Marie and Antoine Lavoisier (credit: J. L. David, via Wikipedia)

This scientific way of thinking was used

by geniuses like Newton, Harvey, Faraday, Lavoisier, and others. They piled up

successes in the hard market of practical results. Of those who resisted the new

way, some went down in military defeats, some were converted by reason, some

worked out compromises, and some simply got old and died, still resisting the

new ways and still preaching the old ones to smaller and smaller audiences.

The

Enlightenment, as it is now called, had taken over.

Other societies that operated under world

views in which humans were thought to have little ability to control the events

of life are to be found in all countries and all eras of history, but we don’t

need to discuss them all. The point is that the advancing worldview by the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, everywhere on this planet, was the

one we call scientific, also called

the Enlightenment view. Human minds

can solve anything, they believed. Reason will keep producing new waves of

progress. A Golden Age is coming.

The one significant interruption in the

spread of the Enlightenment’s values is the period called the Romantic Age. The

meaning of this time is still being debated. I see it as a period of adjustment, of finding a new balance.

In the cultural evolution of our species, values and ways of life keep evolving

into more vigorous versions of human society all the time. The Romantic Age was

a period of finding a new balance between values that freed individuals

and values that created stability in communities. But, there are a couple of especially

interesting points to note about the Romantic Age (mid-1700s to the mid-1800s).

Art in the Romantic Age (credit: Caspar David Friedrich, via Wikimedia Commons)

First, Romanticism affirmed and

expanded the value of the individual when the Enlightenment had gone too far. Some

prominent Enlightenment thinkers (Kant especially) had made duty—to one’s family,

city , or state—seem like the prime value, the one that should

motivate all humans as they chose their actions. Romanticism asserted passionately that the individual had a greater duty to her/his

own soul. I have dreams, ideas, and feelings that are uniquely mine, and I have

a right to them.

Note also that, paradoxically, this

philosophy of individualism can be very useful for a whole society when it is spread

over millions of citizens and multiple generations. This is because even though

most dreamers create little that is of practical use to the larger community, and

some even become criminals, a few create brilliant things that pay huge

material, political, and artistic dividends. (Steam engines, vaccines, universal

suffrage, Impressionism, etc.)

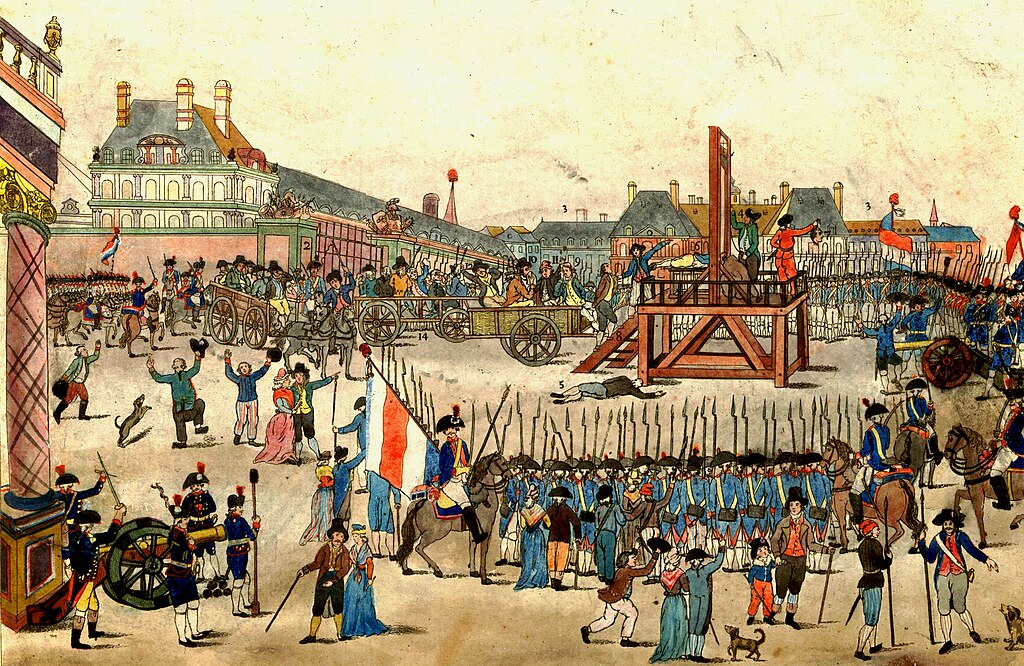

Drawing of guillotining during the French

Revolution (credit: Wikipedia)

In the second place, however, we should

note that as a political philosophy, Romanticism produced painful excesses. In France,

for example, the citizens were indeed passionate about their ideals of liberty,

equality, and brotherhood, but once they had overthrown the hereditary kings

and nobles and set up their people’s republic, they didn’t know how to

administer a large, populous state. In a short while, they fell into disorder and

internal wrangling. Then, as their new state began to unravel, they simply

traded one autocrat for another (Louis XVI for Napoleon). Their struggle to

understand how a system of government that truly harmonized with the best of human

nature could be created took longer than one generation to evolve.

But the French did begin evolving

resolutely toward it. After Napoleon’s fall, a new Bourbon dynasty got control,

but the powers of the monarchs were now much more limited, and after more turmoil,

the Bourbon gang was ousted altogether. Democracy evolved – in erratic ways and

by pain, but it evolved and grew strong, and is still evolving in France, as is

the case in all modern states.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.