Chapter

18 The Genetic Evolution – Cultural

Evolution Analogy

Earth seen from space (Wikimedia

Commons)

What

makes Earth’s biosphere – its living ecosystem – so different from any other

entity we have found in the universe (so far) is the way it tends, overall, to

keep becoming more – more in its mass, in the space it occupies, and in its

complexity – as it moves forward in time. All other entities known to us shred

apart across the time axis. But life on this planet has formed complex entities

that keep weaving in more matter and energy. Living things take bits of dead

matter, plus already existing living fabric, then, using directions coded into their

own parts, they weave these into more of themselves. Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, and

Nitrogen woven on sunlight-powered looms, following directions coded into DNA,

ultimately form one giant garment. Earth’s biosphere.

This

weaving metaphor is an inadequate one, but then so are physicists’ models of

matter. All models used in Science prove limited. Electrons are not tiny balls,

even though that’s how they’re portrayed in high school Science texts.

All the

metaphor is meant to help make clear is that as this entity expands, there are

patterns visible in that expanding. Those patterns can be seen repeating and

also subtly evolving, ceaselessly. It is just logical for us to assume that they

must be guided by some programming embedded somewhere in the fabric.

We have shown

in the life sciences that most of the species in the system get the programming

they use to regulate how each species member maintains its body, how it reproduces,

and how the species as a whole adapts to changes in its surroundings, from

microscopic bits of matter woven into each species member. That is, all that

information is coded into these bits of matter we call “genes”.

Only one

social species, the human, gets even more of the programming it uses for

maintenance, reproduction, and adaptation from memes programmed – via language

– by older members of the species into the brains of the young.

Living

by their cultural codes, i.e. by learned behaviors rather than genetically

coded ones, humans outmanoeuvre all other species on this planet. But we must bear

in mind always that, in the end, societies have to survive in the same universe

run by the same laws as all living things do. Cultural programs must guide us

to deal with gravity, light, entropy, uncertainty, pH ranges, moisture levels, and

so on, just as genetic programs do. Culture enhances genetic codes. It does not

replace genetic codes. And both aim at the same end: survival.

Thus, it

is logical for us to digress on the analogy that can be drawn between the

genetic mode of evolution and the cultural one. This analogy will help to deepen

our understanding of cultural codes, and so of moral realism.

Parallels

between biological evolution and cultural evolution have been noted before, by

the Social Darwinists in particular. But most people today consider the Social

Darwinists’ conclusions disgusting. And rightly so. To put it bluntly, Social

Darwinists argue that rich people are rich because they deserve to be; they are

superior. They deserve to be rich because they know how to run society. They

have both the intelligence and the discipline to keep society stable and to get

things done. In contrast, these rich people claim the workers, who in many

places in the world are still indigent and living in squalor, deserve to live

in misery because they don’t have the intelligence or discipline to run

anything.

"The

storming of the Bastille"

(credit: Jean-Pierre

Houël, via Wikimedia Commons

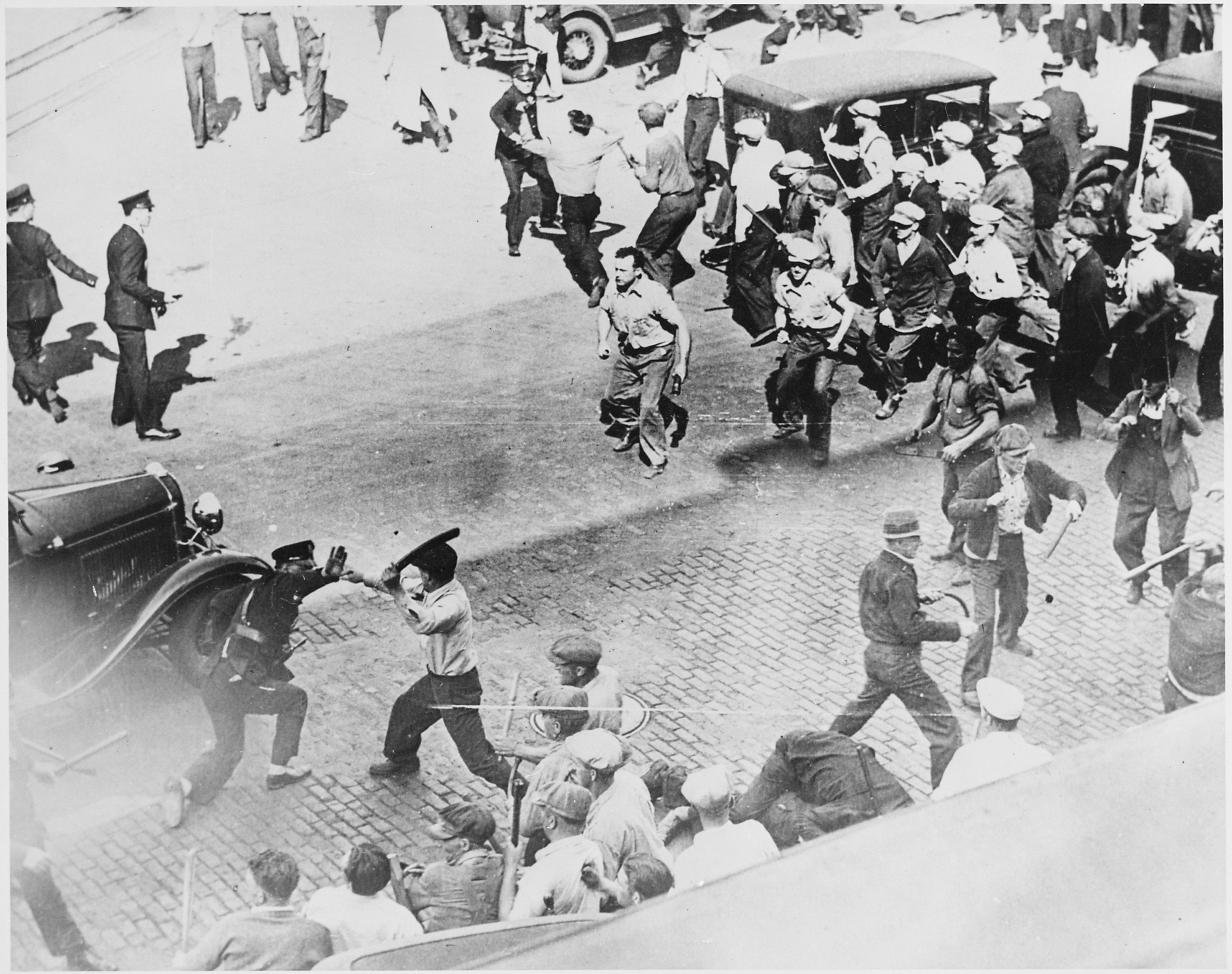

A few generations ago, some rich Frenchmen lived by this code and found to their sorrow that it contained the seeds of its own destruction. To persuade any who still want to live by that oligarchic code, I offer the harsher lessons of the Russian Revolution. Then come the ones in China, Cuba, Vietnam, etc. And the very near miss in the US in the 1930s. This evidence contains a hard lesson for the nineteenth century-style Social Darwinists all over the world: if you want to live, be nice. Share. Workers have to be paid enough to be able to care for their families. Otherwise, they will revolt. Living in misery, with daily starvation for themselves and their kids, they have nothing left to lose. Social Darwinism, left to its own ways, driven only by markets and their codes, will gradually tend more and more toward this exact picture. For whole societies, chaos, pain, blood, and death. And that description is not overly florid or dramatic. It’s just what the evidence shows.

Victorious North Vietnamese troops capture

Saigon, 1975

(credit: Wikipedia)

Experience in countries all over the world has shown that societies containing more compassion and social justice – unionization of workers, state-funded health care, etc. – can work, and do work, and ordinary folk all over the world today know this. They will not accept exploitation, bare subsistence living, and misery as their necessary parts in society anymore.

The

values code that guides society to its highest levels of efficiency is one that

balances courage with wisdom and freedom with compassion. Leaving love out of

our picture of human society is not just cruel; it’s stupid. As unregulated,

unrestrained capitalism just keeps doing its thing, manoeuvring for greater and

greater profits, the exploitation gets worse and worse until, eventually, it

costs its adherents their heads. Literally. This is becoming clearer and

clearer as we have more and more historical records to study and find patterns

in.

Teamsters’

union members vs. police, Minnesota, 1934

(credit:

Wikimedia Commons)

Now

let’s consider an example that shows how values can find equilibrium in a real democracy.

This example is relevant and useful here because it can be seen as a paradigm

of how sub-cultures of societies in the West, at their best, are guided by

their values as they interact in all areas of their lives, professional and

personal. (In English, we say our actions are informed by our values.)

Workers

and management in Western economies can be thought of as “social species”. A

captain of industry in the West today has times when he despises unions, but he

accepts that if workers are not paid a fair percentage of the company’s

earnings, they will work less and less efficiently. His best workers will leave

his firm to find other jobs. Other workers, fed up, will willfully sabotage the

company. He may find ways of retaliating, but he knows those will simply cause

the cycle to deepen and worsen. If the obstinacy on both sides becomes hardened

enough, violence is inevitable. If those who run the means of production –

farms, mines, factories, etc. – become more incorrigible in their attitudes,

society eventually breaks down into revolution. To prevent such chaos and

preserve his way of life, the smart CEO has ambition/drive/diligence (courage),

but also wisdom. A smart CEO works with, not against, his workers.

Thus, we

have learned, by trial and painful error, to aim for balance. For example,

workers in democracies have rights to safe working conditions and free

collective bargaining via their unions. Smart businesspeople negotiate with

unions, and contracts are arrived at by debate and compromise. In fact, some of

the smartest businesspersons in the West today are those specifically trained

in labour-management negotiations.

union leaders with Ford executives

(contract

signing 2007) (credit: Ford Motor Co., via Wikimedia Commons)

For

their part, most union leaders today know they have to respect a company’s

ability to pay. They ask for reasonable wages and benefits for their members,

but smart union bosses don’t push the employers to the brink of insolvency. To

do so would simply be irrational. Union leaders need courage and wisdom in

balance as well.

Furthermore,

most business leaders in the West have accepted that as long as prices go up,

workers will expect wages to go up accordingly. Ethical business leaders

make businesses more efficient by funding research and by efficient management,

not by union-busting. Attempts at strike breaking are viewed today as signs of

management incompetence. Overall, finding balance between all the parties

trying to get the work done is the key to making the whole economic system of

the nation vigorous.

And

clearly, the system is not random. It does not find a working balance by lucky

chance, nor by one individual's choice. Many parties, guided by their concepts

and values, interact, give a bit, demand a bit in return, and reach agreements

that are viable in the real world. Values drive behavior, and, in turn,

behavior must interface with reality. Values that mirror the forces of the

physical world are the ones that produce working compromises. Companies whose

workers and management strive to balance enthusiasm with judgement (courage and

wisdom) and innovation with respect (freedom and love) produce quality,

sensibly-priced goods and their firms thrive. Those that don't – don't.

Thus, in

the view of cultural evolution, two social species – management and labor –

stay in balance by following their cultural programming.

There

are also some even more nuanced ways of seeing balance in this labor-management

subsystem within our society. One truth is that while most smart business

leaders hope they can achieve a modest settlement with their workers, they also

hold values that make them secretly hope the rest of their society’s workers

will get generous new contracts. That will mean more disposable income in the

economy, money that workers – who, during their time off, are just consumers – can

spend on the smarter company’s goods and services.

The

corollary is that while workers in any company want generous rates of pay in

their new contracts, they don’t want to see too generous pay packets being

handed out in all the contracts signed in all sectors of their society. If

settlements in general are modest, workers know that goods will soon be cheaper

relative to their wages than those goods were just a few months ago.

If they

are honest, most workers will also admit that they want their company to

succeed. Their jobs depend on it. Some of the leaders of their company may seem

unsympathetic and unyielding, but smart workers know that managers who

scrutinize every line in their books, as long as they also know how to adapt to

innovations and to market their goods in creative ways, are the ones the

company needs if it is to stay in business and keep workers employed.

In

short, in the modern business world, smart business people don’t live by Social

Darwinism and smart workers don’t live by Marxism. Democracy in all its sectors

runs by extremely complex interactions, tensions, and balances of all parties

with all their concepts and values functioning vigorously.

A natural

balance: wolves closing in to kill bison

(credit: Doug

Smith, via Wikimedia Commons)

Over time, the wolf pack keeps the bison herd strong, and vice versa. Over time, management and union leaders, tough but smart, keep each other and their whole country economically and socially strong. The negotiating costs emotion, but it’s effect over the long term is to prevent violence. The uplifting thing to notice here is that in democracy, we have learned to find balances almost always by non-violent means. Firms go bankrupt sometimes. Unions cease to exist if some kinds of work are made obsolete by technology. But managers and workers do not have to kill one another to enable cultural evolution to happen. We can live and evolve peacefully under the rule of law.

This

discussion of the ways in which social evolution can be compared to genetic

evolution can be fruitfully pursued even further. Thus, the analogy between

memes and genes is not a metaphor. Meme variation and selection drives cultural

evolution as surely as genetic variation drives other species’ evolution.

Another

comparison between a meme that is found in many cultures and a set of

genetically programmed features in several species of the living world will

deepen our understanding of how cultural evolution works.

Prickly

pear cactus, USA

(credit: mark

byzewski, via Wikimedia Commons)

Cactus

flowers, Jordan (credit: Freedom's Falcon, via Wikimedia Commons)

In Biology, convergence is the term

for the phenomenon seen in species that are separated geographically, but that,

after eons of evolution, are using similar strategies for survival. Desert

plants of widely differing species, in widely separated deserts, have waxy

leaves. They also put off reproducing – maybe, for years – until that rare

desert rain arrives.

Native elder Agnes Pilgrim and grandchild

(credit: José Murilo, via Wikimedia)

Similarly,

nearly all human societies that have made it into the present age – with vastly

disparate cultures and from widespread geographic areas – respect, value, and

heed their elderly. Why? Because in pre-literate tribes, an old person was a

walking encyclopedia of the tribe’s knowledge – of hunts, crops, diseases,

etc.. What the old had stored in their heads could save lives, even save a

whole tribe. Thus, honoring one’s father and mother became a value in tribes

all over the world. Tribes that honored the elders grew and thrived. Ones that

didn’t …didn’t. This evidence demonstrates convergence in the cultural realm.

Indonesian and grandson (Uwe

Aranas, via Wikimedia Commons)

For even

more general reasons, wisdom is a core values in cultures everywhere, so common

that it’s seen as basic to human life. But I’ll stress again that it is not put

into us by our genetics. Respect for wisdom is socially programmed.

The

wisest lion in a pride is not necessarily its alpha leader. That position goes

to the strongest, and the wisest old cat can readily be pushed aside by a

strong young challenger. Humans, in their societies, have learned a better way.

There is

nothing in the genes of the human animal to predict that valuing wisdom will

occur in societies everywhere, as naturally as walking on two feet does.

Bipedal motion arises automatically out of our genetic design. But morés like,

for example, respecting elders don’t. Certain values are found in societies all

over the world because they work; they’ve proven over generations that they

make a human society more likely to survive and flourish. This is convergence

in social evolution. Our societies are analogues of cacti with waxy leaves.

Graphic

of fitness landscape concept (Randy Olson,

Wikimedia Commons)

Other

concepts in Biology also apply in analogous ways. One of the subtlest is

what evolutionary biologists call a fitness landscape, which is the

model from which the concept of cultural convergence derives.1 If

we draw a graph showing how two genetic traits, say size and coloring,

interact to give a size-color survival index for a given species in a given

environment, we can find the place on the graph where the two traits hit the

spot that yields the best survival odds for that species in that

environment.

Next, we

can plot a similar graph for three biological traits of a species in three

dimensions, with an x axis, a y axis, and

a z axis. The resulting picture would show in three dimensions

a theoretical landscape with ridges, peaks and valleys. The peaks indicate

where the best combination of coloring, size, and, let’s say, coat density lie

for that species’ survival in its environment.

Geneticists

speak of fitness landscapes of ten, fifty, and two hundred dimensions as if

what they are talking about is completely clear. No graph of any such landscape

could be pictured by the human mind, but with the mathematical models we have

now, and with computers to do the calculations, geneticists can predict what

niches in an emerging environment will contain which kinds of species and how

long it will take for species in that ecosystem to find balance.

The

concept of a fitness landscape – one that exists only in mathematical space –

can then be applied to the combinations of memes in human cultures,

combinations that produce morés and patterns of behavior in real people’s

lives. The concept of a meme – a basic unit of human thinking – is a tenuous

one, and it is still considered by some social scientists to be unproven and of

uncertain value. (see Dawkins’s “Selfish Genes and Selfish Memes,” in

Hofstadter and Dennett’s The Mind’s I for a basic explanation

of the meme concept.2) But for now, if we take the meme concept as a

given, the thinking enabled by it supports this book's thesis.

We can

construct, in imaginary, mathematical space, a fitness landscape for memes –

for basic concepts, in other words – that humans use to build systems of

beliefs about what the universe is made of and what forces drive and steer the

movements of the things in it, including us, the human, thinking things.

That

fitness landscape, that multi-dimensional graph of the ways of thinking

underlying a culture, will be very similar for all individuals in that culture.

I tend to reason my way to the same patterns of behavior as my parents lived

by. What I mean by words like red and round and sweet and edible is

very close to what other English speakers mean by these terms. So is what I

mean by plum and apple. I recognize the things these words name.

I like fruit. I eat it often.

My ideas

of beauty also roughly coincide with other Canadians’ ideas of beauty. Even our

definitions of abstract terms like good, wise, just,

and democracy roughly coincide. They enable us to communicate, work

in teams, and live in community. Usually. Fairly successfully, in fact. I am a

son of my culture.

Useful

concepts – that is, meme combinations that correspond to peaks on the fitness

landscape – are “found” by the people in a culture over generations of that

culture’s evolution because through trial and error, the concepts prove

effective in physical reality. They enable people who think with them to design

behavior patterns that get good results, and so, to survive and flourish.

No

single culture is ever the only combination of concepts or behavior patterns

that could work in a given environment. People of other cultures could use

their own concepts and morés to survive there. Human societies are varied, tough,

capable, and versatile, similar to the various species in a living ecosystem.

But any

society or tribe that settles in a given ecosystem will come to think with

memes, concepts, and values that enable the tribe to survive. For example,

people can learn to fish with hooks, nets, spears, or baskets, depending on

what materials are available in the region and what technologies are already

familiar to the people. But the odds are very good that if there are lots of

fish in a lake, then any tribe that settles next to it will learn to fish, by

one method or another.

Stilts

fishermen, Sri Lanka (Bernard Gagnon,

Wikimedia Commons)

Traditional

fish trap fishing, Vietnam (Petr Ruzicka, Wikimedia Commons)

Ice

fishing, Canada (credit: mattcatpurple, via Wikimedia Commons)

Bow

fishing, Philippines (James David Givens, Wikimedia Commons)

People

in varied cultures all over the world also establish markets in the middle of

their towns for commercial activities like the selling of fish, and they hire

police to patrol the market to stop thieves. Getting fish out of the water and

into human stomachs is healthy for tribes that learn to catch fish and set up

markets. They get stronger and out-multiply less vigorous neighboring

tribes.

Marketplaces,

policing, and currencies are efficient social constructs because they help

societies that create them to maximize the usefulness of what their citizens

produce; they allow venture capital to form and flow. If the people have no

currency yet, even surplus goods can work as barter capital, to flow, in a

timely way, to where it can do the most good. Fresh fish are a healthy source

of protein. Rotten fish benefit no one’s diet. Hence, marketplaces.

Some

large meme complexes we call values guide us toward forming

institutions that are advantageous for the tribe and especially for the

subgroups that believe most devoutly in those values. Some do not. Values

survive if they enable people who follow them to create behavior patterns that

work, behaviors that feed and shelter more people, and enable them to live and

work together in peace. The tribes that believe and practice these values

survive in greater numbers over the long haul of generations to pass the values

on to their young.

Learning a custom: Maori warrior

hongi-greeting American soldier

(credit: U.S.

Air Force photo/Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo, via Wikimedia Commons)

A

custom: traditional Indian Namaste greeting

(credit: Saptarshi

Biswas, via Wikimedia Commons)

It is

true that many differences between the cultures – the memes, concepts, and

morés of different societies – can be found.

But to

say, as some moral relativists do3, that cultures are

incommensurable – that they can never learn from each other or create

institutions for settling disputes between their tribes, and so get along – is

to abandon humanity to war for all time. Furthermore, that idea – that cultures

are incommensurable – simply isn’t true.

A

greeting custom: American handshake (Pres. Obama greets Pope Francis)

(credit: Tech. Sgt. Robert

Cloys, via Wikimedia Commons)

In the

first place, though there are differences, there are many similarities in our

various cultures. Some of the top peaks in the meme-scapes of all cultures

coincide. Everywhere on earth, people respect and value courage, wisdom, love,

and freedom. Different cultures adhere to moral values, and the patterns of

behavior that they lead to, in varying ways, degrees, and combinations. But the

areas of thinking we have in common far outweigh our differences. As Sting said

in the 1980s, “The Russians love their children too.” (A universal value.)

English poet-musician Sting (Gordon Sumner)

(credit: Helge Øverås, via Wikimedia

Commons)

In the second place, we can learn. We can learn to fish in four ways instead of just one. We can learn to speak several languages. We can learn to restrain violent impulses that cause men to beat women or each other or engage in war. We can learn to imprison rather than execute murderers. We can learn regular exercise and moderate eating habits. People from many tribes, across History, have done these things many times.

In the

third and most important place, we can educate the kids to do better than we do.

They can learn work as a way of life. Push themselves. Train their bodies and

minds. And they can learn to love their neighbors. Every day.

The

values discussed in this book – values that derive from the physical universe

in which we live – point us toward a society that will place ever greater

emphasis on self-discipline, good will, imagination, education, and citizenship.

Balance.

We can

make a society in a state of dynamic equilibrium, capable of responding effectively

to an ever-greater range of challenges, both short and long term. We can become

tougher and smarter, overall, than we are now. Without war.

Then we

can spread our species out to our destiny – the stars. The potential is there;

all it needs in order to be made real is us. Our grand destiny is calling to

each of us now, asking: How much character do you have?

It is

true that when it comes to our values, morés, and patterns of behavior, we tend

to change slowly and grudgingly. But we can change. Thus, we could learn a code

and a mode of cultural evolution that is vigorous, but not militaristic.

Only

certain values, ones derived from our best world view – that is, Science – will

be rational ones to write into that code. To guide humanity to greater health

and vigor in the future. We all must survive in this same physical universe. It

is only reasonable for us to seek out and follow the values that Reason says

will give us the best odds of surviving in that universe over the long haul.

The

courage-wisdom meme complex, along with the behavior patterns it entails, is our

long-term response to entropy; the freedom-love meme complex is our long-term

response to quantum uncertainty. The optimal balance of them all is

called virtue or the Tao. The Way. It is always

shifting. In this nuclear-armed, global-warming era, we must see the shifts and

respond wisely. Or die.

Statue of

Lao Tzu (credit: Tom@HK, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Tao

Te Ching says: “The Tao that can be spoken is not the Tao.” Lao Tsu was telling

his disciples never to feel confident that they had life figured out or feel complacent

about their capacity to handle its challenges. Complacency is the harbinger of

disaster. The way of all ways, the Tao, is always shifting. To live as

individuals, but far more importantly as nations, we must stay alert,

resourceful, nimble, and sharp while remaining true to our largest values, the

ones that we can see match reality. A fine balance. Grace. The Tao.

Our most

general basic values are not tied to how we fish or cut our hair or talk or

dress or make bread. They are far more pervasive and general than that. But

they are found in all cultures in varying degrees, combinations, and styles

because they work. They are our tested, tried, and true best guides to where

the shifting path of long-term survival lies. Our basic values will apply even

on a planet to which we must bring our water because the planet is so dry.

So what do all these analogies between the biological and cultural modes of evolution tell us? Non-human species are programmed mostly by their genes to behave in ways that are well-suited to life in their environments. Species adjust to changes in their environments, mostly, by testing variations of their gene codes in the physical world and keeping the variations that work. Evolution.

Human

tribes, on the other hand, survive and adapt almost entirely by cultural

variation and testing. This chapter’s analogy between genetic evolution and

cultural evolution helps us to understand cultural evolution more deeply

because the cultural mode mirrors the genetic one in so many ways.

And to close this chapter, I need also to underline

the most important way in which memes can be compared to genes and social

species to biological species.

A society is an ecosystem. It can contain

millions of individuals and hundreds of “social species”, all of which

sometimes cooperate and sometimes compete, and switch from one role to the

other even with the same neighbors, as evolution advances. Entrepreneurs.

Professional doctors, lawyers, and engineers. Artists. Farmers. Tradesmen.

Academics. Soldiers. These and many others can be seen as “species” within the social

ecosystem. To those who seek a single, prescriptive set of beliefs and morés

for all members of their tribe to live by, I will repeat that such thinking is,

in the first place, a vestige of tribalism that we can no longer tolerate. In

the past, it set tribe against tribe. Out of the wars that ensued, yes, our

species got stronger. But today, either that way is done or we are. Our weapons

have gotten too big, our climate problems, planet-threatening. Either, we take

over our own evolution – rationally – or we die. It’s that simple.

In the second place, such thinking just is not

consistent with what we know from Biology about how ecosystems work. A society,

like any living ecosystem, to stay healthy, does better and better the more

diversity it contains. Then, it can adjust its internal balances and

interactions in many different ways, adapt to changes in its environment, and

still remain stable and vigorous. As biodiversity is good for an ecosystem, cultural

diversity is good for a human society, as long as citizens do not let themselves

fall into mutually hostile factions. Which means, as long as they love each

other, they will discover or devise ways to make their social ecosystem work.

This is the purpose for which our species evolved the intelligence we now have.

We are designed by evolution to take over managing evolution: the evolution of

our species, our fellow species, and the biosphere of Earth. Then, to carry

this incredible miracle to the stars.

Tolerance and diversity are the most telling hallmarks

of freedom. Therefore, at least some daily anxiety comes with the human

condition, especially as it is experienced in the most vigorous of societies –

namely democracies. We are genetically hard-wired to feel nervous when we encounter

other humans who look, talk, and act different from the ways we grew up with.

That is why war comes so easily to us.

But Reason is the gift of our more recent evolution,

and it tells us that evidence shows

socio-diversity is good for us in the long haul. So? Get used to it. Your

neighbor’s ways that you find strange serve a higher purpose: in this real,

physical world, those ways may one day save your life.

Notes

1. “Convergent

Evolution,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Accessed April

30, 2015.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convergent_evolution.

2.

Richard Dawkins, “Selfish Genes and Selfish Memes,” in Douglas R. Hofstadter

and Daniel C. Dennett, The Mind’s I: Fantasies and Reflections on Self

and Soul (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1981), pp. 123–144.

3.

Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (London, UK: Bloomsbury

Academic, 2013), p. 78.

No comments:

Post a Comment

What are your thoughts now? Comment and I will reply. I promise.