Chapter 17

The Morally Crucial Features Of Modern Physics

We’re now ready to tackle the moral challenge, to derive ought

from is. The question now is: How would a moral code based on the most

general principles of empirical reality work?

Note again that it’s the big constants of the universe that we want to

resonate with. Our moral code, if it is well-designed, should match our best

worldview: Science. Even when we know what the constants are, we will still

have many ways in which to design a society with strong survival odds. This point

about there being many possible cultures that could live in any given

environment is what relativists keep telling us. But the larger point is that,

whatever design we choose, we will have to accommodate the principles of

Physics. Moral relativism offers no guidelines at all for us to follow as we

design a new moral code for society. Moral realism tells us to look at the

basic forces that are in every environment and begin to build our moral code

there. This is the crucial difference between the two.

Note also that the room for huge variety in culture designs for many

different actual societies is really only an indicator of just how free

reasoning beings are in this universe. We are free to such a grand degree that,

as the Existentialists say, it scares many. But it is exhilarating to others.

Imagine. Go for it. Live creatively. These are the maxims for real humans in

this universe.

An analogy with the biological world fits well here. Life forms are so

varied that a biologist can get absorbed in studying any one of millions of

species for the rest of his life. But there are giant constants that are

essential for all living things: for example, respiration, by which all living

things get energy. Or pH. Or temperature. To understand life, we first seek the

big constants, the ones that govern life for paramecia, parrots, people, and

piranhas. Similarly, to understand cultural evolution, we must grasp how the

largest principles of reality inform, or at least should inform, our moral values.

For our moral code, the two most

important features of the worldview of modern Science are entropy and

uncertainty. Thermodynamics

teaches us about entropy, Quantum Theory about uncertainty.

Understanding entropy means we must accept that the universe is heading

toward a final state in which all the universe’s most basic particles will be

spread evenly across it at a temperature of 0 degrees K.. We don’t understand numbers

that big, but that doesn’t matter. Physics tells us that the heat death of the

universe is inevitable. (In about 5 billion years.) On an hourly, human scale, entropy simply means that all things constantly tend to fall apart and burn out.

To humans, who are energy-concentrated living things, this means we

exist against the natural flow of the physical universe. The level of

disorganization, entropy (“burnt-outness”) of the universe is always

increasing. This is the first major thing that Physics has to say to Moral

Philosophy: life is always hard.

(credit: Profberger,

via Wikimedia Commons)

The second feature of reality that matters to our moral code is

uncertainty. In order to adapt to uncertainty, obviously, humans must strive to

learn to make provision for all the possible future events that we can.

Probabilities of future events range from the likelihood that it will

rain today, to the likelihood that there's a leopard nearby, to the likelihood

that Germany will attack Russia, given what Hitler said in Mein Kampf

about Germany’s need for living space. We live by odds-making. Life is hard and

also scary.

Our belief that life is full of toil is our way of understanding

entropy. Our belief that life also contains constant hazards, in addition

to the constant toil, is our way of understanding uncertainty. For individuals,

families, tribes, and nations, adversity and uncertainty characterize life all

over all of the time.

Over thousands of years and billions of people, values enable the

survival of a society only if those values reflect the forces underlying

physical reality; or, to be more precise, successful values must cause humans

to behave in ways that accommodate adversity and uncertainty, especially for

whole societies over the long term. Successful values, riding in their human

carriers, thus endure.

Our values in modern democracies have been fairly effective at guiding

us to survive and spread, though not always in humane ways. Over millennia, the

demands of survival in a hazardous reality have caused us to work out a set of

values, morés, and behaviors that (mostly) guide us to handle both adversity

and uncertainty. If we and our forebears had not learned and implemented these

basic value lessons at least moderately well, we wouldn’t be here. Having

children is hereditary: if your parents didn’t have any, you won’t have any.

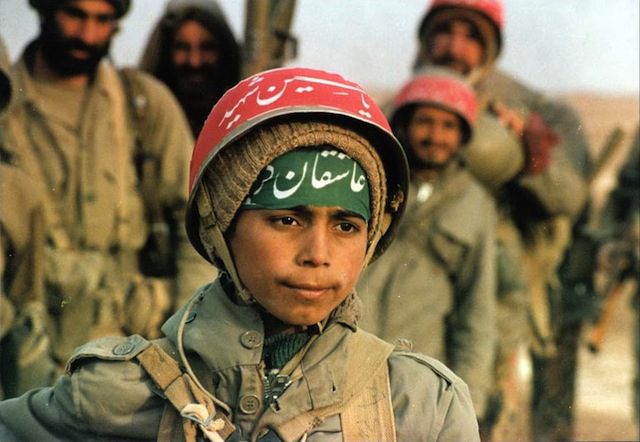

Below are pics of children being programmed into

the values of their cultures.

Young patriot (credit: US Army, via Wikimedia Commons)

Chinese

children (PRC) in Young Pioneers (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Russian children in

Vladimir Lenin Pioneers (1983)

(credit: Yuryi Abramochkin, via

Wikimedia Commons)

Iranian

boy soldier during Iran-Iraq War (1980 – 88)

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

But we don’t yet comprehend these big truths of reality in a conscious

way.

Most people of every nationality still see their values as being exempt

from analysis because they get programmed as children to be deeply,

unswervingly loyal to their tribe’s ways. This kind of programming has made the

majority of people in most societies, both historical and modern, into

unthinking pawns of their tribe’s culture. A major purpose of this book is to

help thoughtful readers become aware of values and draw them into consciousness

as concepts that they can analyze and discuss rationally.

Thus, we are now ready to ask: What are the values that enable humans to

respond to entropy, the uphill struggle of life, the adversity that is a

given for all things that live.

A whole array of values should be taught to young people to enable them

and their culture to deal with adversity over generations and centuries. In

order to deal well with adversity, a society needs large numbers of people

willing to face exertion, exhaustion, struggle, and pain. In fact, a society

proves most effective if its citizens take up the offensive against the

relentless decay of the universe.

Children taught to seek challenge become

adults who bring new territories (one day, planets) under their tribe’s

control, devise new ways of growing food and making shelters, devise technology

to do more work with less exertion, and generally perform the tasks of survival

more efficiently.

When we generalize about what these entropy-driven behavior clusters have

in common, we derive two large, generic values that are found in all cultures: courage and wisdom.

In different cultures all over the world, courage is instilled in the

young, which is what we’d expect if it works. Bergson spoke of élan,

Nietzsche, will.1 Honor and discipline are also

terms that serve well in most contexts for this same cluster of values. Face

adversity, kids. In fact, go at life. Tackle it head on.

Japanese samurai lived by bushido, their code. European

nations by chivalry, right into modern times. Beyond the difficulties of

translation from culture to culture, we see in all these varied values a common

motif: they all direct disciples to persevere through, even seek, challenge. In

ancient Greek myth, Achilles chose a brief, hard life of honor over a longer,

easier one of obscurity. For centuries, the ancient Greeks considered him to be

a model of a man, as do some people to this day in nations that admire the

values of ancient Greek culture. Many non-Western cultures have similar heroes.

The Triumph of Achilles (credit:

Franz Matsch, via Wikimedia Commons)

Photo believed to be of Apache leader Crazy Horse, c.

1877

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

Statue

of Zulu leader, Shaka

(credit: Jacob Truedson Demitz, via Wikimedia Commons)

Martial arts

master and Chinese hero, Huo Yuanjia

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

Confucius said the superior man thinks always of virtue, while the

inferior man thinks always of comfort. Nineteenth-century English writer K.H.

Digby said: “Chivalry is only a name for that general spirit or state of mind

which disposes men to heroic actions and keeps them conversant with all that is

beautiful and sublime in the intellectual and moral world”.2

The exhortation to seek adversity, and reject easy lifestyles, echoes

through all societies. Young people everywhere are encouraged to tackle hardships,

especially for the defense and promotion of their nations. We can sum up the

gist of all of these values by saying that they are built around the principle

that in English is called courage.

It is familiar and cliché to push young people to aspire to courage. But

clichés get to be clichés because they express something true. In the hard

background of the physical universe, life seeks to create pockets of order. In

the case of humans, it does so by programming into young people an entire

constellation of values around the prime value called “courage”. Behaviors that

meet and overcome adversity enable those who practice them to move forward. Societies

that value courage survive and spread better because of that value.

And now we come to a subtler insight. The value society instills into

its young to make them seek out and conquer adversity must be balanced with a

second value that will cause the energy put into facing challenges to be

focused so the individual will deal with challenges efficiently. Nothing is to

be gained by teaching young people blind aggression; it will only run amok in

its own society. Eager-but-directionless young people end up hurting themselves

in car crashes, daredevil stunts, and street fights, while accomplishing little

or nothing in useful, material terms for their nations.

The courage-tempering value is usually called wisdom, but knowledge

and judgement are also terms in English related to this same value.

Wisdom has the effect of focusing human actions to achieve objectives by

behavior patterns that use energy efficiently. It is seen in the medieval knight’s

code of chivalry and the samurai warriors’ code of bushido,

both of which contain instruction on how a man may be both brave and smart.

Warrior and poet.

Note that the idea of balance is implied all through my model.

Societies, like living species, become extremely complex, internally and in

their dealings with each other. An individual has to hold his internal traits

and forces in balance in order to function. But balance is an ideal in all

cultures.

Aristotle told his followers to seek moderation. For example, in his

view, balance between foolhardiness and cowardice is what makes courage. And

stinginess must be balanced against extravagancy if we are to reach a prudent

way of handling money; and so on for a whole list of virtues.

The religions of the East, like Taoism and Buddhism, go so far as to say

that even the whole picture our minds have of all reality as being made of opposite traits is illusory. Buddha

and Lao Tse saw reality as an unbroken, seamless whole.

Our minds think they see separate entities like animal and plant,

garbage and food, rich and poor, life and death, past and future, but in

reality, there are no such things. The words only name illusions. We get free

of our suffering, they say, when we let all our categories go and become one with everything. Then,

with awareness of the true nature of reality, even the most tedious forms of

work can be done with mindfulness and dignity. Scrubbing a pot, weeding a

garden, or digging a ditch can all be dignified if they are done

mindfully.

A fascinating insight into how cultures teach this balancing of courage

and wisdom lies embedded in myths. Myths were the life-guides for early tribes.

The Greek mythic heroes Achilles, Jason, Perseus, Theseus, and Aeneas all

needed Chiron, the wise teacher: courage plus wisdom. In myths of the early Britons,

Arthur needed Merlin. In modern myths, Luke Skywalker needs Yoda; Dorothy,

Glinda; Katniss, Haymitch. Courage tempered by wisdom.

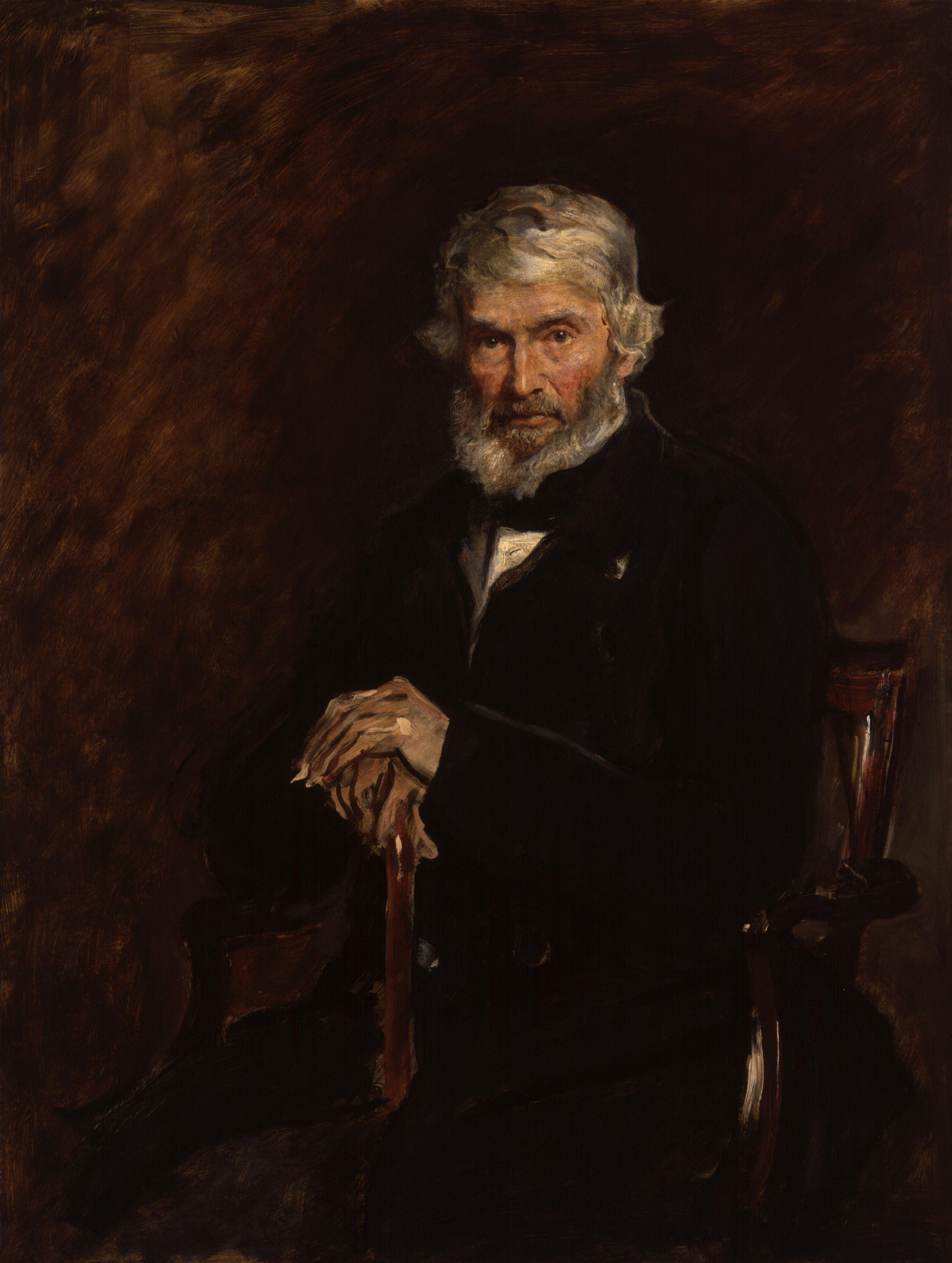

Thomas

Carlyle (artist, J.E. Millais)

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

The most familiar value that is a hybrid of courage and wisdom is what

we call work. Diligence and conscientiousness are

two of its other names, as most of us are wearily aware. But the tedious,

clichéd feel of this values cluster should not discourage us. Clichés, as I’ve

said, like this about the nobleness of work, become clichés because they

express something that is universally true.

“I'm a greater

believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it.” (Thomas

Jefferson)

“Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.” (Edison)

Courage is good. Wisdom is good. We learn as children that if we want to

achieve great things, we must learn both courage and wisdom. Be brave, but also

smart. In practice, the combination of the two always means hard

work.

Thomas Carlyle distilled the idea well:

“For there is a perennial nobleness, and even sacredness, in Work. Were

he never so benighted, forgetful of his high calling, there is always hope in a

man that actually and earnestly works: in Idleness alone is there perpetual

despair. Work, never so Mammonish, mean, is in communication with Nature; the

real desire to get Work done will itself lead one more and more to truth, to

Nature’s appointments and regulations, which are truth.” 3

Democratic

pluralism: the first cabinet of Barack Obama

(credit:

Chuck Kennedy, via Wikimedia Commons)

This is the moral realist view of how the fact of entropy informs the

values and behaviors of human societies. A lot of varied societies can emerge

in real life, but all that last must teach hard work as a prime value. The

giant picture we’re drawing here leaves plenty of room for variety in human

cultures, but they are not chaotic and random, as moral relativism would have

us believe.

But what about the second big trait of reality, namely quantum

uncertainty?

As with courage and wisdom, a balanced pair of values shapes the

behavior of citizens as societies strive to deal with uncertainty. To maximize

its chances of handling the uncertainty of existence – the unexpected events

that keep coming at us – a society must contain as wide a variety of responses

to the challenges of the physical world as the people in the society can learn

to master. In a scary world, if you’re smart, you try to learn skills that will

make you resourceful and versatile so that you can be ready for almost

anything.

Encouraging individuals to be versatile (the Renaissance man

concept) helps, but the really important value a wise society instills into all

its members is a love of freedom: a desire in every child to develop his

talents. And it works best if it partners with a generous spirit that

encourages others to do the same.

To be equipped to meet the widest range of futures possible, a society

must contain the widest range of humans possible, with skills and talents of

every sort imaginable. If an unforeseeable crisis threatens a freedom-loving

society, that society has a higher likelihood of containing a small group of

people, or even just one individual, who will be able to react effectively to

the situation than a more homogenous society ever can. Then the effective ones

can teach the rest how to survive the current crisis. The free society is tough

because it has many kinds of folks to draw its resources from.

In addition, in more ordinary times, when a society is maintaining a

steady state, the people in a diverse society pursue a wide range of

activities, research a wide range of topics, and develop a wide range of

services and products. Any of these may yield benefits for the whole society.

Against the uncertainty of the universe, societies that are free and

courageous even become proactive.

Which activities will turn out to be more than just hobbies in a decade

or two can’t be known in an uncertain universe. Some of these hobby activities

will fit into the society’s social ecosystem and, in a decade or so, become

simply parts of the division of labor. Others will prove to be silly wastes of

time. Still others will lead to innovations that will make that society leap

forward.

Therefore, a wise society cultivates diversity and also cultivates its

dreamers. Occasionally, an eccentric invents something that is amazingly useful

to all. The presence of eccentrics in a society is proof that freedom is

part of that society’s moral code. In any society, in the long run, the more

uniform its people are, the lower its odds of survival are. On the other hand,

pluralistic societies adapt better to challenges, and thus, over generations,

they survive.

To balance this value called freedom in the way wisdom

balances courage, society must teach love. Left unbalanced, freedom

leads to fissioning. Factions form, and gradually become mutually suspicious

and hostile. To balance the hazards of freedom, we teach love, brotherhood. As

courage plus wisdom yields work, so freedom plus love yields democracy. Love

makes us strong.

A society with a wide range of behaviors and lifestyles practiced among

its citizens must also teach these citizens to respect one another’s rights. If

it does not, that society will be constantly torn by violence between its varied

factions. No matter which wins, some of that society’s versatility will be

lost, a net loss for all. Thus, in all long-enduring

societies, some form of love for one’s fellow citizens has always been

taught to each new generation.

New technology:

cannon ca. 1430

(Jan Rehschuh, Wikimedia Commons)

The most basic form that this love takes is mutual respect, and it is

realized in the rule of law. In a democracy, laws are drawn up by

representatives of the people. In an autocracy, the laws are whatever the

autocrat says they are, but since he is just one person, the laws tend to be

inconsistent and inadequate. (This is why most autocracies end up using

repression to keep people in line.)

Thus, in a democracy, the citizens must cooperate to build and maintain

a legal system that will enable them to work, do business, raise families,

settle disputes, and through all these activities, live in communities and get

along.

But laws can only work if the people living under them respect not just

the exact wording of their laws, but the spirit or intent behind them. When

large numbers of citizens begin to see their laws as unjust, they start to

circumvent those laws. The justice system becomes less and less effective. Then

too many offenses go unpunished, a bad sign for any society. Anarchy is about

to ensue.

In our work as students of cultural evolution, one thing to note is that,

in History, causes and their effects can take generations to connect. A

decadent society, whose citizens no longer live by their values, deteriorates

gradually into corruption, rebellions, and anarchy. For students of History,

mounds of irrelevant trivia can obscure their view and keep them from seeing

how decay in a society’s belief system produces effects in the daily lives of

its people. Why did they win this war or lose that one? Did they fall because

of this famine or this plague? The wars, famines, and plagues are usually not

the prime causes of any civilization’s fall. The cause of a civilization’s fall

is moral decay. When most of a nation’s people are living by their values, it

handles challenge. When its people’s values decline below a critical threshold,

that society will fall to the next hard challenge it

encounters.

But we should not be surprised at the gradualness of the processes of

History. In truth, they only seem gradual in the limited view of the

individual. A thousand years is fifty human generations. In terms of biological

evolution, fifty generations is trivial. In genetic evolution, hundreds of

generations often have to pass before a new anatomical or physiological feature

in a species can prove its usefulness.

On the other hand, the evidence of History indicates that a new belief,

with its morés attached, even though it looks slow-acting in our eyes, often can

prove itself much more rapidly than a new anatomical or physiological trait

can. We can see the workings of human cultural evolution in action if we know

what to look for. For example, Renaissance Science – with its curious spirit,

its freeing of minds from the superstitions of the Middle Ages, its belief in

the physically-caused nature underlying events, and its rigorous method of

theory-forming and testing – created better and better guns. For people in

those times, guns changed everything. In one generation, knights were out, musketeers

were in.

Note also that even when sometimes it moves more slowly, cultural

evolution is much more efficient than genetic evolution: cultural evolution

responds to changes in the environment more quickly and effectively than does

genetic evolution. Since Enlightenment times, in fact, humans have been getting

better at altering Nature herself. We don't wait for Nature to hit us with a challenge

anymore; we go over to the offense and dominate Nature faster than we once did.

A drug may cure a disease, but a vaccine may prevent that disease.

In any case, the cause-effect connection between a human society’s

ideals and customs and its success in the material world is always there for us

to see if we look hard enough. We just have to study a lot of societies and a

lot of belief systems; then, we begin to see the balances among, and

connections between, courage, wisdom, freedom, and love and their consequences

in plentiful goods, control of disease, military success, etc..

Plagues, famines, wars, etc. are readily dealt with by a society that

has the values of courage, wisdom, freedom, and love in place. Natural

disasters are just the uncertainty of the universe taking physical form. These

too are dealt with by democratic societies. To meet universal uncertainty at

its inception – whatever form disaster is about to take – successful societies teach

and practice courage, wisdom, freedom and love. Then, material achievements –

greater technical advances, harvests, birthrates, territory, etc. – arrive.

It is also worth pointing out here that some societies in the past even

worked out sets of beliefs and customs that enabled them to live and multiply

so well that for generations, their elites came to believe they had found the

answers to life. These citizens created niches that were insulated from contact

with the adversity and uncertainty of the material world. Then, their belief in

their values deteriorated till they came to regard the values that had first

enabled their society’s success, as obsolete, old-fashioned notions.

In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. In reality, we must

deal with reality. It keeps being adverse and unpredictable, demanding courage,

wisdom, freedom, and love of all citizens if their society is going to stay

strong. What can confuse an analysis of History is that when citizens do begin

to get lazy about living their values, the crash of their society may take a while

to arrive, and its cause may be hidden by a lot of trivia, but the crash will come.

It is also worth noting again that the numbers of cultures possible that

would qualify as brave, smart, free, and kind is near infinite. If we brought

together all the records from all the cultures that have ever existed, this

would still give us only a tiny fraction of the number of cultures possible.

We’ll never observe in History every way for us to respond to adversity and

uncertainty.

Therefore, we must search through the records of all human societies for

the larger principles and try to accumulate what knowledge we can about them if

we are to steer our species as it moves forward through time. Wisdom, the knowledge that really works, has been long,

hard, and slow in coming.

But however hard all that reading, thinking, debating, and writing has

been, as much in our own times as in any past era, it has to be continued. From

those mounds of historical data, our minds must extract the principles that we

need to save ourselves from ourselves. The alternative is to resign to

disaster.

University

of Virginia: Modern scholars

(credit:

Mmw3v, via Wikimedia Commons)

Some people in every era don’t want to study the past. Such studies

might lead to change. They resist change as automatically as they breathe. They

want to stay with what they were raised to because it feels secure. But if we

don’t learn from the past, if we don’t constantly strive to get wiser and adapt

more rationally to the changes in reality, then reality comes for us. We can’t

hide from change. The one alternative strategy is to go at life hard.

Freedom, as a value programmed into children, is vital to society. It

drives us to develop our talents and live motivated lives. It pushes us to

handle change. But, if it weren’t complemented with love, freedom would beget

cliques, gangs, and factions, then prejudice, hostility, violence, and anarchy.

Brotherly love, as a widely held value, solves this dilemma. In Roman

times, for example, love seemed so crucial to Jesus that he told his disciples

to place love above all other virtues. He said that it was the one thing he’d

taught them that they must not forget. Implicitly, he was saying all other

values – even courage and wisdom and their benefits – arise from love.

“A new commandment I give unto you, that ye love one another as I have

loved you. By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have

love one to another.” (John 13: 34-35)

Thus, humans sustain and spread their societies by practicing lifestyles

that seem paradoxical to any who look for all phenomena to be reduced to simple

parts. Freedom must be balanced with love. In balancing these values in our

daily lives, we mirror the balance principle of the ecosystems of the earth.

Competition and cooperation are always in balance in every creature’s life,

even for a shark. She can’t reproduce by eating everything she encounters.

This is basic systems theory. We couldn’t survive in this uncertain

reality, as individuals or societies, if our lives were otherwise. And balances

are tricky to find and maintain. But who really expects life to be easy?

Freedom is a precious, beautiful thing. If the price of it is maintaining a

loving attitude and standard of respectful conduct as we deal with our

neighbors, there is a deep sense of symmetry to that picture. A decent way of

life for an individual or a society requires constant adjusting and is hard to

sustain. But not impossible.

Therefore, we need internal tensions in our communities. Pluralism is a

sign of a vigorous society. Monolithic, homogeneous societies lack

resourcefulness. A democracy may seem to its critics to be enervated by the

energy its people waste in endless arguing. But over time, in a universe in

which we can’t know what hazards may be coming in the next day or century,

diversity and debate make us strong. Wishing to escape uncertainty and anxiety

leads us away from love for our neighbors, away from pluralism and freedom. And

love is not just “nice”: it’s crucial. It has carried us this far; it is all

that may save us.

A basic Buddhist truth is that life is hard. Another is that only love

can drive out hate. Jesus’s prime command to us all: love one another as I have

loved you. These codes have not survived because a bunch of old men said they

should; they have survived because they enable their carriers to survive. In

short, our oldest, most general values have survived in us because they work.

The

Debate of Socrates and Aspasia

(by Monsiau) (credit: Wikimedia

Commons)

Now let us sum up this chapter. Courage is the cultural response to

entropy. Wisdom balances courage. Freedom is the cultural response to

uncertainty. Love balances freedom. Diligence, humility, and many other values

are hybrids of the four prime ones. They are not easy to see in action; they only

show their usefulness on

a huge scale as the daily actions of millions of people over thousands of years

keep evolving and keep getting, for the followers of the best tuned value

codes, better and better results.

But values are not, as some postmodernist moral relativists wish us to

believe, trivial or arbitrary preferences like preferences for certain flavors

of ice cream or brands of perfume. Values are cultural responses to what is

real.

In the next chapter, we shall strengthen the case for belief in the

empirical realness of moral values by showing some ways in which the cultural

model of evolution closely parallels the biological model of evolution, the one

by which we understand life on this planet and how it grows and changes. At

that point, the case for moral realism will be proven. Perfectly? No. In

quantum reality, we don’t get perfect proof. But more than adequately, by

Bayesian standards.

And for theistic readers, I will also say that theism is coming. Hang in

there.

Notes

1. Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book

for All and None, Part XXXIV, “Self-Surpassing” (1883; Project Gutenberg).

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm#link2H_4_0004.

2. Kenelm Henry Digby, The Broad Stone of Honour; or, The True

Sense and Practice of Chivalry, Vol. 2 (London: B. Quaritch, 1976).

3. Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present, Chapter 11 (1843; The

Literature Network).

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.