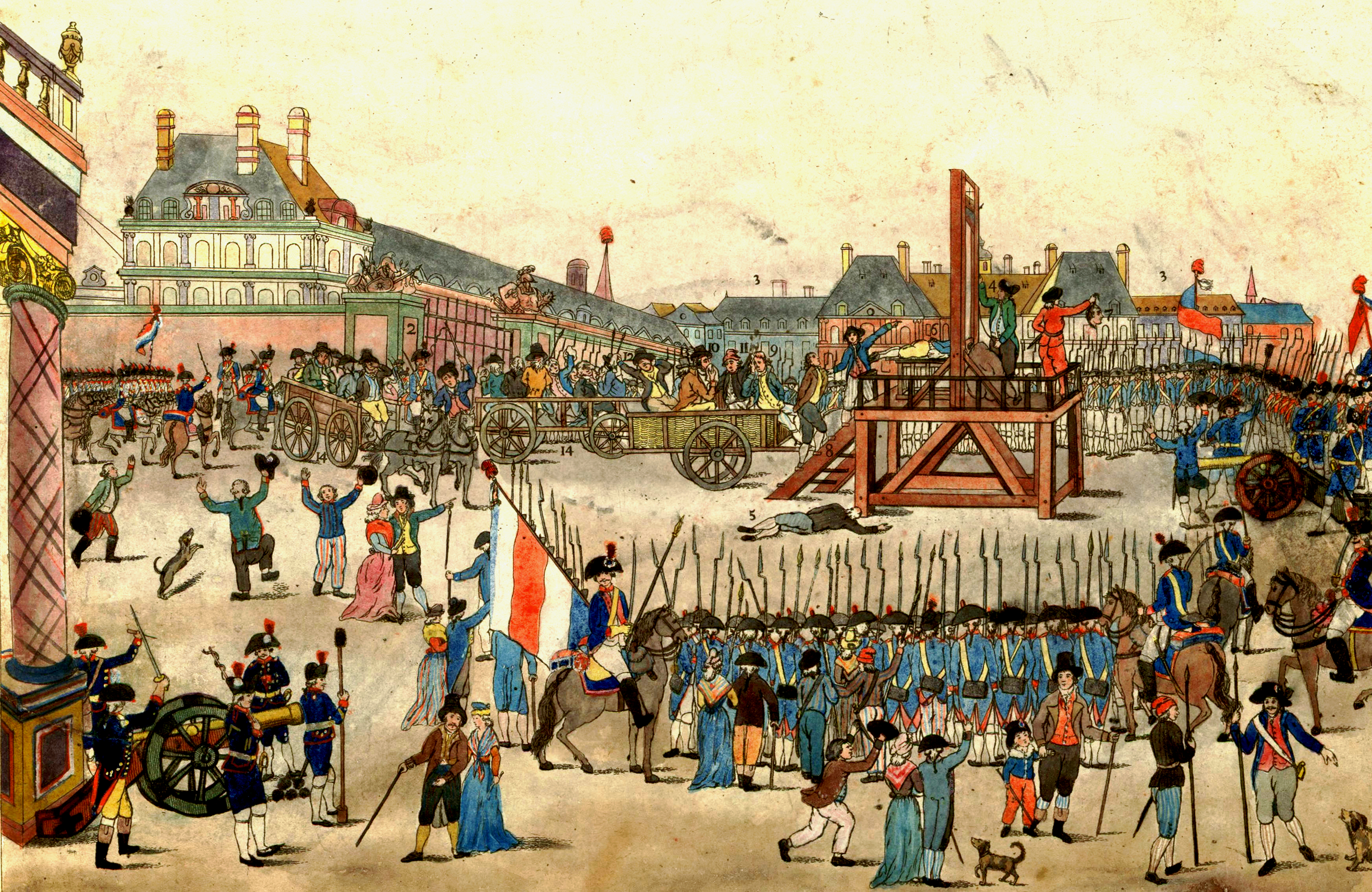

Guillotining of Robespierre during the French Revolution

In the second place, however, we should note that as a political

philosophy, Romanticism produced some painful excesses. In France, for example,

the citizens were indeed passionate about their ideals of liberty, equality,

and brotherhood, but once they had overthrown the hereditary kings and nobles

and set up an idealistic people’s republic, they didn’t know how to administer

a large, populous state. In a short while, they fell into disorder. Then they simply

traded one autocrat for another (Louis XVI for Napoleon). Their struggle to

reach an enlightened view of the deepest nature of humans, and to understand how

a system of government that resonates with humans’ deepest nature might be

instituted, took longer than one generation to evolve. But the French did begin

evolving resolutely toward it. After Napoleon’s fall, a new Bourbon dynasty was

instituted, but the powers of the monarchs were now severely limited, and after

some more turmoil, the new Bourbon gang were also ousted. Democracy evolved –

in erratic ways and by pain, but it evolved and grew strong, and is still

evolving in France, as is the case in all modern states.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.