Chapter 5 – Bayesianism: How It Works

Thomas Bayes (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The

best answer to the problem of what human minds and human knowing are is that we

are really all Bayesians. On Bayesianism, I can build a universal moral system.

So what is Bayesianism?

Thomas Bayes was an English Presbyterian minister, statistician,

and philosopher who formulated a specific theorem that is named after him:

Bayes’ theorem. His theory of how humans form

tentative beliefs and gradually turn those beliefs into concepts has been given

several mathematical formulations, but in essence it says a fairly simple

thing. We tend to become more convinced of the truth of a theory or model of

reality the more we keep encountering bits of evidence that, first, support the

theory and, second, can’t be explained by any of the competing models of

reality that our minds already hold. (A fairly accessible explanation of Bayes‘

theorem is on the Cornell University Math Department website.1)

Under

the Bayesian view, we never claim to know anything for certain. We simply hold most

firmly a few beliefs that we consider very highly probable, and we use them as

we make decisions in our lives. We then assign to our other, more peripheral

beliefs, lesser degrees of probability, and we constantly track the evidence

supporting or disconfirming all of our beliefs. We accept as given that all

beliefs, at every level of generality, need constant review and updating, even

the ones that seem for long periods to be working well at guiding us in handling

real life.

The

more that a new theory enables a mind to establish coherence within its whole

conceptual system and all its sets of sense-data memories, the more persuasive

the theory seems. If the evidence favoring the theory mounts, and its degree

of consistency with the rest of the beliefs and memories in the mind also

grows, then finally, in a leap of understanding, the mind promotes the theory

up to the status of a concept and incorporates the new concept into its total

stock of thinking machinery.

At

the same time, the mind nearly always has to demote to inactive status some

formerly held beliefs and concepts that are not commensurable with the new

concept and so are judged to be less efficient in enabling the mind to organize

and use its total stock of memories. This is especially true of all mental activities

involved in the kinds of thinking that are now being covered by the new model

or theory. For example, if you absorb and accept a new theory about how your

immune system works, that idea, that concept, will inform every health-related

decision you make thereafter.

In

life, examples of the workings of Bayesianism can be seen all the time. All we

have to do is look closely at how we and the people around us make up, or

change, our minds about our beliefs.

When

I was in junior high school, each year in June I and all the other students of the

school were bused to the all-city track meet at a stadium in West Edmonton.

Student athletes from all the junior high schools in the city came to

compete in the biggest track meet of the year. Its being held near the end of

the school year, of course, added to the excitement of the day.

A

few of the athletes competing came from a special school that educated and

cared for those kids who today would be called mentally challenged. In my Grade

9 year, three of my friends and I, on a patch of grass beside the bleachers,

did a mock cheer in which we shouted the name of this school in a short rhyming

chant, attempted some clumsy chorus-line kicks in step, crashed into each other,

and fell down. I should make clear that I did not learn such a cruel attitude

from my home. My parents would have been appalled. But fourteen-year-olds,

especially among their peers, can be cruel.

The

problem was that one of the prettiest and smartest girls in my Grade 9 class,

Anne, was in the bleachers, watching field events in a lull between track

events. She and two of her friends happened to catch our little routine. By the

glares on their faces, I could see they were not amused. Later that day I

learned that although she had an older brother who had attended our school and

done well academically, she also had a younger brother who was a Down syndrome

child.

I

apologized lamely the next day at school, but it was clear I’d lost all chance

with her. However, she said one thing that stayed with me. She told me that if

you form a bond with a mentally retarded person (retarded was still the word we used in those days), you will soon realize

you have made a friend whose loyalty, once won, is unchanging and unshakable—probably,

the most loyal friend you will ever have. And that realization will change you.

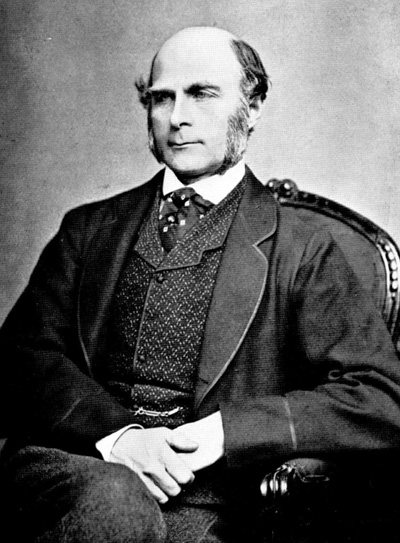

Francis Galton, originator

of eugenics (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

It

was the proverbial thin edge of the wedge. Earlier, I had absorbed some of the

ideas of the pseudo-science called eugenics

from one of my friends at school, and I had concluded the mentally challenged added

nothing of value to the community but inevitably took a great deal out of the

community. What Anne said made me begin to question those assumptions.

Over

years of seeing movies like A Child Is

Waiting and Charlie and of being

exposed to awareness-raising campaigns by families of the mentally challenged,

I began to see them in a different light. Over the decades, they came to be

called mentally handicapped and then mentally challenged or special needs, and the changing

terminology did matter. It changed our thinking.

I

became a teacher, and then, in the middle of my career, mentally challenged

kids began to be integrated into the public school where I taught. I saw with

increasing clarity what they could teach the rest of us, just by being

themselves.

Tracy

was severely handicapped, in multiple ways, mentally and physically. Trish, on

the other hand, was a reasonably bright girl who had rage issues. She beat up

other girls, she stole, she skipped classes, she smoked pot behind the school.

But when Tracy came to us, Trish proved in a few weeks to be the best with

Tracy of any of the students in the school. Her attentiveness and gentleness

were humbling to see. In Tracy, Trish found someone who needed her, and for

Trish, it changed everything. As I watched them together one day, it changed

me. Years of persuasion and experience, by gradual degrees, finally, got to me.

I saw a new order in the community in which I lived, a new view of

inclusiveness that gave coherence to years of observations and memories.

Today,

I believe the mentally challenged are just people. But it was only grudgingly

at fourteen that I began to re-examine my beliefs about them. At fourteen, I

liked believing that my mind was made up on every issue. Then, years of

gradually growing awareness led me to change my view. A new thinking model,

gradually, by accumulation of evidence, came to look more correct and useful to

me than the old model. In a kind of conversion experience, I switched

models. Of course, by gradual degrees, through exposure to reasonable arguments

and real experiences, I and a lot of other people have come a long way on this

issue from what we believed in 1964. Humans can change.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.