Chapter 16

Worldviews since The

Renaissance

Renaissance-era watch

(credit:

Melanchthon's watch, Wikimedia Commons)

Renaissance society arose out of ideas that melded respect for the

individual and exaltation in his creative potential with respect for abstract

thinking and respect for practical results. Science requires all these if it is

to flourish.

The resulting hybrid, Renaissance culture, valued people who could be

pious, moral, and contemplative while also being creative,

practical, and original all at the same time. They called such a person a

"Renaissance man”. The ideas of Greece, Rome, and Christianity

had blended in a way that was coherent and effective. The new worldview worked.

It got results. New printing presses made books affordable, and Renaissance

ideas began to spread across Europe.

The growing Renaissance focus on the rights of the individual produced

some excesses (e.g. the Thirty Years’ War) as those who sought change fought

those who sought stability. But the excesses were gradually tamed. The melding

of ideas and morés reached equilibrium. When the dust settled, one thing was

clear: there would be no going back to Medieval ways of thinking. The way

forward was to live by Reason, or more accurately, the best works of Reason’s

darling child, Science. Practical acts done well can glorify God. In this frame

of mind, the West settled into the Enlightenment.

Battle

of Rocroi, Thirty Years War

(credit:

Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, via Wikimedia Commons)

To most of the people alive at the time, it didn’t seem that the

Church’s old, traditional views were deficient, or that the views of scientists

like Galileo were better. But experiences in which people who lived by the new

ways of Science outperformed those who lived in the old way of obedience to

authority gradually won over more people in each new generation.

English

scientist/physician William Harvey

(credit: Daniel

Mytens, via Wikimedia Commons)

Some of the new belief systems were infuriating to Medieval thinkers. But

the new beliefs worked. They enabled an “enlightened” subculture within society

to navigate oceans, cure diseases, predict eclipses, boost production in

industry and agriculture, and make deadlier weapons. The new subculture was

able to increase its followers at a rate the old aristocracy and Church could

neither match nor quell, mainly because the miracles of Science can be

replicated. Science works, and you can do real-world experiments that prove it

works over and over again. These made the new model very persuasive.

Marie and Antoine Lavoisier (credit: J. L. David, via Wikipedia)

This scientific way of thinking was the way of geniuses like Newton,

Harvey, Faraday, Lavoisier, and others. They piled up successes in the hard

market of practical results. Of those who resisted the new way, some were

converted, some went down in military defeats, some worked out compromises, and

some simply got old and died, still resisting the new ways and still preaching

the old ones to smaller and smaller audiences.

By the mid-1600s, the Enlightenment, as it is now called,

had taken over.

Other societies that operated under similar world views can be found in

all eras and all nations, but we don’t need to discuss them all. The point is

that by the late nineteenth century, the memes and technologies of the

Enlightenment worldview had spread to every corner of the Earth. This view was

mainly built on the ways of thinking we call scientific. People even

came to believe that, with time and Reason, humans can solve anything; Reason

will keep producing waves of progress, and

thus, a Golden Age surely must be coming.

The one significant interruption in the spread of the Enlightenment’s

values is the period called the “Romantic Age”. The meaning of this time is

still being debated. I see it as a period of adjustment, of fine tuning a new

balance: a new social ecosystem. In the cultural evolution of our species,

values and the ways of life they enable keep society evolving into more

vigorous versions of itself all the time. The Romantic Age was a period of

finding a new balance between values that freed individuals and values that

created stability in societies. But there are a couple of especially

interesting points to note about the Romantic Age (late 1700s to the

mid-1800s).

“Wanderer Above A Sea Of Fog”

(Friedrich) (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

First, Romanticism affirmed and enhanced the value of the individual

when the Enlightenment had gone too far toward the value of duty. Too far away

from Christian values, the Enlightenment

sought to be a Greek-style of reasonable and Roman kind of practical. Some

prominent Enlightenment thinkers (especially Kant ) had made duty – to one’s family

or state – into a prime value, one that should guide all human actions.

Romanticism asserted passionately that the individual had a greater duty to his

own soul and to his own feelings: I have dreams, ideas, and feelings that are

uniquely mine, and I have a right to feel, pursue, and develop them.

Note also that, paradoxically, this individualist view can be useful for

a whole society when it is spread over millions of citizens and multiple

generations. This is because, even though most individualists create little

that is of practical use to the larger community, and some even become

criminals, a few create brilliant things that pay huge material, political, and

artistic dividends (steam engines, vaccines, universal suffrage, Impressionism,

etc.).

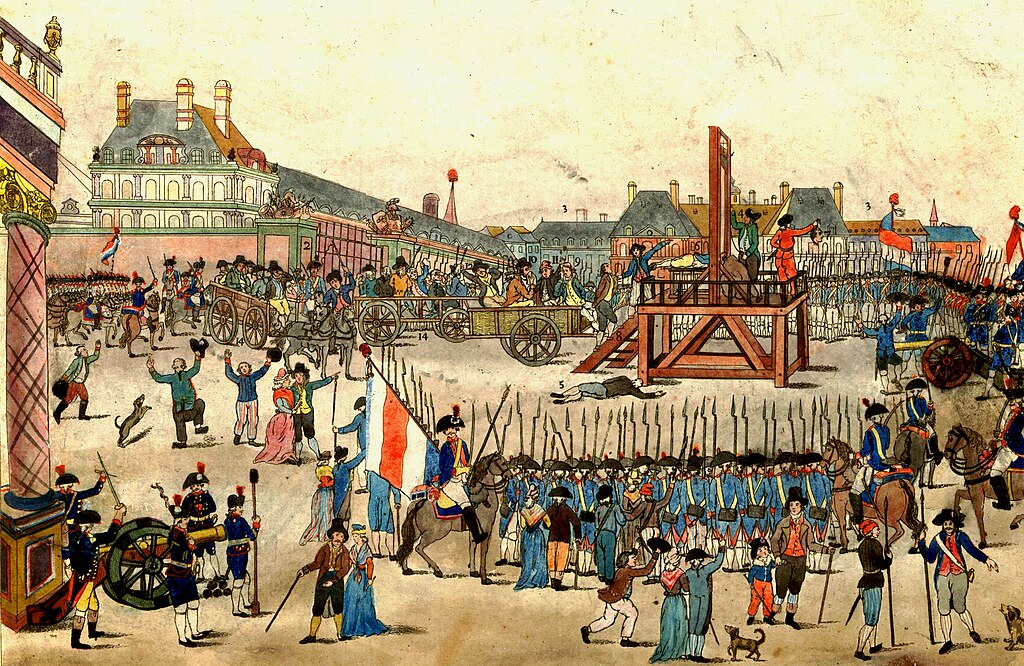

Engraving of guillotining during the French Revolution

(credit: G. H. Sieveking, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Second, however, we should note that as a political philosophy

Romanticism produced painful excesses. In France, for example, the citizens

were indeed passionate about their ideals of liberty, equality, and

brotherhood. But once they had overthrown the hereditary kings and nobles and

set up a people’s republic, they didn’t know how to administer a large,

populous state. They had many intellectual and artistic skills, but very few Roman

practical skills. In a short while, the revolution fell into increasing disorder

and internal wrangling. Then, as their state began to unravel, they simply

traded one autocrat for another, the Bourbons for Napoleon. He knew how to organize and get things done.

In the view of cultural evolution, their struggle to evolve a system of

government that could balance the most profound traits in human nature – the

yearning for freedom and the yearning for security – just took a while. Much

longer than one generation.

But the French did begin evolving resolutely toward it. After Napoleon’s

fall, a new Bourbon dynasty got control, but the powers of the monarchs were

now much more limited, and after more turmoil, the royalty idea was ousted for

good. Democracy evolved – erratically and by pain, but it did arrive and get

strong; it’s still evolving in France, as is the case in all democratic states.

Aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, 1863

(credit: Timothy H. O'Sullivan, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the United States, Romanticism attempted to integrate the

Enlightenment ideals of reason and order with Romantic ideals that asserted the

value of every human individual. The struggle produced excesses in America as

well: the genocide of the native people, enslavement of millions of Africans,

and one of History’s worst horrors, the US Civil War.

The example of the indigenous peoples of the New World and how they were viewed by Europeans is instructive. Even Enlightenment thinkers assumed Europeans had built superior societies. They were “bringing civilization” to the other "races” of the world. It was obvious to Reason. Therefore, short-term excesses by European traders, priests, or armies could be overlooked. The long-term effect would be for the "primitive” tribes’ benefit. That made colonialism acceptable in the “Enlightened” view.

Stu-mick-o-sucks,

Blood tribe chief

(credit: George

Catlin, via Wikimedia Commons)

But for Romantic thinkers (Rousseau), the native people of the "New

World" were "noble savages", morally superior to the Europeans

who were exploiting them. Rousseau argued that Europeans should be seeking to

live more like them, close to nature, not trying to make them like Europeans.

Both views were extremes that lacked nuance and/or commitment to looking at

evidence in the real world. Neither offered many ideas that eased the actual

interfacing of native and European cultures, and the subsequent suffering of

the natives.

For example, North American native peoples needed vaccines long before

they began to get them. European diseases were ravaging their tribes, killing

as much as 90% in one generation. Smallpox especially was preventable from 1796

on, but among native peoples epidemics continued to occur long after the

vaccine had been found. Neither Romantic values nor Enlightenment ones

moved white leaders toward vaccination of native people until generations after

when it first could have been done. Enlightenment gurus believed the natives

must first come into the white people’s towns and accept the enlightened way of

life – farming, trades, etc. Romantics wanted to leave them as they were on their

own lands which whites didn’t violate. In practice, neither view helped real

people much. Native people didn’t want to adopt the white people’s ways, yet

they kept coming into contact with them, sometimes due to whites’ movements, sometimes

their own. The results were neither Enlightened nor Romantic, i.e. neither

reasonable nor compassionate.

On the other hand, as we are finding out now, the indigenous people really were superior to whites in some ways. For example, the Innu in Alaska knew that when beaver get too plentiful, their dams block salmon from spawning, and then beluga whales that feed on the salmon drop in numbers. In other words, ecological concepts were known to indigenous people long before Euro-based people began to grasp them. It was an area in which the indigenous people's wisdom might have helped European fishers, farmers (who should not shoot owls, for example), and ranchers - if they’d been willing to listen.1

The sensible view would have told us that each society had things to

learn from the other. That would be the moral realist view. If it is any

consolation, we are beginning to see now that every society that has made it

this far in human history has valuable parts in its cultural code, parts that

other societies can learn from and profit by.

America had to undergo some difficult adjustments before it began to

integrate the Christian belief in the worth of every individual with the

respect for the law that enables individuals to live together in peace. But the

slaves were freed, and the government began to compensate the native tribes and

take them into the American mainstream. Or rather, to be accurate, America

began moving toward these more balanced ideals with more determination and

continues to do so into this era, as do all modern democracies.

Thus, in the larger picture of all these events, the Romantic Age

imprinted into the Western value system a deeper respect for the ways of

compromise: the “better angels of our natures” that Lincoln spoke of. The

result was modern representative democracy. Its values guide people toward

balancing progress with order. They keep democratic countries from devolving

into chaos. Our best hope for creating institutions by which people use reason

and debate instead of war to find balance in each generation – balance between

security-seeking conservatism and the reformers’ passions – is democracy.

Lesser sideshows in the swirls of human history happen. These are

analogous to similar sideshows that have happened in the biological history of

this planet. Species and subspecies of animals and plants meet, compete,

mingle, and then thrive or die off. So do species of societies. But the largest

trends are still clearly discernible. The dinosaurs are long gone, and so are

many obsolete societies. New species of societies keep emerging. It is also

worth noting that events of this age prove that war is not the only path by

which this process can work. During this era, Britain ended slavery in her

Empire – without a war.

In a compromise, two opposing parties each give up a bit of what they

want in order to get a bit more of what they need. But what happened during the

Romantic Age was a melding of two very different ways of life. As conditions

changed and old cultural ways became obsolete, a new species of society arose:

representative democracy with universal suffrage. And it proved vigorous.

The idea of democracy evolved until real democratic states formed, ones

that were built around constitutions and universal suffrage, not titles or

traditions. The constitutions stated explicitly that protecting the rights of

every citizen is the most important reason for democracy’s existence. This

change came about by the hybridization of Christian respect for the value of

every human being, Roman respect for order and discipline, and Greek love of

abstract thinking: thinking that questions all the forces that be, even those

in the physical world.

Representative democracy based on universal suffrage became the goal of

the Renaissance and Enlightenment world views when they were applied by human

societies to themselves. The Romantic Age showed that the adjusting and

fine-tuning takes time, and sometimes also pain. A state that says it values

human rights must deliver them or else dissolve in chaos.

In the meantime, as Romanticism raged on, what of the Enlightenment

world view? Inside the realms of Science and Industry, the Enlightenment was

still in place and actually getting stronger. The Romantic revolt left it

changed, but invigorated. Science came to be envisioned by scientists as the

best way to fix society’s flaws. Industry could be managed, by Science, so that

it made plentiful goods of high quality, produced in humane ways, affordable

for all.

Under the Enlightenment world view, the one of Newton and Laplace,

events were seen as results of previous events that had been their causes.

Every single event became, in an inescapable way, like a link in a chain that

went back to the start of the universe. The universe was ticking down in a

mechanical, irrevocable way, like a clock. (This view is called determinism

in Philosophy.)

While the Romantic revolt ran its radical course, governments,

businesses, industries, armies, schools, and nearly all society’s other

institutions were still quietly being organized in ways suggested by the

Enlightenment worldview. The more workable of the Romantic ideals (e.g. relief

for the poor, protection of children) were absorbed into a new worldview that

kept spreading till it reigned, first in the West, then gradually in the world.

Crewe locomotive works, England, c. 1890

(credit: Wikimedia Commons)

At this point, it is important to stress that whether or not political

correctness approves of the conclusion we are heading toward, it is there to be

drawn and therefore should be stated explicitly. The Enlightenment worldview

and the social system it spawned got results like no other ever had. European

societies that operated under it kept increasing their populations, their

economic outputs, and their control of the physical resources of the Earth. A

steam shovel could outwork a thousand human shovelers. Western Science produced

weapons that rolled over all the non-Western ones that opposed them.

But it is also important to stress that the Westernizing process was

often unjust. Western domination of this planet did happen, but in the

twenty-first century, most of us will admit that while it has had good

consequences, it has had many evil ones as well.

Naval

gun being installed, New York Navy Yard, 1906

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

The conclusion to be drawn from all this is that the Enlightenment

worldview, with the moral code that attends it, is no longer an adequate code

for us to live by. It is ready for an update. In the midst of its successes, it

has also produced huge problems like the oppression of women and minorities,

class inequities, wars, colonialism, the proliferation of nuclear arms, and

pollution levels that will destroy the Earth’s ecosystems if they’re allowed to

continue unchecked. Some problems are out of control. Even more frightening,

the Enlightenment worldview appears to have run out of ideas for how to solve

them.

But the larger point of this long discussion of the rise of the West is to

see that worldviews give rise to value systems and value systems give rise to

morés. The morés then cluster to form a way of life that has a survival index

in the real world. Furthermore, some morés and habits of living, when they come

to be believed and practiced by the majority of a society’s citizens, increase

that society’s survival odds more than others do. By our morés, and the

patterns of behavior they foster, we interface with reality. Then, if our

values and morés are well tuned to reality as it exists in our time, we thrive.

But I stress again that the worldviews, values, morés, and behavior

patterns that we humans live by do not, as cultural relativism claims, all have

equal survival indexes. They also are not part of our way of life because of

random events in the world or impulses in us. In the moral realist view, human

values are not shaped by forces humans can’t influence. Instead, we can shape

our own values and way of life. In the past, we have not done so very well. But

we could learn to do better, and so, to re-write the code that drives us.

The point of my last two chapters has not been to show

that the ways of the West are always the best. What my last two chapters

have shown is that, first, beliefs have consequences in the physical world for

the folk who live by those beliefs; and, second, that some belief systems get

better results than others.

We needed to grasp the mechanism of human cultural evolution in order to

move on with our project. We’ve now done that. We’ve shown that human history

does have a system to it; and, second, that we can intervene in that system and

maybe, if we act with a coherent vision – that of Modern Science – we can learn

to direct that system toward maximum health for us all.

The new worldview Science is offering, and the values and morés it

fosters, are so different from the one out of which the success of the West

grew that the cultures of the West seem to be verging on self-destruction as

they try to adjust. The obsolete parts of the Western worldview will be

replaced. All worldviews, morés, and cultures get updated eventually. The

difference in our era is that, if we work hard to ensure that they are not

replaced by others that lead to new forms of injustice, we may move on without

causing another Dark Age or worse: our own extinction.

With the problems and hazards that we have before us now, there is

little hope for our species if we don’t learn to manage ourselves.

Discussion of the moral implications of the worldview of Science will be

the business of my next two chapters. The cultural evolution theory presented

in this book offers guidelines by which we can design a new society. This

theory is a corollary of the Theory of Evolution. It can describe for us

generally how we should proceed if we wish to maximize our odds of surviving. It

cannot tell us exactly where we will be in a hundred years. We will have to

adjust our path into the future as the challenges arise. Humans have always

done so.

The general, energetic forward push of life is a given for all life

forms. Living things push out into the space about them, adapt, and flourish or

else die out. We humans, with our culture-driven way of evolving, could be

destined for space travel and colonizing new planets. It's what we're

programmed for, and there is no compelling reason why we can’t do it if we come

together.

Now let's return to our main project.

I will combine the insights of three fields of study to build a new code

of right and wrong: the physical sciences, the life sciences, and this new

model of cultural evolution.

My goal is to provide an outline of a

new moral code that all reasonable people can commit to simply because they can

see that it is consistent with all we currently know of our universe and our

life in it: a universal moral code that is clearly consistent with physical

reality.

If we are to persuade humanity to move past war, first, we must make

sense.

Notes

1. Huntington, Henry,“Traditional Ecological Knowledge And Beluga

Whales”; Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine, September, 1998.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.