Chapter 11 – Pre-Renaissance Worldviews

Every society must work out and articulate a view

of the physical universe, a way of seeing the world, a way that then becomes

the base on which the society’s value system is to be built. This is no minor

matter; while philosophers may dally over the questions in a theoretical way, real

folk have to deal with life. They have to have some code in place that helps

them decide how to live. World view, values, and behaviors must form a coherent

system under which each individual is empowered to make decisions and take

action so the entire society can efficiently operate, cooperate, and survive in

its always changing, always demanding environment.

All societies know this in some deep way. Societies

up until our time have integrated their worldviews, values, and morés to the

extent that they have because people everywhere know implicitly that their worldview

is their guide when they are trying to decide whether an act that feels morally

right is practicable – whether what is called morally right can work in reality. No one wants to strive for what

he/she believes does not exist.

Therefore, before we begin constructing this new

system, we need to get our thinking into the necessary mindset by considering

the most salient peaks in the histories of some societies of the past, in order

to see how systems of world views, values, and behaviors coordinate and evolve.

We shall get into thinking carefully about human societies and their ways of

life by studying the past.

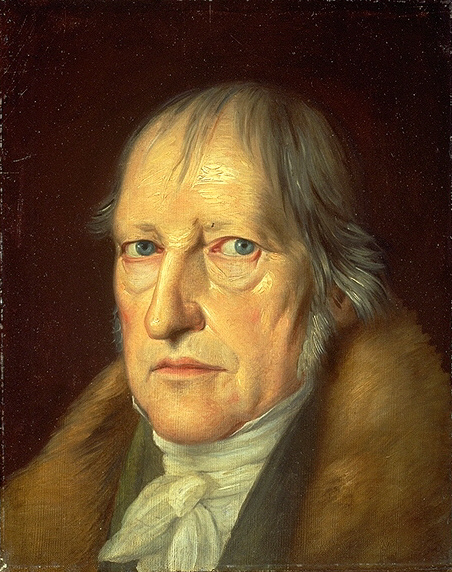

G.W.F. Hegel (artist: Jakob Schlesinger, via

Wikimedia Commons)

In this chapter, Philosophy students will notice

parallels between aspects of my ideas and the philosophy of Hegel, and I admit

freely that similarities exist. But I also have some major points of

disagreement with Hegel, which I will explain along the way. For those readers

who are not Philosophy students, please note that I will give only a very quick

version of my understanding of Hegel. If you find the ideas presented here

interesting, you really should give Hegel a try. His writing is difficult, but

not impossible, and it has also been interpreted by some disciples who write

more accessibly.1 Now back to our analysis of the world views,

values, morés, and behavior patterns that are discernible in the history of

some of the societies of the West.

“Saturn devouring one of his children” (Goya)

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

For instance, let’s consider the ancient

Greeks, the ones who came long before Socrates’ time. They portrayed the

universe as an irrational, dangerous place. To them, the gods who ran the

universe were capricious, violent, and cruel, a phrase which also described the

Greeks’ worldview. Under this view, humans could only cringe fearfully when

confronted with the gods’ testy humors. Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Ares, Hades,

Athena, Apollo, and the rest were all lustful, jealous, cruel, and unpredictable.

Zeus especially wielded thunderbolts; Poseidon could inflict earthquakes;

Apollo, plagues.

But as Greek

culture advanced, the Greek worldview evolved. By the Periclean Age, Greek

plays were portraying humans challenging the gods. After all, they had been

given the secret of fire by their patron, Prometheus. As the Greeks' worldview

with its attached system of values evolved, it guided them toward a smarter,

braver lifestyle. They began trying to explain reality in ways that made room

for people to understand and manipulate the events in their world, not cringe

away from them. Once their worldview included those possibilities, they began

to create practical action plans that enabled humans to cause, hasten, or

forestall more and more events in the world. They tried out the daring action

plans, and when some worked, more daring plans followed. (Edith Hamilton

articulates these ideas well.2)

It is important

to see that human individuals and groups will normally not attempt any action

they think of as taboo. Ancient tribes who happened upon an action that seemed

contrary to, or outside of, what was appropriate for humans in their worldview

only grew upset and fearful. Whether the action got results or not, the only

thing most of those people wanted to learn was how to avoid putting themselves

in the same situation again. They sought to avoid it for fear of bringing the

gods’ wrath down on them. Once in a while, a genius might question his

society’s worldview and even describe an alternative one, but he often paid

dearly for such audacity—by being ostracized or put to death.

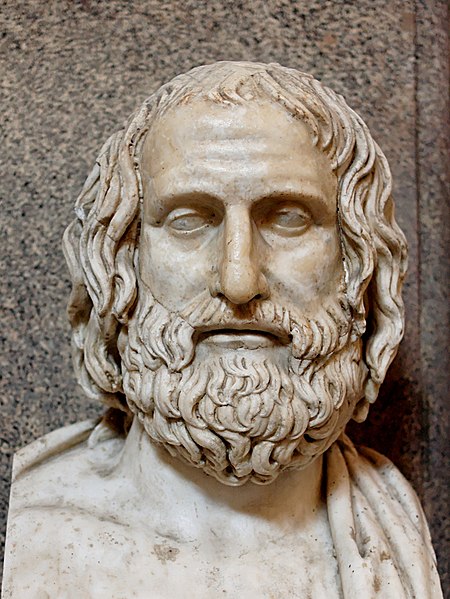

Euripides, Greek

tragic playwright (credit: Marie-Lan Nguyen, via Wikimedia Commons)

However, changes

in a society’s worldview and then in the society’s values and morés can also

evolve more gradually, helped by many lesser geniuses. By the Golden Age of

Athens, philosophers, writers, and artists were offering works that only a few

centuries earlier would literally have been unthinkable. Their worldview had

evolved to allow for at least some degree of human free will. The works of

Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Euripedes, and Pythagoras could only have been

produced under a worldview in which a person could conceive of actions

challenging the orthodox beliefs of the tribe and even the forces of the

universe. Even though the challenge might only rarely succeed, once it did it drew adherents because it worked. It made life better.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.