Doberman Pinscher (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

In a more scientific example of Bayesianism working in my own thinking, I will also mention

our Doberman Pinscher–cross pup. Rex was basically a good dog, but he was a

mutt, a Doberman cross we acquired because one of my aunts could not keep him.

People often remarked that he looked like a Doberman, but his tail was not

bobbed. This got me curious. When I learned that most Dobermans had had their

tails bobbed for many generations, I wondered why the tails, after so many

generations of bobbing, had not simply become shortened at birth. I asked a Biology

teacher at my high school, but his answer only confused me. Actually, I don’t think

he understood the crucial features of Darwinian evolution theory himself.

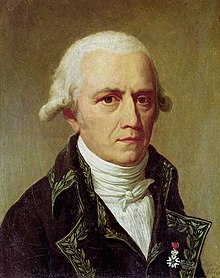

Jean-Batiste Lamarck

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Once I got to university, I took several Biology courses. Gradually at first, and then in a breakthrough of

understanding, I came to realize that I had been thinking in terms of the model

of evolution called Lamarckism. At

first I did not want to let go of this cherished opinion of mine. I had always thought

of myself as progressive, modern, scientific; I did not believe in creationism.

I thought I knew how evolution worked and that I was using an accurate

understanding of it in all of my thinking. It was only after I had read more

and seen by experience that bobbing dogs’ tails did not cause their pups’ tails

to be any shorter that I came to a full understanding of Darwinian evolution.

Evolution for all species proceeds by the combined

processes of genetic variation and natural selection. It doesn’t matter how

often the anatomies of already existing members of a species are altered; if

their gene pool doesn’t change, the next generation will, at birth, basically

look pretty much like their parents did at

birth. Chopping off a dog’s tail doesn’t change the genes it carries in the

sex cells that govern how long the pups’ tails will be. Under Lamarckism, by

contrast, an animal’s genes are pictured as changing because the animal’s body

has been injured or stressed in some way. Lamarckism says a chimp, for

instance, will pass genes for larger arm muscles on to its young if the parent

chimp has had to use its arm muscles a lot.

But Darwinian evolution gives us what we now see as

a far more useful picture. In nature, individuals within a species that are no

longer well camouflaged in the changing flora of their environment, for

example, become easy prey for predators and so they never survive long enough

to have babies of their own. Or ones that are unable to adapt to a cooling

climate die young or reproduce less efficiently, while their thicker-coated,

stronger, smarter, or better camouflaged cousins flourish.

Then, over generations, the gene pool of the local

community of that species does change. It contains more genes for short,

climbing legs or long, running legs or short tails or long tails or whatever

the local environment is now paying a premium for. Gradually, the anatomy of

the average species member changes. If short-tailed members have been surviving

better for the last sixty generations and long-tailed members have been dying

young, before they could reproduce, the gene pool changes. Eventually, as a

consequence, there will be many more individuals with the shorter tail that has

now become a normal trait of the species.

Pondering Rex’s case helped me to absorb Darwinism.

My understanding grew and then, one day, through a mental leap, I suddenly “got”

the newer, better model. A model I hadn’t understood suddenly became clear, and

it gave a deeper coherence to all of my ideas and observations about living

things. For me, Lamarckism became just an interesting footnote in the history

of Science, sometimes still useful because it showed me one way in which my

thinking, and that of others, could go wrong.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.