The logical flaws that can be found in

empiricist reasoning aren’t small ones.

Even the terms used in scientific law statements

are vulnerable to attack by the skeptics. Hume argued more than two hundred

years ago that we humans can’t know for certain that any of the laws we think we

see in nature are true because when we state a natural law, the terms we use to

name the objects and events we want to focus on exist only in our minds.

A

simple statement that seems to us to make sense, like the one that says hot

objects will cause us pain if we touch them, can’t be trusted in any ultimate

sense. To assume this “law” is true is to assume that our definitions for the

terms hot and pain will still make sense in the future. But we can’t know that.

We haven’t seen the future. Maybe, one day, people won’t feel pain.

Thus, all the terms in natural law statements, even

terms like galaxy, proton, atom, acid, gene, cell, and so on, are fabrications of our minds, created because

they help us to sort and categorize sensory experiences and memories of those

experiences and talk to one another about what seems to be going on around us.

But reality does not contain things that somehow naturally fit terms like “atom”,

“cell”, or “galaxy”. If you look at a gene, it won’t be wearing a name tag that

reads “Gene.”

In other languages, there are other terms, some of which overlap in the minds of the speakers of that language with things that English has a separate word for entirely. (In Somali a gene is called “hiddo”.) We divide up and label our memories of what we see of reality in whatever ways have worked fairly reliably for us and our ancestors in the past. And even very simple things are seen in ways determined by what we've been taught by our mentors. In English, we have seven words for the colors of the visible spectrum or, if you prefer, the rainbow; in some languages, there are as few as four.

Right from the start, our natural law statements

must gamble on the future validity of our current mental categories—that is, our

human-invented terms for things. The terms can seem solid, but they are still

gambles, and some terms humans once gambled on with great confidence turned out

later, in light of new evidence, to be naïve and inadequate.

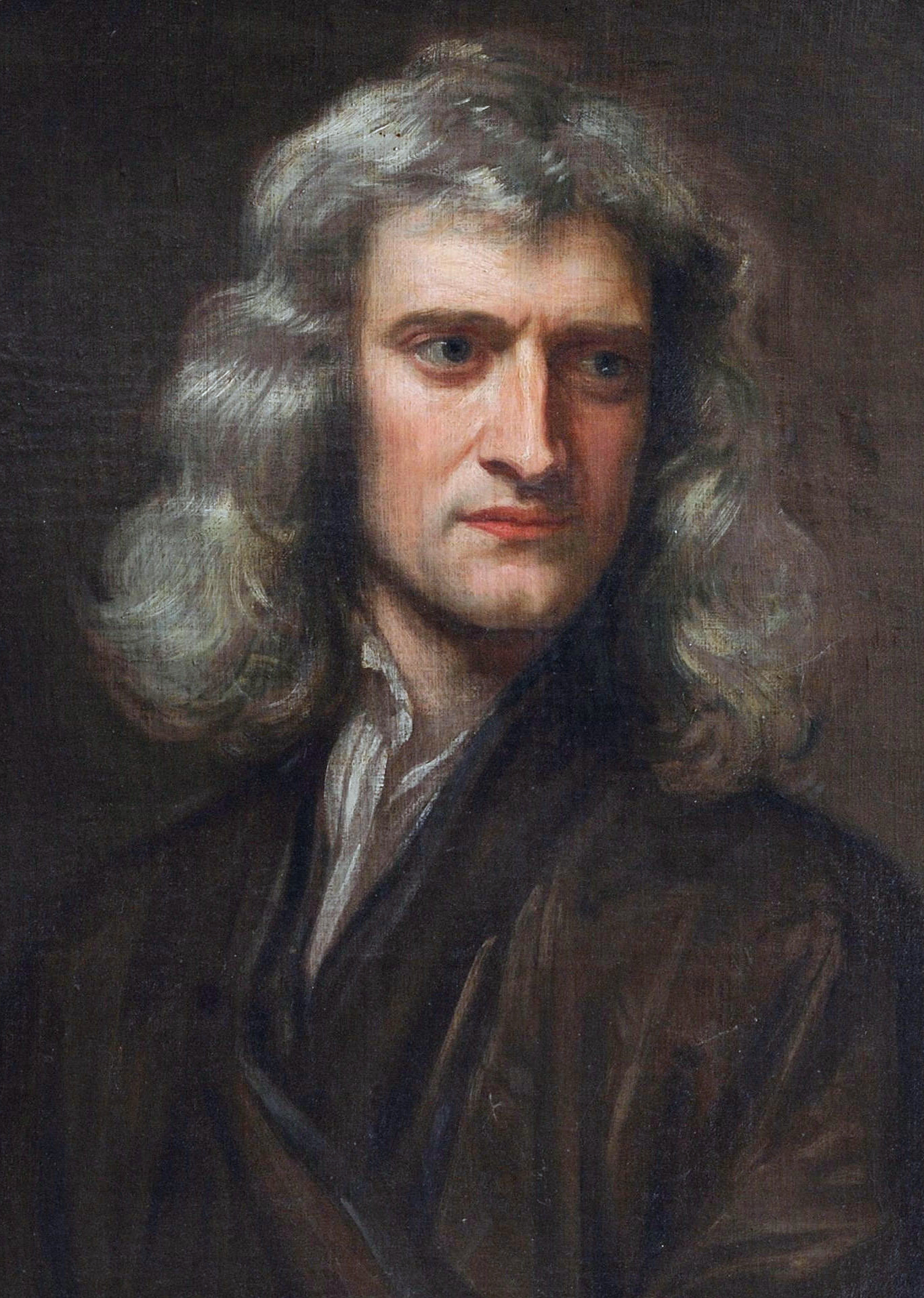

Isaac Newton (artist:

Godfrey Kneller) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Isaac Newton’s laws of motion are now seen by physicists

as being useful, low-level approximations of the subtler, relativistic laws of

motion formulated by Einstein. The substance called phlogiston once seemed to explain all of chemistry. Then Antoine Lavoisier

did some experiments showing phlogiston didn’t exist. On the other hand, people

spoke of genes long before microscopes that could reveal them to the human eye

were invented, and people still speak of atoms, even though nobody has ever

seen one. Some terms last because they enable us to build mental models and do

experiments that get the results we predicted. For now. But the list of

scientific theories that eventually “fell from fashion” is very long.

Antoine Lavoisier (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.