Chapter 4 – Foundations for a Moral Code:

Rationalism and Its Flaws

In Western philosophy, rationalism is the main alternative to empiricism for describing

the human mind and for modeling what knowing is. It is the way of Plato in

Classical Greek times and of Descartes in the Enlightenment. Rationalism claims

that the human mind can build a system for understanding itself and for how it

knows its universe only if that system is first of all grounded in the human

mind by itself, before any sensory experiences or memories of them enter

the thinking system.

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

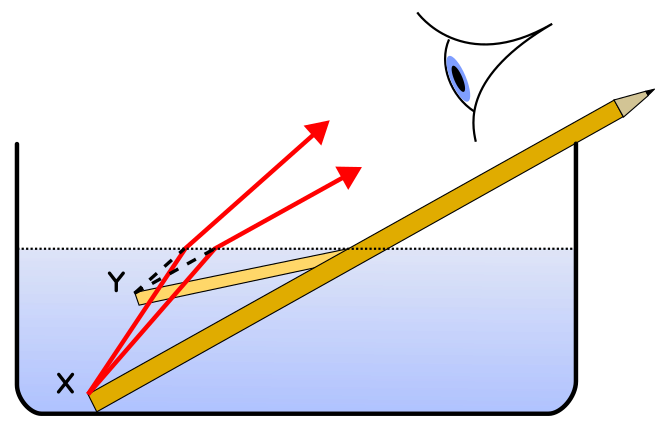

Descartes, for example, points out that our senses give

us information that can easily be faulty. As was noted above, the stick in the

pond looks bent at the water line, but if we remove it, we see it is straight.

The hand on the pocket warmer and the hand in the snow can both be immersed shortly

after in tepid tap water; to one hand, the tap water is cold and to the other,

it is warm. And these are the simple examples. Life contains many much more

difficult ones. Therefore, the rationalists say, if we want to think about

thinking in rigorously logical ways, we must try to construct a system for

modelling human thinking by beginning from some concepts that are built into

the mind itself before any unreliable sense data or memories of sense data even

enter the picture.

Plato says we come into the world at birth already

dimly knowing some perfect “forms” that we then use to organize our thoughts.

He drew the conclusion that these useful forms, which enable us to make sense

of our world, are imperfect copies of the perfect forms that exist in a perfect

dimension of pure thought, before birth, beyond matter, space, and time—a

dimension of pure ideas. The material world and the things in it are only poor

copies of that other world of pure forms ultimately derived from the pure Good.

The whole point of our existence, for Plato, is to discipline the mind by study

until we learn to more clearly recall, understand, and live by the perfect

forms—perfect tools, perfect cooking, perfect medicine, perfect beauty, perfect

justice, perfect tools, perfect animals, and many others.

Descartes formulated a similar system of thought that

begins from the truth the mind finds inside itself when it carefully and

quietly contemplates just itself. During this quiet and totally concentrated

self-contemplation, the thing that is most deeply you, namely your mind,

realizes that whatever else you may be mistaken about, you can’t be mistaken

about the fact that you exist; you must

exist in some way in some dimension in order for you to be thinking about

whether you exist. For Descartes, this was a starting point that enabled him to

build a whole system of thinking and knowing that sets up two realms: a realm

of things the mind deals with through the physical body attached to it, and

another realm the mind deals with by pure thinking, a realm built on the “clear

and distinct ideas” (Descartes’s words) that the mind knows before it ever

takes in the impressions coming from the physical senses.

These

two rationalists have had millions of followers—in Descartes’s case for four

hundred years and in Plato’s case for well over two thousand. They have

attacked empiricism for as long as it has been around (since the 1700s, or in a

simpler form, some argue, since the time of Aristotle, who was Plato’s pupil,

but who disagreed diametrically with Plato on several matters).

The debate between the rationalists and the

empiricists has not let up, even in our time. But in our quest to find a

universal moral code, we will find that we must discard rationalism just as we

did empiricism; rationalism contains a flaw worse than any of empiricism’s

flaws.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.