We

can see that most of the laws that have been formulated by scientists do work.

They guide us toward ways of living that get results. Why they work and how

much we can rely on them—i.e. how much we can trust Science—are a lot trickier

to explain.

Now,

while the problems described so far bother philosophers of Science a

great deal, such problems are of little or no interest to the majority of

scientists themselves. They see the law-like statements that they and their

colleagues try to formulate as being testable in only one meaningful way,

namely, by the results shown in replicable experiments done in the lab or in

the field. Thus, when scientists want to talk about what knowing is, they look

for models not in Philosophy, but in the branches of Science that study human

thinking. However, efforts to find proof of empiricism in neurology, for

example, also run into problems.

In

his writings, the early empiricist John Locke basically dodged the problem when

he defined the human mind as a “blank slate” and saw its abilities to perceive

and reason as being due to its two “fountains of knowledge,” sensation and reflection.

Sensation, he said, is made up of current sensory experiences and memories of

past experiences. Reflection is made up of the “ideas … the mind gets by

reflecting on its own operations within itself.” How these kinds of operations

got into human consciousness and what is doing the “reflecting” that he is

talking about, he doesn’t say.5

Modern

empiricists, both philosophers of Science and scientists themselves, don’t care

for their forebears giving in to this kind of mystery-making. Scientists aim to

figure out what the mind is and how it thinks by studying not words but physical

things such as the human genome and what it creates, namely the neurons of the

brain. That is the modern empiricist way, the scientific way.

For

today’s scientists, discussions about what knowing is, no matter how clever, are

not bringing us any closer to understanding what knowing is. In fact, typically

scientists don’t respect discussions about anything we may want to study unless

they are backed with theories or models of the thing being studied, and the

theories are further backed with research conducted on real things in the real

world.

Scientific

research, to qualify as scientific, must also be designed so it can be

replicated by any researcher in any land or era. Otherwise, it’s not credible;

it could be a coincidence, a mistake, wishful thinking, or simply a lie. Thus,

for modern scientists, the analysis of material evidence offers the only route

by which a researcher can come to understand anything, even when the thing she

is studying is what’s happening inside her as she studies.

She

sees a phenomenon in reality, gets an idea about how it works, then designs an

experiment. She tests her theory, then records the results and interprets them.

The aim of her statements is to guide future research onto more fruitful paths

and to build technologies that are increasingly effective at predicting and

manipulating events in the real world. Electro-chemical pathways among the

neurons of the brain, for example can be studied in labs and correlated with

subjects’ perceptions and actions. (The state of research in this field is

described by Donelson Delany in a 2011 article available online and other articles, notably Antti Revonsuo’s in Neural

Correlates of Consciousness: Empirical and Conceptual Questions, edited by

Thomas Metzinger.6,7)

Observable

things are the things science cares about. The philosophers’ talk about what

thinking and knowing are is just that—talk.

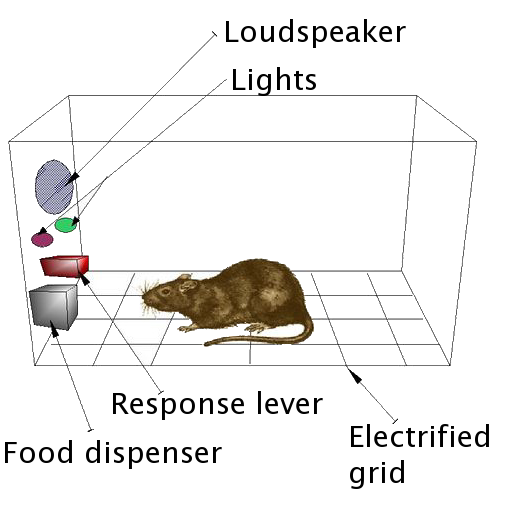

schematic diagram of a Skinner box (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

As

an acceptable alternative to the study of brain structure and chemistry,

scientists interested in thought also study patterns of behaviour in organisms

like rats, pigeons, and people that are stimulated in controlled, replicable

ways. We can, for example, try to train rats to work for wages. This kind of

study is the focus of behavioural psychology. (See William Baum’s 2004 book Understanding Behaviorism.8)

chess playing computer Deep Blue (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

As a

third alternative, we can even try to program computers to do things that are

as similar as possible to the things humans do. Play chess. Knit. Write poetry.

Cook meals. If the computers then behave in humanlike ways, we should be able

to infer some tentative, testable conclusions about what human thinking and

knowing are from the programs that enabled these computers to behave so much like

humans. This kind of research is done in a branch of computer science called Artificial Intelligence or AI.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.