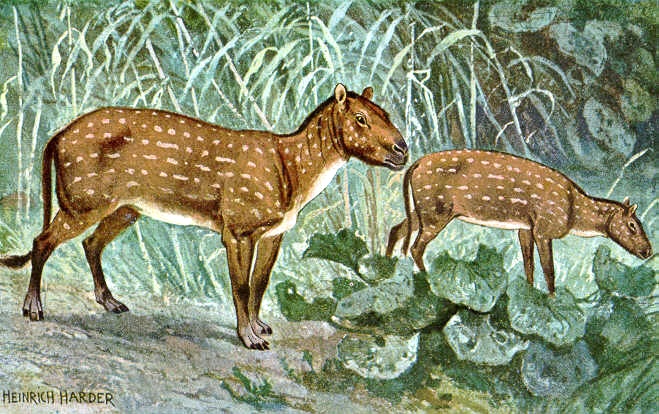

Eohippus (artist's conception)

(By Heinrich Harder [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Do we, in our endlessly subtle rationalizations, see

what is not there? Not really. A fairer way of describing this dissonnance-reducing tendency in human minds is to say that out of the billions of sense details, the

googols of patterns we might see among them, and the infinite interpretations

we might give to those details, we tend to give prominence to those that are

consistent with the view of ourselves that we find most psychologically comforting. We don’t like seeing ourselves as hypocrites. We don’t like nagging

feelings of cognitive dissonance. Therefore, we tend to be drawn to ways of thinking,

speaking, and acting that reduce that dissonance, especially in our internal

pictures of ourselves. In short, inside our heads, we need to like ourselves.

There

is nothing really profound being stated so far. But when we come to applying

this theory to philosophies, the implications are a little startling.

Other than rationalizations, the rationalists have

nothing to offer.

What are Plato’s ideal “forms”? Can I measure one?

Weigh it? If I claim to know the forms and you claim to know them, how might we

figure out whether the forms you know are the same ones I know? If, in a

perfect dimension somewhere, there is a form of a perfect horse, what were creatures

called eohippus and mesohippus (biological ancestors of the horse), who were

horsing around long before anything Plato could have recognized as a horse

existed?

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.