Chapter 14 The

War Digression

Ruins of ancient Beit She’an

(credit: James Emery, via Wikimedia Commons)

This chapter contains a painful, but necessary, digression. But first

let’s again briefly review the whole case so far for our overall argument.

Every society, prehistoric, historical, and contemporary, must have a

moral code by which its citizens can run their lives. Societies also have

always tried to integrate their values systems with their understanding of physical

reality.

A society’s way of seeing reality, i.e. its worldview, is crucial to its

staying in a favorable part of the environment around it. Guided by their

worldview, the folk decide where the crops, animals, etc. should be placed,

what provision to make against famines, plagues, etc.. A society’s worldview

informs its values. Then, the values shape the tribe’s behavior patterns which then

profoundly influence the odds that the tribe will survive. Humans always try to

live in ways that are consistent with their model of reality, i.e. their

worldview.

A worldview is a way of understanding the physical world. It is a way of

bringing order to sense data – the things we see, hear, etc. – and our memories

of sense data. Every society that survives comes, by consensus of generations

of its people, to a way of organizing perceptions of the world and of people’s

roles in that world. Their worldview controls what they notice and what they miss

in their surroundings. The people then are programmed to think of their worldview

and way of life as being natural – just humans being human.

Worldviews and the value systems and morés that go with them are subtly

interdependent. Every change in a society’s worldview leads to values shifts,

and values shifts lead to changes in the behaviors of the folk. Concepts,

values, and behaviors all interact in a complex. Changes in a tribe’s worldview

lead to changes in its concepts and values and, subsequently, to its ways of

talking and acting, i.e. its culture. Re-write the code; change the actions.

For example, if a tribe discovers that a new fruit just come into their

area is edible and tasty, they may explain this piece of luck as a gift from

one of their gods. The phenomenon will even be seen as proof that this god does

love them. Holding a festival and gathering his fruit is …just logical. If the

tribe comes to believe diseases are caused by breathing the vapors near an evil

god’s swamp, tribe members will steer widely away from that swamp from then on.

And these are simple features of a tribe’s worldview. Worldviews, and

the behaviors they cause, get much more complex in the histories of real

tribes.

Aztec calendar (a graphic of a worldview)

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Thus, a society’s worldview, if it is analyzed closely, can be seen as a

condensed guide to that society’s values. In conjunction with their basic view

of how the world works, a tribe’s people, by trial and error, arrive over many

generations at a system of values and behaviors that they teach to their young

as being right. The word right has two meanings here: right

as in “accurate in the physical world” (Is that thermometer right?) and right

as in “morally correct” (Do the right thing.).

However, when we closely analyze this ambiguity, we see that it is not really

ambiguous at all. We long deeply to feel that our idea of “moral” is consistent

with reality. We long to believe that our idea of right (good) is right

(accurate).

Worldviews, concepts, values, and behaviors are all interacting and

evolving all the time in every society’s culture. This is the gist of our

argument so far.

And now, a digression. It is an important digression that has been

lingering at the edge of our argument for several chapters. I must deal with

it.

If we aim to be rigorously logical at this point, we can also become very

discouraged. Even a little investigation into History tells us that every

society has its own worldview, values, and morés (accepted patterns of

behavior): its culture. The natural trend for every human society is to keep

moving ahead with its way of life while simultaneously diverging from, and

becoming more and more alien to, all other societies.

Does an analysis of human values systems imply that we can’t ever arrive

at a set of values that would work for all humans? Will the people in the

world’s many different tribes continue to be driven by incompatible sets of

values? Even worse, will citizens of the world’s societies continue to follow

their own values so devoutly that the folk in each will tolerate no other way

and will feel hostile toward other folk whose values and behaviors differ from

their own? A study of History tells us that we first suspect, then fear, then

hate “others”.

Analyzing the physical environment in which all societies evolve adds to

our feelings of hopelessness. The environment around us is always changing so

our values systems and behaviors adapt to those changes. When new conditions

arise, many different societies’ responses to them may all prove viable. Each

society will have its own “way”. This variety shows how free we are. This has

happened, for example, in the animal world with lions and hyenas.

Lions

and hyenas fight over a kill

(Kruger

Sightings, via Wikimedia Commons)

Lions and hyenas occupy the same habitat and hunt the same prey. Their

relative competitive advantages and disadvantages interact in complex ways, but

they both flourish at the same time in the same habitat.1 In

this, they are akin to human societies, whose basic operating codes are mostly

cultural, rather than genetic, but whose competitive situations are analogous

to those of lions and hyenas. Lions and hyenas exist as hostile neighbors,

drive one another away from kills, and often fight to the

death. Sometimes, lions win, sometimes not. Hyenas are numerous, fight as

packs, and have powerful jaws.

Examples of human societies like lions and hyenas fill History: Pondo/Zulu, English/French, Apache/Pueblo, Iroquois/Huron,

Croat/Serb, Han/Mongol, Ghiljai/Durrani, Ukrainian/Pole, Sunni/Shia, etc.,

etc.).

In other words, the evidence indicates that wars between societies come

about naturally. Different, often neighboring societies – each with its own

values and customs – arise, diverge, become mutually hostile, and make war on

each other as naturally as the world turns. Such has been the case for all of

human history so far. Cultural competition is the human form of species

competition.

So, is war inevitable? The evidence of History seems to answer with a

firm “yes”. Wars are fought over these very differences. Following this reasoning,

we see what Hitler thought of as his great insight: he accepted that war was an

inevitable, periodic test of the cultural and (he said) “racial” fitness of every

nation. He ranted his worldview to his last hour. To geneticists, his “racial”

theories are meaningless silliness. “Race” is a myth. We humans are all one

species. But when his worldview is extended to an analysis of cultural

groupings of humans (e.g. tribes, societies, and nations) – and the conflicts

among them – it becomes more

disturbing.

The

consequences of war: ruins of Nuremberg, Germany, 1945.

(credit: Keystone/Second

Roberts, via Wikimedia Commons)

The ancient Greeks had two words for humans: Hellenes (themselves)

and barbarians (everyone else). Similar in view and vocabulary are

the Chinese. To many Chinese in China, I would be gwai lo, an evil

alien. The word Masai – a famed African tribe’s name for itself

– means people, as do the words Innu in Innu and Cheyenne

in Cheyenne. For hundreds of years, Europeans divided the members of the

species homo sapiens into Christians and heathens. The Muslims

speak of the faithful and the infidel. Jews were proud they were not Gentiles.

Tutsis were not Hutus. In short, people in all these cultures believed they

were the only fully human humans. Thus, wars keep coming, everywhere.

The evidence mounts on all sides against the hopes of those who love

peace. People find it easy, even moral, to attack, conquer, assimilate, sometimes

even exterminate other humans whom they regard as members of an inferior

subspecies. By this reasoning, Hitler was only exhorting the Germans to accept

the inevitability of war and get to work at being winners.

By this reasoning, we see that war is the way by which we have become

our own predators. In the animal world, as a species falls out of step with its

environment, it dies out. Starvation, disease, inability to reproduce, a

rapidly acquired vulnerability to predators – any of these can wipe out a

species. In humans, it is ineffective

parts of our species’ concepts-values-behaviors pool – its meme pool, rather than

its gene pool – that are cut out by war.

Note that we are different in this from other species. Wars mainly kill

the young and fit – prime breeding stock. Wars don’t serve a genetic mode of

evolution anymore, if they ever did. They certainly haven’t since the first

technological war, i.e. the US Civil War. In modern wars, too many young men

die; too much prime breeding stock is lost for anyone to claim that wars are

part of the biological process of evolution. But wars do serve the cultural mode

of evolution. Wars test, re-write, and sometimes eliminate, cultures.

Gandhi (South Africa, 1906) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

For thousands of years, we have evolved culturally by this ugly means. For

centuries, no other species and no change in our environment has been able to

seriously shake us. We even save individuals born with genetically transmitted

defects that in any other species would be fatal. These individuals live and go

on to reproduce. Therefore, we aren’t evolving genetically; if anything, we are

genetically devolving. But we are evolving culturally.

We prey on ourselves, not eating corpses, but killing followers of other

cultures, if they don’t kill us first. Eventually, fitter cultures win. By this

means, we cut out parts of our species’ meme pool whose usefulness is fading.

This system has worked brutally, but efficiently, for a long time. Evidence

that it worked lies, for example, in the way in which, within a generation of

being conquered, most people subjugated under the Romans were effectively

“Romanized”. Rome had a more efficient culture than did any of the lands it

conquered – a culture that swallowed up neighboring tribes, their territories,

and ways of life. Similar cases fill history. For centuries, war worked.

Today, however, war has made itself obsolete. Our weapons have grown too

big. Our species very likely would not survive a World War III. Combining what

we know from History, and our war habit, with what we know of our present

technology leads us to envision, in not very long, a worldwide bloom of

mushroom clouds, followed within a decade by images of our once beautiful, blue

planet, burned bare and wrapped in clouds of radioactive smoke and ash.

On the other hand, we have to evolve. If we ever give up war, will we

devolve culturally, grow sickly, then die out like a herd of deer that has no

predators because it’s isolated on an island? Experts have said so. War, they

insist, is ugly but necessary. They’re ready to risk nuclear holocaust, even

initiate it.2

However, there is evidence to support the belief that humans may learn

to live, multiply, and spread – that is, to remain vigorous – without

constantly killing one another. The strongest evidence lies in how, in every

society, there are some people who seek to settle apparently irreconcilable

differences by negotiation rather than by violence. Some people can stick to

the ways of Reason even when they're being attacked physically.

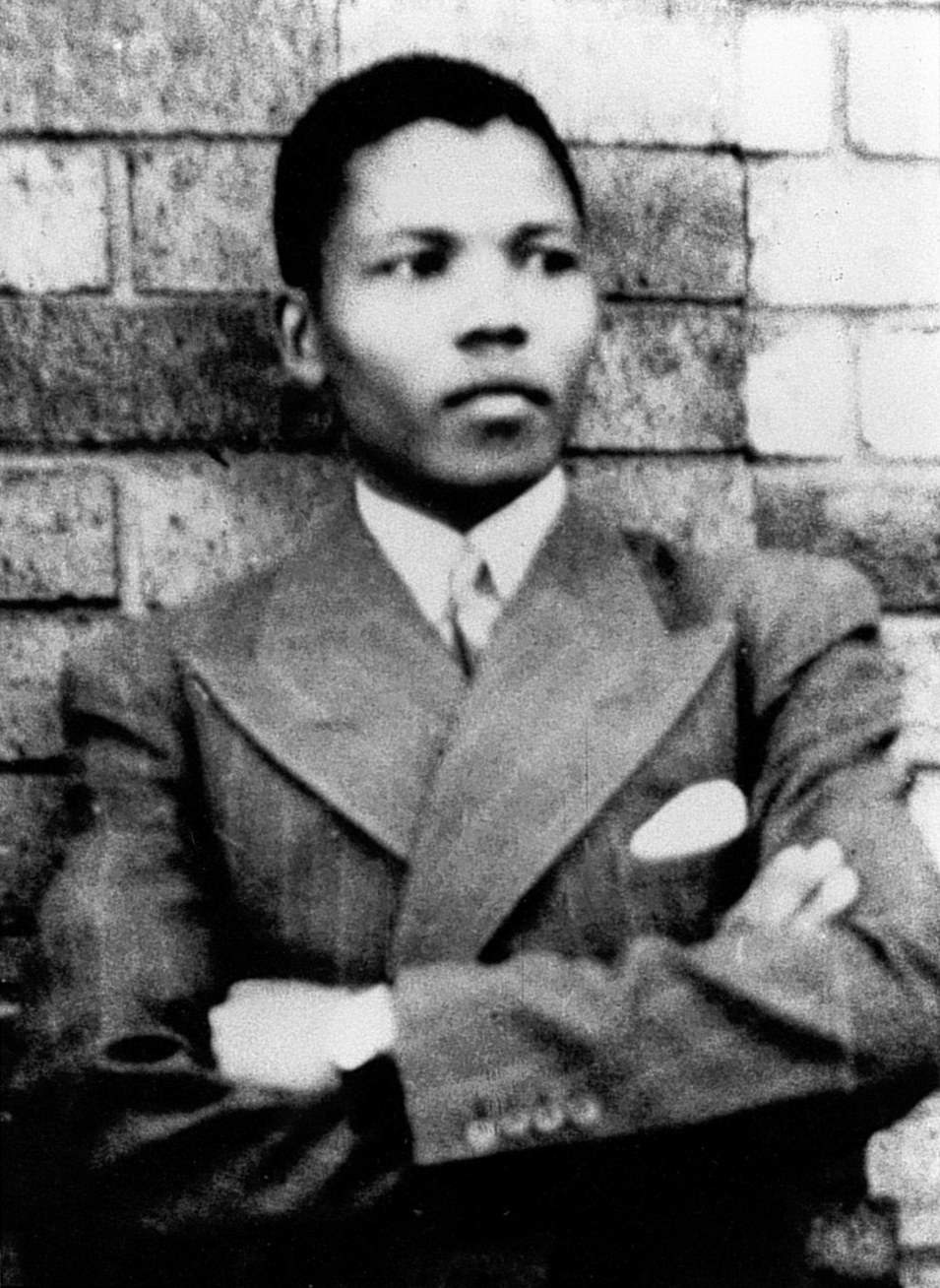

Nelson Mandela (1937)

(credit: author unknown, via Wikimedia Commons)

They are acknowledging implicitly that they do not believe any single

set of values or worldviews – even the ones they learned as children – is the

only “right” one. From a social sciences viewpoint, these peaceful members of

society follow a values system that puts the lives of other humans ahead of any

anxieties they experience when they see other humans living in ways that seem

alien to them.

Martin

Luther King, Jr. (credit: Dick DeMarsico, via Wikimedia Commons)

Another bit of evidence supporting the hypothesis that reason can be

stronger than prejudice is the vigor evident in pluralistic societies, ones

that have succeeded in integrating several cultures. A nation formed by merging

many ways of life can work. Britain is an example. There Celts, Iberians,

Romans, Angles, Saxons, Danes, Normans, and, recently, folk from all the countries

of Britain’s former empire have blended. Folk who call themselves “British” today

show physical and cultural traits from lands all over the globe.

Furthermore, we can see that, after a war, living patterns and values

change in major, radical ways not only for the vanquished, but often for the

victors as well – ways not anticipated by the planners on either side.

When I was a boy in the 1950s in Edmonton, Alberta, there were two

German delicatessens in my city, and “dojo” was just a word in a few novels.

By time I was a young man, delicatessens and karate dojos could be found all

over my city, a city whose men had recently won a war against Germany and

Japan.

Today, Germany and Japan are two of the strongest economies in the

world, and Edmonton schools contain students from almost every culture on

earth. In retrospect, it seems stupid that 55,000,000 people had to die so the

Japanese could learn to open up to the ways of the gaijin, and I

could learn to love and trust people named “Kobayashi”. We in the West were the

victors in that war, yet today we embrace many of the morés of the vanquished.

All of this evidence says clearly that we can integrate. The trick in

the future will be to bring about these changes on both sides of every rivalry

by planned interactions in commerce, sport, science, and art, and then

intermarriage. Peaceful coexistence and reason instead of bloodshed. This will

be hard, but not impossible. In this age of the internet and the global

marketplace, it is getting easier by the day.

One way or another, changes keep happening in every human culture,

whether the changes originate from within or without. But changes in ways of

living aren’t always accompanied by people hurting and killing each other. And

given that in the end we all must answer with our cultural codes and morés to

the same physical reality, there is reason to hope that we could create one

universal culture. Peace-loving people, if they can become wise enough and

motivated enough, may prove fitter for survival than the warmongers.

Peace-mongers will just have to acquire a new, Science-based moral code and

then learn to program it into the world’s children. Teach them to see the

principles of right and wrong in the observable events of physical reality

itself, then, to be both vigorous and respectful of others

and, finally to practice these principles in all their actions every day.

A food custom: Russian pelmeni

(credit: Jorge

Cancela, via Wikimedia Commons)

The evidence says that humans are capable of being open-minded,

creative, and adaptable. From within ourselves, we can add perseverance to this

mix: a constant passion for peace. There is hope. For the memes of decency

hitting critical mass in our species. For the survival of our world. For

us.

A food

custom: Canadian poutine (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

We should note here also that the variety of morés and values of our

societies has led some social scientists and philosophers to claim that every

system of values is correct in its own context, and none is correct in any objective

sense. All moral codes, they claim, are arbitrary. This “postmodernist” view is

a dangerous view to take. These people have the best of intentions: they want

to encourage us all to feel tolerant toward one another and get along.

But their moral code is not assertive enough. If it can be said to aim

at all, it aims to fill the gap left after social scientists, historians, and

philosophers have deconstructed all presently existing moral codes. That task,

like an irrational number, never terminates nor repeats. Modern social science,

with its view of values as arbitrary, leads to moral paralysis. It enables dithering, not action.

Therefore, this postmodernist stance is not good enough. By its

paralysis, it yields the field to the bullies of the world. And the bullies

know what they want. They’ll march straight to it if we let them. This nonsense,

uncorrected, will lead us to WWIII. That option, we have seen, is no longer a

rational one.

A food custom: American hamburger

(credit: Evan-Amos)

A food custom: American hamburger

(credit: Evan-Amos)

Humans need strong, affirmative guidelines to act and live by. What the

moral relativists seem to be aiming to produce is a cynicism that sees itself

as above critique because, in the realm of morals, it affirms nothing and,

thus, can’t be critiqued. But real humans have to make decisions daily in real

life.

We need a global model of what is right, one that has a sense of

direction and purpose and that is grounded in things we can all see. In this

Age of Science, we know the only thing that fits this description is physical

reality itself.

In the analogous situation for scientists themselves, they couldn’t do

research without models and theories to guide them as they planned their

experiments. Without a model to guide research, scientists would be buffoons

wandering through rooms full of computers, gauges, and beakers, with no clue as

to what they were doing there. With no moral code grounded in reality to guide

us in real life, especially in inter-cultural contexts, we become absurd buffoons.

So, let me be blunt: postmodernism leads to the consequence of resigning

this planet over to the bullies. When tolerant citizens can say only what they

are against, but never what they are for or why, the bullies with their “will

to power” (Nietzsche’s and Hitler’s term) will sway the masses and get their

way – by trickery, threats, promises, and consciously, willfully inflicted pain.

The Western Allies in the 1930's did not call themselves postmodernist moral

relativists, but relativist ways of thinking were already loose in the West,

from Nietzsche on. The consequence was that most of the leaders of the nations

that might have stopped Hitler, Mussolini, and Imperial Japan had no stomach

for such action. In fact, many prominent citizens in the West admired the

fascist states and leaders and said so openly. (Even Roosevelt said early on he

was impressed by what Mussolini was doing in Italy.3) The

consequence of these leaders’ confusion was WWII and the deaths of fifty-five

million people. Parallel situations fill the History texts right into our own

time.

Benito

Mussolini (credit: Martianmister, via Wikimedia Commons)

The practical problem for the moral relativists of the West is that,

while they may see morals as being relative, trivial even, other nations are

programming their citizens with the belief that their nation is right,

and thus the further belief that they must spread their culture until it

controls all of this planet. In such states, democracy is seen as a weak,

pathetic delusion for dithering fools.

Aggressive, jingoistic, smug, self-righteous, bully leaders have always

existed. Democracies have to be motivated to face them if we are to have a

world in which we can discuss our options at all.

But relativism paralyzes all motives. We must do better. Careful

reasoning says we can. Not moral relativism, but not jingoistic nationalism

either.

We have to build a more assertive moral code than moral relativism

offers. Furthermore, this code will only be considered acceptable by viable

numbers in today’s world if it integrates our world view – that is Science, our

best model of reality – with the code itself. Then, many cultures will be able

to form and co-exist. Harmonizing them all is what will be required of us if we

are to survive. If we are to live, we must find our way to global democracy.

The task of maximizing our species’ potential by creating a new,

radically democratic culture is daunting. Falling back on traditional,

tribalistic ways of thought is more comforting. But the depth of our anxiety at

the thought of a true global democracy is also an indicator of how free we

humans really are.

We can already see that some values don’t work. In today’s world, with

the weapons we now have, both values that encourage militarism and values that

create moral inertia are not survival oriented. They will bring disaster. We

have to find a third way. Not a return to any of the traditional moral codes,

but not moral relativism either.

Reason is our way out of this dilemma. It could give us a moral code

that all of us could agree on because the code would be grounded in physical evidence

that all of us can see. The way of Science is the way of Reason.

War is not inevitable, any more than ancient morés like rape or

infanticide are, as long as we don't give up on our mission to outwit it and

prevent it.

A universal moral code would not end the diversity of cultures on this

planet; it would simply provide a means by which disputes between cultures

could be settled by negotiation and compromise – without anyone having to go to

war.

Then, by commerce, art, sport, intermarriage, and international law to

handle disputes, the integration of cultures could take place. The theory is

sound. Gradually, nations would cease to be adversaries because, gradually over

generations, they would integrate into one pluralistic, democratic nation.

Artist’s conception of a park area inside a space

station

(credit: Donald Davis, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Now, we can leave the war dilemma and return to building a universal

moral code. Ultimately, creating/writing that code will be our way to live.

We have arrived at the step in our reasoning showing that a society’s

concepts and morés are all intimately connected to its worldview. We have also

dealt with the war digression.

Now we can go back to examining how worldviews of the past shaped the moral

codes – and lives – of real people. Then, when our cultural evolution model is

well established, we’ll use it to explain what our best current worldview –

Science – is implying for us in moral terms. Use Science to guide us to a new

understanding, and a new code, of right.

Notes

1. Layne Cameron, Nora Lewin, “Social Status Has Impact on Overall

Health of Mammals,” Michigan State University Today, March 12,

2015.

http://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2015/social-status-has-impact-on-overall-health-of-mammals/?utm_source=weekly-newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=standard-promo&utm_content=image.

2. Dr. Stephen J. Cimbala, “War-Fighting Deterrence: Forces and

Doctrines in U.S. Policy,” Air & Space Power Journal (May–June,

1983).

http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/aureview/1983/may-jun/cimbala.htm.

3. “Benito

Mussolini,” Wikiquote, the Free Quote Compendium. Accessed

April 21, 2015. http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Benito_Mussolini.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.