As an acceptable alternative to the study of brain

structure and chemistry, scientists interested in thought also study patterns

of behaviour in organisms like rats, pigeons, and people that are stimulated in

controlled, replicable ways. We can, for example, try to train rats to work for

wages. This kind of study is the focus of behavioural psychology. (See William Baum’s

2004 book Understanding Behaviorism.8)

As a third alternative, we can even try to program

computers to do things that are as similar as possible to the things humans do.

Play chess. Knit. Write poetry. Cook meals. If the computers then behave in

humanlike ways, we should be able to infer some tentative, testable conclusions

about what human thinking and knowing are from the programs that enabled these

computers to behave so much like humans. This kind of research is done in a

branch of computer science called Artificial Intelligence or AI.

To many empiricist philosophers and scientists, AI

seems to offer the best hope of defining, once and for all, a base for their

way of thinking that can explain all of human thinking’s abstract processes and

that is also materially observable. A program either runs or it doesn’t, and

every line in it can be examined. If we could write a program that made a computer

imitate human conversation so well that we couldn’t tell which was the computer

responding and which was the human, we would have encoded what thinking is.

With the rise of AI, scientists felt that they had a beginning point beyond the

challenges of the critics of empiricism with their endless counterexamples. (A

layman’s view on how AI is faring can be found in Thomas Meltzer’s article in The Guardian, 17/4/2012.9)

Testability and replicability of the tests, I

repeat, are the characteristics of modern empiricism and of all Science. All

else, to modern empiricists, has as much reality and as much reliability to it

as creatures in a fantasy novel … amusing daydreams, nothing more.

Kurt Gödel (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

For years, the most optimistic of the empiricists

were looking to AI for models of thinking that would work in the real world.

Their position has been cut down in several ways since those early days. What

exploded it for many was the proof found by Kurt Gödel, Einstein’s companion

during his lunch hour walks at Princeton. Gödel showed that no rigorous system

of symbols for expressing the most basic of human thinking routines can be a

complete system. (In Gödel’s proof, the ideas he analyzed were

basic axioms in arithmetic.) Gödel’s

proof is difficult for laypersons to follow, but non-mathematicians don’t need

to be able to do that formal logic in order to grasp what his proof implies

about everyday thinking. (See Hofstadter for an accessible critique of Gödel.10)

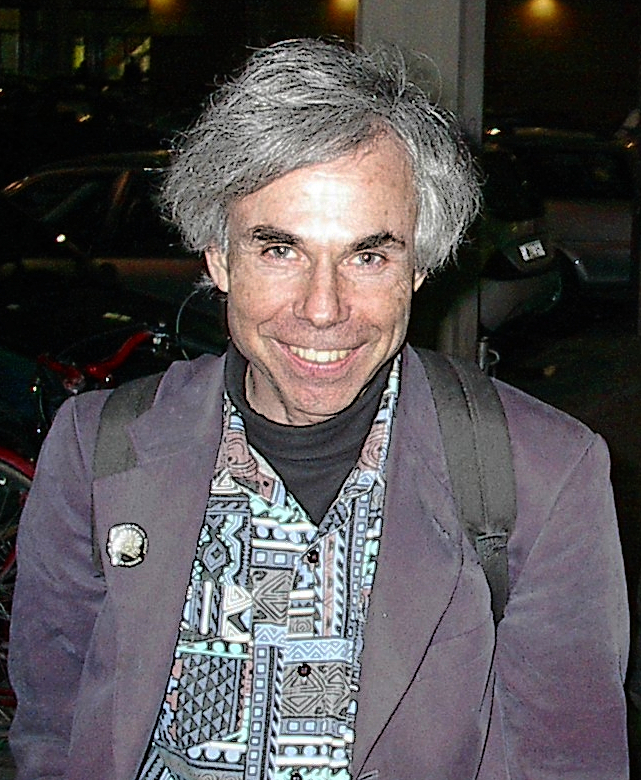

Douglas Hofstadter (credit: Wikipedia)

If we take what it says about arithmetic and extend

that finding to all kinds of human thinking, Gödel’s proof says no symbol

system exists for expressing our thoughts that will ever be good enough to allow

us to express and discuss all the new ideas human minds can dream up.

Furthermore, in principle, there can’t ever be any such system. In short, what

a human programmer does is not programmable.

What Gödel’s proof suggests is that no way of modelling the human mind

will ever adequately explain what it does. Not in English, Logic, French,

Russian, Chinese, Java, C++, or Martian. We will always be able to generate

thoughts, questions, and statements that we can’t express in any one symbol

system. If we find a system that can be used to encode some of our favorite

ideas really well, we only discover that no matter how well the system is

designed, no matter how large or subtle it is, we have other thoughts that we

can’t express at all in that system. Yet we have to make statements that at

least attempt, more or less adequately, to communicate our ideas. Science, like

most human endeavors, is social. It has to be shared in order to advance.

Other theorems in Computer Science offer support for

Gödel’s theorem. For example, in the early days of the development of

computers, programmers were continually creating programs with loops in them.

After a program had been written, when it was run it would sometimes become

stuck in a subroutine that would repeat a sequence of steps from, say, line 79

to line 511 then back to line 79, again and again. Whenever a program contained

this kind of flaw, a human being had to stop the computer, go over the program,

find why the loop was occurring, then either rewrite the loop or write around

it. The work was frustrating and time consuming.

Soon, a few programmers got the idea of writing a

kind of meta-program they hoped would act as a check. It would scan other

programs, find their loops, and fix them, or at least point them out to

programmers so they could be fixed. The programmers knew that writing a

"check" program would be difficult, but once it was written, it would

save many people a great deal of time.

However, progress on the

writing of this check program met with problem after problem. Eventually, Alan

Turing published a proof showing that writing a check program was not possible.

A foolproof algorithm for finding loops in other algorithms is, in

principle, not possible. (See “Halting Problem” in Wikipedia.11) This

finding in Computer Science, the science many people see as our bridge between

the abstractness of thinking and the concreteness of material reality, is Gödel

all over again. It confirms our deepest feelings about empiricism. It is

doomed to remain incomplete.

The possibilities for

arguments and counter-arguments on this topic are fascinating, but for our

purposes in trying to find a base for a philosophical system and a moral code,

the conclusion is much simpler. The more we study both the theoretical points

and the real-world evidence, including evidence from Science itself, the more

we’re driven to conclude that the empiricist way of seeing or understanding

what thinking and knowing are will probably never be able to explain itself.

Empiricism’s own methods have ruled out the possibility of an unshakable

empiricist beginning point for epistemology. (What is the meaning of the word

"meaning"?)

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.