In life, examples of the workings of Bayesianism

can be seen all the time. All we have to do is look closely at how we and the

people around us make up, or change, our minds about our beliefs.

When I was in junior high school, each year in June

I and all the other students of the school were bussed to the all-city track

meet at a stadium in West Edmonton. Student athletes from all the major junior

high schools in the city came to compete in the biggest track meet of the year.

Its being held near the end of the school year, of course, added to the

excitement of the day.

A few of the athletes competing came from a special

school that educated and cared for those kids who today would be called

mentally challenged. In my Grade 9 year, three of my friends and I, on a patch

of grass beside the bleachers, did a mock cheer in which we shouted the name of

this school in a short rhyming chant, attempted some clumsy chorus-line kicks

in step, crashed into each other, and fell down. I should make clear that I did

not learn such a cruel attitude from my home. My parents would have been

appalled. But fourteen-year-olds, especially among their peers, can be cruel.

The problem was that one of the prettiest and

smartest girls in my Grade 9 class, Anne, was sitting in the bleachers,

watching field events in a lull between track events. She and two of her

friends happened to catch our little routine. By the glares on their faces, I

could see they were not amused. Later that day I learned that although she had

an older brother who had attended our school and done well academically, she

also had a younger brother who was a Down syndrome child.

I apologized lamely the next day at school, but it

was clear I’d lost all chance with her. However, she said one thing that stayed

with me. She told me that if you form a bond with a mentally retarded person (retarded was still the word we used in

those days), you will soon realize you have made a friend whose loyalty, once

won, is unchanging and unshakeable—probably, the most loyal friend you will

ever have. And that realization will change you.

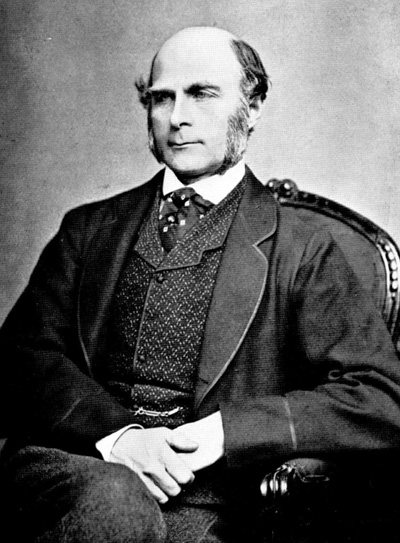

Francis Galton, originator

of eugenics (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

It was the proverbial thin edge of the wedge.

Earlier, I had absorbed some of the ideas of the pseudo-science called eugenics from one of my friends at

school, and I had concluded the mentally challenged added nothing of value to

the community but inevitably took a great deal out of the community. What Anne

said made me begin to question those assumptions.

Over years of seeing movies like A Child Is Waiting and Charlie and of being exposed to awareness-raising

campaigns by families of the mentally challenged, I began to see them in a

different light. Over the decades, they came to be called mentally handicapped and then mentally

challenged or special needs, and

the changing terminology did matter. It changed our thinking.

I became a teacher, and then, in the middle of my

career, mentally challenged kids began to be integrated into the public school

where I taught. I saw with increasing clarity what they could teach the rest of

us, just by being themselves.

Tracy was severely handicapped, in multiple ways,

mentally and physically. Trish, on the other hand, was a reasonably bright girl

who had rage issues. She beat up other girls, she stole, she skipped classes, she

smoked pot behind the school. But when Tracy came to us, Trish proved in a few

weeks to be the best with Tracy of any of the students in the school. Her

attentiveness and gentleness were humbling to see. In Tracy, Trish found

someone who needed her, and for Trish, it changed everything. As I watched them

together one day, it changed me. Years of persuasion and experience, by gradual

degrees, finally, got to me. I saw a new order in the community in which I

lived, a new view of inclusiveness that gave coherence to years of observations

and memories.

Today, I believe the mentally challenged are just

people. But it was only grudgingly at fourteen that I began to re-examine my

beliefs about them. At fourteen, I liked believing that my mind was made up on

every issue. Only years of gradually growing awareness led me to change my

view. A new thinking model, gradually, by accumulation of evidence, came to

look more correct and useful to me than the old model. Then, in a kind of

conversion experience, I switched models. Of course, by gradual degrees,

through exposure to reasonable arguments and real experiences, I and a lot of

other people have come a long way on this issue from what we believed in 1964.

Humans can change.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.