We

do not have to believe—as the rationalists say we do—in another dimension of

pure thought, with herds of “forms” or “distinct ideas” roaming its plains, in

order to have confidence in our own ability to reason. By nature or nurture, or

by subtle combinations of the two, we acquire and pass on to our children those

concepts that enable their carriers – that is, us – to survive. In short, reason’s

roots can be explained in ways that don’t assume any of the things that rationalism

assumes.

Now rationalism’s

really disturbing implications start to occur to us. Wouldn’t I love to believe

that there is some hidden dimension in which the forms exist, perfect and

eternal? Of course I would. Then I would know that I was “right.” Then I and a

few simpatico acquaintances might agree among ourselves that we were the only

people truly capable of perceiving the finer things in life or of recognizing

which are the truly moral acts. Our training and natural gifts would have

sensitized us to be able to detect the beautiful and the good. For us to

persuade the ignorant masses would be only rational; considering their incapacity

to figure things out—it would be an act of mercy.

This

view is not just theoretically possible. It was the view of some of the disciples

of G.E. Moore almost a century ago and, even more blatantly, of some of the

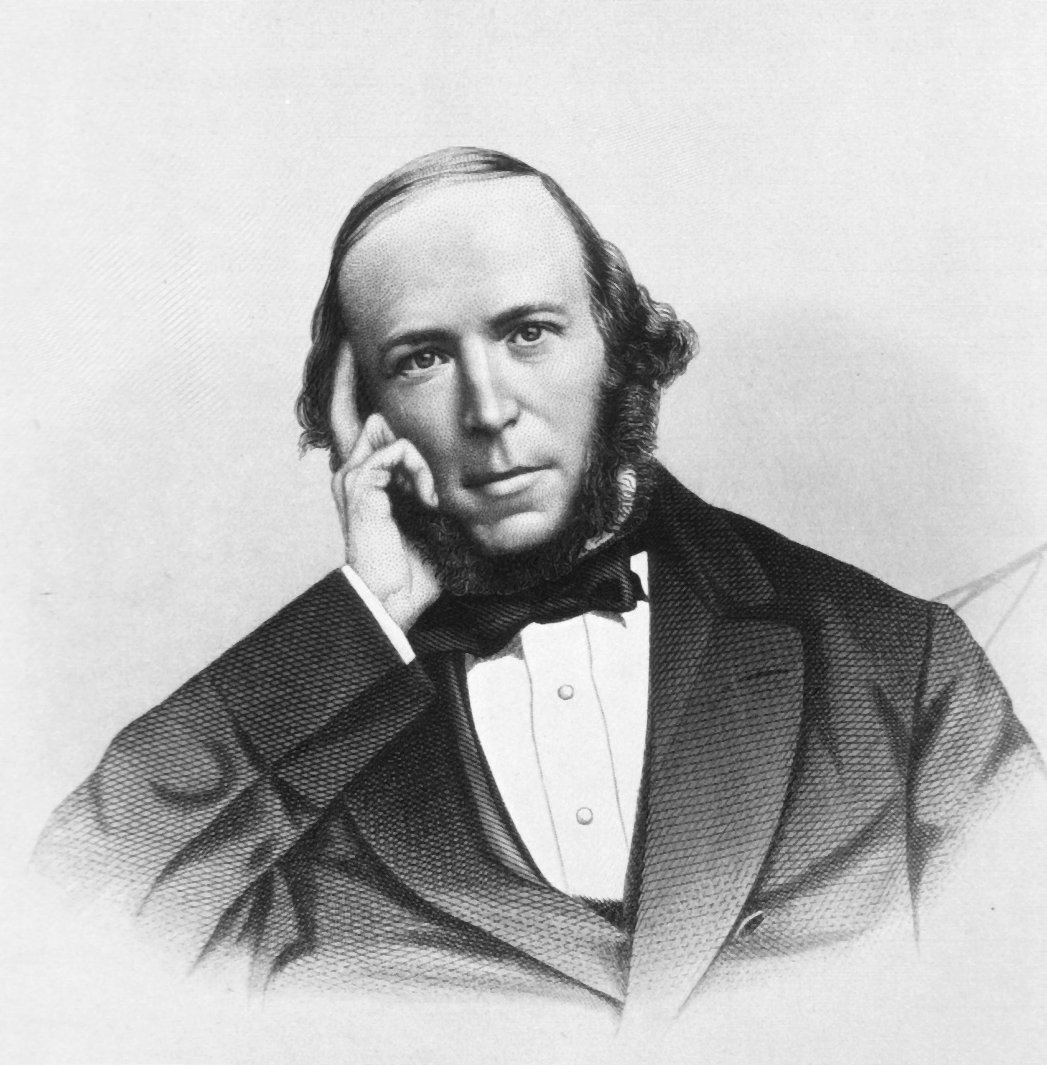

followers of Herbert Spencer a generation before that. (Explanations of the

views of Moore and Spencer can be found in Wikipedia articles online.3,4)

G.E. Moore (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Herbert Spencer (credit: Wikipedia)

I am

being sarcastic about the sensitivity of Moore and Spencer’s followers, of

course. Both my studies and my experience of the world tell me there are more

than a few of these kinds of sensitive aristocrats roving around in today’s

world, in every land (the neocons of the West?). We underestimate them at our

peril. The worst among them don’t like democracy. They yearn to be in charge,

they have the brains to secure positions of authority, and they have the

capacity for lifelong fixation on a single goal. Further, they have the ability

to rationalize their way into truly believing that harsh and duplicitous

measures are sometimes needed to keep order among the ignorant masses—that is, everyone

else.

My conclusion

was that rationalism was far too often a companion of totalitarianism.

The reason did not become clear to me until my thirties, when I learned about

cognitive dissonance and figured the puzzle out. I now see how inclined

toward rationalization other people are and how easily, even insidiously, they

give in to it. On what grounds can we tell ourselves that we are above this

very human weakness? Should we tell ourselves that our minds are somehow more morally aware or more disciplined, and are therefore immune

to such self-delusions? I am aware of no logical grounds for that conclusion about myself or anyone else I have met or whose works I have read.

In

addition, evidence revealing this capacity for rationalization in human minds—some

of the most brilliant of human minds—litters history. How could Pierre Duhem,

the brilliant French philosopher, have written off relativity theory just

because a German proposed it? (In 1905, Einstein was considered, and considered

himself, a German.) How could Martin Heidegger or Werner Heisenberg have

endorsed the Nazis’ propaganda? The Führer principle! German science yet! Ezra

Pound, arguably the best literary mind of his time, on Italian radio defending Fascism. Decent people today recoil and even despair.

George Bernard Shaw (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Jean-Paul

Sartre (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

How

could George Bernard Shaw or Jean-Paul Sartre have become apologists for

Stalinism? So many geniuses and brilliant minds of the academic, scientific,

and artistic realms fell into this trap that one wonders how they could have

made such mistakes in their practical, everyday realm. Once we understand how

cognitive dissonance reduction works, the answer is painfully obvious.

Brilliant thinkers are just as brilliant at self-comforting thinking—namely,

rationalizing—as they are at clear, critical thinking. And the most brilliant

specious terms and fallacious arguments they construct—that is, the most

convincing lies they tell—are the ones they tell themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.